Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

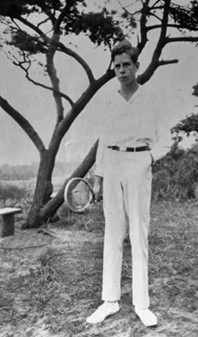

Hans Vincent Scharlach * 1919

Fontenay 10 (Eimsbüttel, Rotherbaum)

KZ Neuengamme

gehenkt am 23.4.1945

Hans Vincent ("Hannes”) Scharlach, born on 27 June 1919 in Hamburg, arrested on 30 Dec. 1944 for "behavior detrimental to the state,” imprisoned in the Fuhlsbüttel police prison, transferred to the Neuengamme concentration camp on 20 Apr. 1945, murdered there between 22 and 24 Apr. 1945

Fontenay 10

On 20 Apr. 1945, a few days before British troops entered Hamburg, 71 Gestapo prisoners, 58 men and 13 women, were taken from the Fuhlsbüttel police prison to the Neuengamme concentration camp, where they were murdered during the nights of 22 and 24 April. The Gestapo regarded them as "highly dangerous elements” that "had to be eliminated at all costs.” In the camp bunker, they were strangled, torn to shreds by hand grenades, or killed by shots to the head. Among them was Hans Vincent ("Hannes”) Scharlach, 25 years of age. (On these events, see also www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de > Glossar/KZ Neuengamme [in German] and ibid. > Dokumentation/Die letzten Toten [in German]).

What put him, the young man from upper class Hamburg’s circles, on the Gestapo’s death list is still unclear. In the last days of rule, the Hamburg headquarters of the Gestapo almost completely destroyed its documents, and the name Hans Vincent Scharlach does not appear in the files on the legal proceedings against the Hamburg Nazi perpetrators after the war before the British Military Court in the Curio-Haus (Neuengamme Trial, in 1946; Fuhlsbüttel Trial, in 1947) and the Hamburg Regional Court [Landgericht] (Gestapo Trial, in 1949). The fact that he was among those deported to Neuengamme, however, was confirmed by police sergeant (Wachtmeister) Heinrich Borgert of Fuhlsbüttel Station A2, where Hans Vincent was imprisoned, before the committee of former political prisoners in 1945.

Hans Vincent Scharlach was born on 27 June 1919 in Hamburg. His father was Otto Julius Gideon Scharlach (20 Feb. 1876 to 5 Dec. 1957), a lawyer with a doctorate in law, an attorney for maritime law, and a partner in the respected law firm of Stegemann, Sieveking, and Lutteroth (founded in 1840). The mother, Magdalena Scharlach (8 Feb. 1891 to 21 Oct. 1970), née Baur, came from the Baur family, who had been living in Altona since 1723, later in Blankenese, and who had achieved wealth and social standing through investments in shipping companies, insurance corporations, and banks, among other things. Besides Hans Vincent, the marriage produced the siblings Joachim Friedrich Julius (18 June 1916 to 19 Aug. 1971) and Anneke (1918 to 2003). The Scharlach family lived in the Fontenay, in one of the villas on the grounds of the John Fontenay Foundation between Alsterufer and Mittelweg. Today, The Fontenay Hotel occupies part of this area.

Hans Vincent’s grandfather Julius Scharlach (born on 14 Feb. 1842 in Bodenwerder, died on 28 Mar. 1908 in Hamburg), a lawyer specializing in maritime law and a shipbroker, was one of the most active colonial politicians and entrepreneurs of the German imperial era. He represented a decidedly German-national attitude, which he propagated, including as chairman of the German School Association for the Preservation of Germanness Abroad (Deutscher Schulverein zur Erhaltung des Deutschtums im Ausland). He was friends with Carl Peters (1856–1918) and General Lothar von Trotha (1848–1920), the colonial masters of German East Africa (Tanzania, Burundi) and German Southwest Africa (Namibia). His sphere of activity as a politician and investor extended from China via Africa to Brazil.

Julius Scharlach’s father, the great-grandfather of Hans Vincent, Louis Scharlach, had been a merchant in Bodenwerder near Hildesheim/Lower Saxony. He, as well as his wife Rosa, née Ehrenberg, were of the Jewish faith. However, the following generations gradually gave up Judaism. Already Julius, the colonial politician, as well as his wife Bettina, née Speyer, were temporarily registered in civil status books as "without religious creed” ("ohne Religion”), then joined the Calvinist (Reformed) Church. Julius even temporarily belonged to the advisory board of the Hamburg Reformed Church.

