Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Hans Singer * 1921

Hasselbrookstraße 127 a (Wandsbek, Eilbek)

1941 Minsk

ermordet

further stumbling stones in Hasselbrookstraße 127 a:

Rosa Singer

Rosa Singer, née Wolff, born on 10 Feb. 1876 in Altona, deported on 18 Nov. 1941 to Minsk

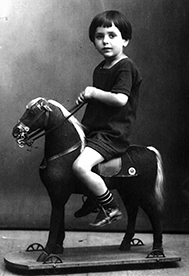

Hans Singer, born on 23 May 1921 in Hamburg, deported on 8 Nov. 1941 to Minsk

Hasselbrookstrasse 127a

Rosa Singer, née Wolff, came from a Jewish family in Altona. Her parents were the cigar worker Levy Michel Wolff and Eva, née Levin. Rosa Singer had one brother. In 1900, she married Fritz Singer, born in Leipzig in 1881. The marriage produced two children, daughter Margarete, born in 1912, and son Hans, born on 1921.

Fritz Singer was a merchant. He represented the Sächsisches Warenlager Company in his residential and business premises at Grosse Roosenstrasse 88 (today Paul-Roosenstrasse) in Altona. The 1911 Altona directory contains for the first time an entry that refers to Fritz Singer. In about 1915, the Singer family moved into an apartment located at the neighboring address of Grosse Roosenstrasse 73. By 1920/1921, the cooperation with the Sächsisches Warenlager Company had apparently ended. From 1922 onward, Fritz Singer’s company, specializing in slippers, did business under the name of "Fritz Singer Pantoffelhandlung” for two years, then as "Fritz Singer Wollwaren,” trading in woolen goods. Fritz Singer took his own life on 1 Feb. 1929, at the age of 48. He died in the Altona municipal hospital. The reasons for his suicide are not documented.

Probably Rosa Singer attempted to continue managing the company for a while. However, she soon worked in the business of Emil Oestreicher, who operated a fruit, vegetable and food retail store, located not far from her residential building at Grosse Roosenstrasse 96, since 1930. Rosa Singer invested a share of 5,000 RM (reichsmark) in his enterprise. Margarete Singer, her oldest daughter, was also employed there. She won Emil Oestreicher’s affection. The two got engaged in 1931.

Emil Oestreicher was a Protestant, came from a Social Democratic family, and rejected Nazism like his two brothers. After giving up his store in Altona in 1932, he was, jointly with his brothers Otto and Wilhelm, the co-owner of additional retail stores and a wholesale company on, among other places, Hamburger Strasse and Lübecker Strasse in neighboring Hamburg. In 1934, he was drawn back to Altona again. In the house of the Singer family at Grosse Roosenstrasse 73, Emil Oestreicher and Margarete Singer jointly opened a grocery store in the spring of 1934, a business employing a staff of one or two on a regular basis as well as temporary workers. From her mother, Margarete Singer had received 6,000 RM as a contribution of capital to the joint enterprise. A few months later, they sold their store in Altona and in the same year – while still bride and groom – opened a fruit, vegetable, and coal store at Grindelallee 91 in Hamburg. For the most part, their customers were local Jewish residents.

Although Emil Oestreicher was not Jewish, he too became the target of massive hostilities that culminated, for the time being, in Nov. 1934 when all tires of his delivery truck were slashed. Placed in the driver’s cab was a piece of paper that read, "You just wait, you Jew pig, we will soon smash your store.” Physical attacks alternated with massive threats. During the main shopping period in the early evening, repeatedly a group of six to eight underage boys and girls, identifiable by their garb as members of the Deutsches Jungvolk [literally, "German Young People,” i.e., the section of the Hitler Youth for adolescents aged 10 to 14], showed up, threatening customers with aggressive chants. In December, the store was demolished by large rocks thrown through the glass doors. At night, the shop windows were smeared with anti-Jewish slogans in red paint. In the course of these attacks, Emil Oestreicher sustained kicks and serious injuries. Margarete’s 13-year-old brother Hans had to witness the discrimination and violent measures. Emil Oestreicher defended himself, beating up one of the graffiti culprits several times. This earned him the threat at the Stadthaus, the headquarters of the State Police (from early 1936, Secret State Police, i.e., Gestapo) in Hamburg, that it was over with the Jews for good and that for him personally, the clock had struck "five minutes to midnight.” In Jan. 1935, the orders followed that he was to close the business within 14 days and sell the stock on hand immediately.

The discrimination and threats did not prevent Emil Oestreicher and Margarete Singer from getting married in May 1935. Between 1935 and 1939, the couple had three children.

Emil Oestreicher continued the itinerant grocery trade in external markets and managed to maintain it all the way until 1937. However, in this context, too, threats and boycotts, particularly directed against his wife and daughter, became more frequent, forcing him to cease business activities eventually. On the orders of the authorities, Emil Oestreicher had to turn in the business license, which constituted the authorization for his trading, in late 1937/early 1938. From 1940 onward, he was employed as a brick transport worker.

Over the course of time, the revenues of the Oestreicher family had declined to such an extent that they depended on contributions by Margarete Oestreicher’s mother. Rosa Singer had – according to son-in-law Emil Oestreicher – been given 150,000 RM from her brother, who lived in London. However, when only a portion of the interest from the assets was paid out, she had to stop supporting her daughter’s family. Starting in 1940, she – actually a wealthy woman – received only 120 RM a month in family allowance, later a mere 80 RM.

In 1936, Rosa Singer gave up her apartment at Grosse Roosenstrasse 73 and subsequently lived on Wandsbeker Chaussee 158. Two other places of residency as a subtenant followed, at first with the Förster family at Hasselbrookstrasse 53 and then with the language teacher H. Dancker at Ritterstrasse 65. In about 1939/1940, Rosa Singer moved in with her son, the printer Hans Singer, who had already had an apartment at Hasselbrookstrasse 127a earlier.

All of this makes it apparent that Rosa Singer, her son Hans, as well as her daughter Margarete and her son-in-law Emil Oestreicher eked out a very modest existence in the ensuing period. On 8 Nov. 1941, Hans Singer was deported to the Minsk Ghetto. Rosa Singer followed in the second deportation from Hamburg to Minsk on 18 Nov. 1941. There was no further sign of life at all from them.

Immediately upon the deportation, the Housing Maintenance Department (Wohnungspflegeamt) compiled lists containing the "Jews’ apartments being vacated” which were to be re-occupied by "Aryan” tenants.

The Hamburgische Electricitäts-Werke AG, the local electricity company, sent a letter dated 28 Mar. 1942 to the "Administrative Office for Jewish Assets” ("Verwaltungsstelle für Judenvermögen”) with the Hamburg-Dammtor Tax and Revenue Authority demanding reimbursement of 6.24 RM for "electricity used […]” by Rosa Singer "until her move.”

When Rosa and Hans Singer were deported to Minsk in Nov. 1941, Rosa’s son-in-law, Emil Oestreicher was already on military duty. He had been drafted in June 1940 and remained a soldier until the end of the war. From Feb. 1942 onward, he was in German military detention in Belgium. He was accused of "undermining military strength” ("Wehrkraftzersetzung”) because he had given goods from military stocks to German emigrants and Belgian Jews.

Rosa Singer’s daughter, Margarete, and their three daughters had to fight their way through this on their own. In 1943, they were bombed out and left Hamburg for a few months. Subsequently, Margarete Oestreicher lived illegally with her children by keeping silent on her Jewish descent. Back in Hamburg, she found accommodation with her children starting in Oct. 1943 in Hamburg-Rahlstedt, in a shed at the rear part of the agricultural property owned by Marie and Adolf Pimber, at Mellenbergstrasse 74. This shed Emil Oestreicher had built with foresight. The property owner took in the Oestreicher family "because […] Mr. Oestreicher, together with his wife, was known to us as an opponent of Nazism, and also because Margarete Oestreicher was ill and in need of care when she moved here.” Though Margarete Oestreicher was registered with the local administration office (Ortsamt) in charge, she did not collect any food ration coupons as that could have led to her discovery. The hunger was alleviated only temporarily by the food parcels Emil Oestreicher sent them on an irregular basis. Life in Rahlstedt was filled with constant fear. When there was danger, the mother and daughters hid in an earth bunker on the property. Margarete Oestreicher and her three daughters had to persevere through this situation until the end of the war. They survived, just like their husband and father.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: January 2019

© Ingo Wille

Quellen: 1; 4; 5; 8; 9; AB; StaH 314-15 OFP Oberfinanzpräsident 26 (Wohnungspflegeamt), 29 (HEW); 332-5 Standesämter 6189-442/1876, 5374-226/1929; StaH 351-11 Amt für Wiedergutmachung 24941; StaH 522-1 Jüdische Gemeinden 922 e (Deportationslisten), Bde. 2 u. 3; Hoppe, Ulrike, "... und nicht zuletzt Ihre stille Courage", S. 96ff.

Zur Nummerierung häufig genutzter Quellen siehe Link "Recherche und Quellen".