Hans Vincent’s father, Otto Julius Gideon, was already baptized a Protestant as a child. The family of origin of his wife Magdalena, the Baur family, had always been Protestant. In short, the Scharlachs had fully assimilated and did not differ in lifestyle from others in their social class. Hans Vincent and his siblings had left Judaism behind them.

Everything changed with the so-called racial legislation of the Nazi state, passed in Aug. 1935 ("Nuremberg Laws”): Otto Julius Gideon became a man of lesser rights, a "full Jew” ("Volljude”). The children Hans Vincent, Joachim Friedrich, and Anneke were suddenly "half-Jews” ("Halbjuden”), "Jewish crossbreeds of the first degree” ("Mischlinge 1. Grades”), and they had to reckon with adverse effects from then on. Hans Vincent was 16 years old by this time. Because of the racist persecution policy of the Nazi state, Otto Julius Scharlach, Hans Vincent’s father, lost his license to practice as a lawyer in Nov. 1938. He feared worse and fled to Switzerland in June 1939. According to Swiss law, he was unable to exercise his profession because racist persecution in Germany was not considered grounds for asylum in the Swiss Confederation. As a writer, on the other hand, he earned some income, with friends and relatives also helping.

Hans Vincent, as tradition from his family and friends has it, was an athletic, lively, and enterprising young man with a big mouth. From childhood, he played hockey and tennis in the Club an der Alster (DCadA), whose tennis section his mother had co-founded. He acquired the reputation of a crack with elegant and imaginative play. Tennis players from various Hamburg clubs were looking for a match with him. In addition, he was a good skater, in winter a regular on the ice rink in Planten und Blomen, a park area in central Hamburg. There he liked to hook up with the girls, and in quite daredevil ways at that. As late as the year 2003, Hanna Brinkmann (born in 1924) was able to recite, impromptu during a broadcast on NDR radio, the poem that Hans Vincent had put in rhymes for her and handed over to her with verve on the ice rink. (See below) But the happiness conjured up poetically came to nothing. Hanna’s parents, who got wind of the flirting, stepped in. That was in the winter of 1936/37; Hans Vincent was 17, Hanna 13.

After 1935, the disappointments that depressed Hans Vincent also increased in other respects:

On 4 Apr. 1935, the club had committed itself in its new constitution to the "National Socialist ideology, völkische ideas, and physical training of youth along the lines of the Nazi state.” Did the "Jewish crossbreed of the first degree” fit into this scheme? How did he do at the "Club”?

The association has remained silent on these questions to this day and has avoided providing information even more than 70 years after the end of the Nazi era. In the chronicle of DCadA’s 90th anniversary (in 2009), which also gives insight into the composition of the first men’s tennis team, the name H. Scharlach appears for the last time in 1936/37. A photo from the winter of 1940 shows Hans Vincent with the leisure soccer team made up of club members. This team was not an official part of the club. A member of the association said after the war that Hans Vincent had not been excluded. Others stated that he had automatically lost his junior status at the age of 19, i.e., in 1938, and thus his DCadA membership. They admitted that they had withdrawn more and more from him, with whom they had once been so fond of competing, though without any discussion of the matter in the club. The subject was off-limits. In the aforementioned chronicle of the association from 2009, it says tersely about the years from 1939 to 1945: "The Second World War left its mark. The lists of fallen club members grew longer and longer, and a depressing time began.” (p. 47).

That members of the DCadA were persecuted, expelled, and murdered because of their Jewish origin is not mentioned. (In 2019, the Club an der Alster will have its 100th anniversary and a commemorative publication will probably be published.)

Moreover, in Hans Vincent’s school career, some things are very unclear, even irritating. Since Easter 1926, he initially attended, like his brother Joachim before him, the Hamburg private Bertram school, which was praised as progressive. After the fourth grade, at Easter of 1930, he changed to the traditional and strict Academic School of the Johanneum ("Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums,” founded in 1529 in the course of the Reformation in Hamburg), which his father had also attended. After only four years, however, he left school in Feb. 1934, at the end of the eighth grade (Untertertia). In spite of grades in the range of twos and threes (approx. Bs and Cs), the departure was suggested to him ("Consilium abeundi”). Reason given was that his conduct had allegedly been poor throughout. Strangely enough, in the performance sheet kept at the school at the end of the school year, "initially four [D], now three [C]” is entered under the heading "conduct.” So Hans Vincent’s behavior had improved, the admonition had had an effect.

Hans Vincent changed to the new school year in the 3rd class (Obertertia; in today’s way of counting, grade 9) of the Wilhelm-Gymnasium (WG) during the spring of 1935. He was almost 15 years old by then. Only one year later, something strange happened again: He was expelled from school. Neither his student card, which has been preserved, nor the report card gives any reason. Was it that Hans Vincent had behaved too badly again? Was it that his achievements did not meet the requirements of the demanding high school? The diploma indicates something completely different: Conduct good, diligence good, performance results average overall.

The matter is puzzling: Why is a student expelled from the institution and at the same time issued an acceptable report card? The idea immediately suggests itself that Hannes was expelled for racist reasons. No evidence of that exists. So-called "crossbreeds” ("Mischlinge”) were officially banned from attending the secondary school only in 1942 with the corresponding decree of the Reich Education Ministry (Reichserziehungsministerium) dated 2 July 1942 (unless, as a law of 1933 prescribed, a school had more than 5 percent Jewish and "half-Jewish” students). In addition, despite the school’s adaptation to the Nazi regime with flag ceremonies, lane formation during Hitler’s visits to Hamburg, and heroic heroes’ memorial services in the auditorium, some Jewish schoolchildren at the Wilhelm-Gymnasium passed their high school graduation exams (Abitur) in the 1930s, and they later remembered their school days favorably. The reason for Hans Vincent’s expulsion remains unclear.

At this point, Hans Vincent Scharlach started a commercial apprenticeship at the Otto Gierth u. Co. import and export company, a prospering company on Ballindamm (at that time: Alsterdamm) and supplier for the military, especially the navy. At Gierth, acquitting himself well, he was employed permanently after the end of his apprenticeship. In 1943, he was promoted to purchasing manager. He traveled a lot, even to occupied foreign countries.

One of these trips, to the Netherlands in 1944, caused him, 25 years old by then, some trouble, which possibly contributed to his subsequent arrest by the Gestapo: For an acquaintance, he procured a 500-gram gold bar in Amsterdam, brought it to Hamburg undeclared and handed it over to the client. However, the man he did not pay. A dispute arose and Hans Vincent was subsequently prosecuted before the District Court (Amtsgericht) for a foreign currency offense. On 9 Nov. 1944, he was sentenced to two months in prison for "unauthorized purchase and sale of gold at excessive prices.”

However, both the criminal investigation department and the judge had such a good impression of Hans Vincent’s personality that he initially stayed out of prison. He was supposed to start serving his sentence only upon being ordered to do so. Before this happened, though, the Gestapo appeared at his workplace on 30 Dec. 1944 and arrested him for "behavior detrimental to the state.” This charge, as well as that of "preparation to high treason” (VzH – "Vorbereitung zum Hochverrat”), was a common accusation of the Gestapo when it intended to take action against someone. Hans Vincent Scharlach was taken to the Fuhlsbüttel police prison. A few days later, his brother Joachim was arrested by the Gestapo on the same charges and detained in Fuhlsbüttel.

Both arrests had been carried out by the Gestapo officer Henry Helms, Kriminalsekretär [a rank equivalent to detective sergeant or master sergeant] at the Office IV A specializing in "Communism and Marxism.” But neither Hans Vincent nor Joachim had ever had anything to do with Communism or Marxism; according to statements from the family, that seems certain.

When the Fuhlsbüttel police prison was evacuated on 12 Apr. 1945, Joachim was sent to the Kiel-Hassee labor camp. However, Hans Vincent and 70 other police prisoners were taken to the Neuengamme concentration camp on 20 April, where they were to be murdered.

Why had he been put on the liquidation list though? One can only venture guesses, as there is no evidence. The Gestapo man Helms was considered a fanatical anti-Semite even by his colleagues. Several of the victims of the massacre between 22 and 24 Apr. 1945 in the Neuengamme arrest bunker were so-called "half-Jews,” and it is puzzling what else could have turned them into "dangerous elements to be eliminated at all costs” (e.g., Senta Dohme, Heinrich Bachert, Bernhard Rosenstein; see their biographies at www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de).

However, why not his brother Joachim, too? Apart from the fact that the Gestapo by no means always worked as consistently and technically flawlessly as is often assumed, there could be a particular reason: Henry Helms, who was known in the Gestapo for being restless on a prey hunt, may have tracked down two points in Hans Vincent’s biography that to him in his private "final solution” program justified the elimination of the "half Jew”: the foreign currency offense and a reference several years before to contacts with the Hamburg Swing Youth (Swing-Jugend). (Strangely enough, according to the memorandum of the Hamburg District Court dated 8 Nov. 1945, the documents on Hans Vincent Scharlach’s criminal proceedings 11Js W 4692/43 "cannot be located, despite all search efforts”).

In the Swing Youth (or Swing Kids), young people had come together casually, mostly high school students from upscale liberal-oriented bourgeois circles, who agreed in their rejection of the Hitler Youth and in their soft spot for jazz, blues, and swing, and the casual way of Anglo-American manners. They met in certain cafés, bars or even privately at home, where they then presented their forbidden record treasures. The Gestapo persecuted them as "subverters of the people,” expelled them from school, and put them in juvenile penal camps and concentration camps. Their music was considered the "weapon of Judaism and Americanism.” An important meeting point for the Swing Youth in Hamburg was the ice rink of Planten und Blomen, where Hans Vincent liked to go. The years from 1940 to 1942 are regarded as the heyday of the Swing Youth. At the age of 21, Hans Vincent was actually well over the average age of the Swing Kids, but relations with them are quite possible. There is also a hint from Hamburg swing boy Hans Engel, who mentioned in 1989 that Hans Vincent Scharlach had been murdered because of his contacts to the swing scene and as a "half-Jew.” In this context, Engel also mentions the "murder” of the Swing boy Kurt Hirschfeld (born in 1922), who died on 28 Jan. 1945 in the Neuengamme concentration camp, due to diphtheria according to official information at the time. Hirschfeld was also a "Jewish crossbreed of the first degree.” (See the corresponding biography on www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de)

Joachim, Hans Vincent Bruder, survived the Kiel-Hassee "work education” camp and the Nazi period. After the end of the war, he became a successful businessman, especially in trade between the Federal Republic of Germany and Brazil. On 19 Aug. 1971, he also died violently: Gangsters from the Hamburg hood shot him in his house on Blumenau during an unsuccessful blackmail attempt.

The parents, Otto and Magdalena Scharlach, died in 1957 and 1970, respectively.

Hanna, du bist des Abends mein letzter Gedanke

und wenn ich des Morgens wieder erwache.

Oh, dass meine Liebe niemals schwanke,

dass deine mich ewig glücklich mache!

Liebst du mich schon lange,

dann verschließ dich mir länger nicht!

Lass uns genießen Wang an Wange

das Glück, worauf ich ganz erpicht!

Hanna, you are my last thought in the evening

and when I wake up in the morning.

Oh, that my love may never falter,

that yours may make me happy forever!

If you’ve loved me for a long time,

then don’t hide your feelings from me any longer!

Let’s enjoy, cheek to cheek,

the happiness that I crave!

Accompanying text: Poem that Hans Vincent Scharlach wrote for Hanna Brinkmann in the winter of 1936/37 and which she recited off the cuff during a radio broadcast in 2003.

(Source: NDR)

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: June 2020

© Johannes Grossmann

Quellen: Staatsarchiv Hamburg (StaH) 351-11_ 43144 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung/Hans Vincent Scharlach); StaH 351-11_13032 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung/Magdalena Scharlach); StaH 351-11_41479 (Joachim Scharlach); StaH 361-2VI_353 (Zulassungsbedingungen für den Schulbesuch durch Juden und "jüdische Mischlinge (1937–1944); StaH 361-2VI_354 (Gutachten über schulische Leistungen "jüdischer Mischlinge" (1945); StaH 361-2VI_990 ("Von der Schule verwiesene oder an eine andere Schule strafversetzte Schüler/ sog. Swing-Jugend, 1941-1942"); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter Hamburg)_8610, StA Blankenese, Urkunde 456, Heiratsurkunde Julius und Margarethe Emilie Scharlach; StaH 332-5_5747, StA Blankenese, Urkunde 29, Heiratsurkunde Otto Julius und Magdalena Scharlach, 1915; StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen) K 4883 (Hans Vincent Scharlach, 1943); StaH 731-8_A769 (Julius Scharlach); StaH 362-2/30_677 (Wilhelm-Gymnasium), Band 2 (Abgangszeugnisse) und _675 Band 10 (Reifeprüfungszeugnisse); StaH 213-11_2694/56 (Landgericht HH, Gestapo-Prozess); Bibliothek KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme, Neuengamme-Prozess (Curiohaus), Protokoll, hrsgg. vom Freundeskreis der Gedenkstätte, Hamburg 1969; Archiv der Gelehrten-Schule des Johanneums Hamburg: Schülerkarte Hans Vincent Scharlach, Sign. 9740 (1934); Schüleralbum 1921-1951, Sign. FXXV4; Zu- und Abgangsliste 1927–1934, Sign. FXXa; Rangordnungslisten, Sign.FIV; Übersicht über die Leistungen, Sign. FIV; Akte "Schulzucht III/Einzelnes 1928–1950", Sign. FIIIb.4; Archiv des Wilhelm-Gymnasiums, Schülerkarte Hans Vincent Scharlach, Album-Nr. 5353 (1936); Amtsgericht Hamburg, Vereinsregister, 69 VR, Band 34 Nr. 1753 Band 1 (Der Club an der Alster); Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Sign. Y572: Nachrichten/ Der Club an der Alster Jahrgänge 12/1937 und 13/1938; Der Club an der Alster, Hamburg: Chronik 1995–2009; Hamburger Adressbücher 1920–1945; Wilhelm-Gymnasium Hamburg 1881: Eine Dokumentation über 100 Jahre Wilhelm-Gymnasium, Hamburg 1981; Auskünfte Dr. Thorsten Todsen, Hamburg, Februar und November 2018; NDR Abendjournal Spezial auf 90,3, 12.7.2003: "Ein Jahr Stolpersteine in Hamburg"; Auskünfte Ines Domeyer, Archiv Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums, Sept. 2018; Auskünfte Dr. Lutz von Meyerinck, Stiftung John Fontenay´s Testament, Hamburg, 29.08.18; Auskünfte Michael Kater, Toronto, E-Mails vom 26.7. und 28.7.2018; Auskünfte Sybille Baumbach, DokuSearch, Hamburg, E-Mail vom 15.10.2018; Hamburger Abendblatt, 20.2.1952 (Otto Julius Scharlach); Johannes Grossmann, Die letzten Toten von Neuengamme, Hamburger Abendblatt Magazin, Nr. 14/2015, siehe auch www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de; Kater, Michael H.: Gewagtes Spiel/ Jazz im Nationalsozialismus, Köln, 1.A. 1995; Kater, Michael H.: Forbidden Fruit? Jazz in the Third Empire, American Historical Review, Band 94, 1989/1, Seiten 11–43; Meyer, Beate: "Jüdische Mischlinge". Rassenpolitik und Verfolgungserfahrung 1933–1945, Hamburg 1999, besonders S. 249ff. ("‚Mischlinge‘ als Opfer von Zwangsmaßnahmen"); Morisse, Heiko: Ausgrenzung und Verfolgung der Hamburger jüdischen Juristen im Nationalsozialismus, Band 1: Rechtsanwälte, Göttingen 2013; Pohl, Rainer: "Swingend wollen wir marschieren", in: Heilen und Vernichten im Mustergau Hamburg/ Bevölkerungs- und Gesundheitspolitik im Dritten Reich, hrsg. von Ebbinghaus, Roth u.a., S. 96ff., Hamburg 1984; Pohl, Rainer: "Das gesunde Volksempfinden ist gegen Dad und Jo"/

Zur Verfolgung der Hamburger ‚Swing-Jugend‘ im Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Verachtet, Verfolgt, Vernichtet, hrsgg. von der Projektgruppe für die vergessenen Opfer des NS-Regimes in Hamburg e.V., S. 14ff., Hamburg 1986; Storjohann, Uwe: Hauptsache: Überleben/Eine Jugend im Krieg 1936–1945, Hamburg 1993; Lust, Gunter: "The Flat Foot Floogee…treudeutsch, treudeutsch"/

Erlebnisse eines Hamburger Swing-Heinis 1936 bis 1966, Hamburg 1992.