Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Karl Ziemssen * 1903

Ipernweg 11 (Hamburg-Nord, Fuhlsbüttel)

HIER WOHNTE

KARL ZIEMSSEN

JG. 1903

IM WIDERSTAND

MEHRFACH VERHAFTET

ZULETZT 1941

BUCHENWALD

1942 GROSS ROSEN

ERMORDET

Carl Ziemssen, born 13.9.1903 in Hamburg, concentration camp Fuhlsbüttel and concentration camp Buchenwald, murdered 4.10.1942 in concentration camp Groß Rosen

Ipernweg 11

There is a retirement home in the Essener Straße neighborhood in Langenhorn. There I met Edgar Ziemssen in 2009. Edgar moves around in a wheelchair and his speech is a bit sluggish. But his wife Marlies helps him as much as she can. A sympathetic couple. I learn from Edgar that his father was killed in the concentration camp; the last time he saw him was when he was seven years old.

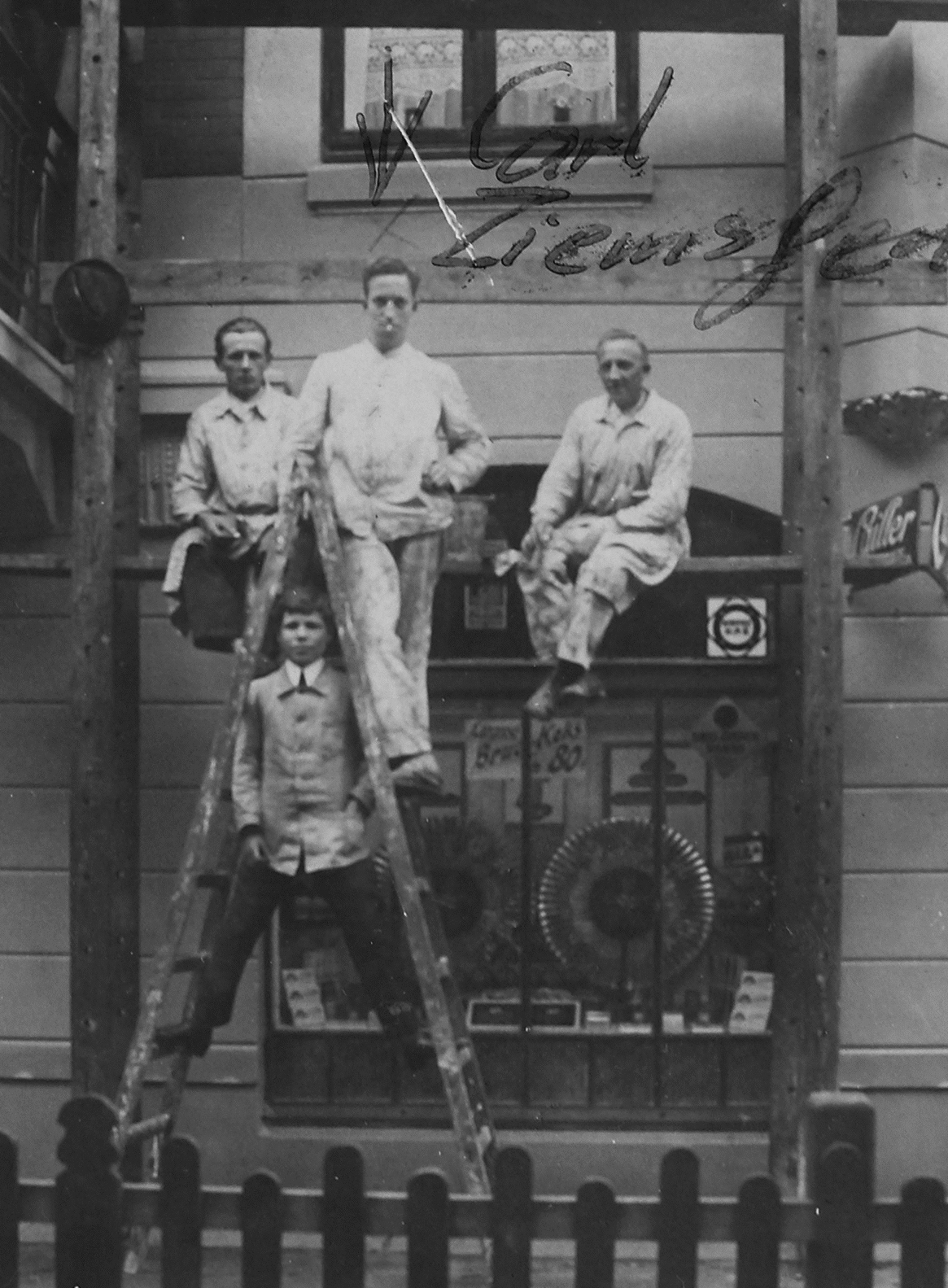

Over the past ten years, Edgar Ziemssen has compiled a chronicle of his family. That's how I learned more about his father and about himself. After the parents married in 1931, they lived and worked together with uncles and aunts in Hamburg-Hamm at Marienthalerstraße 10, house 2, first floor. Father was a sign painter and did his day's work in the living quarters, his sisters Martha and Clara mended tattered books, for Clara ran a lending library. Father's mother Marie was a page turner. Edgar remembers: "My parents' families were very different. They couldn't have been more different. His father came from a family where they were all atheists, pacifists, communists. My mother's family was Evangelical Lutheran. Very strict Baptists - strict with me, too. Soon both families had totally fallen out." Three years after the marriage the son was born, he remained the only child. He was named after Etkar André, the father's fellow fighter in the KPD, about whom the latter raved a lot. While the boy was growing up, his father was repeatedly imprisoned in concentration camps, usually for several months. Edgar did not learn what happened to his father.

The marriage of Carl and Käthe Ziemssen lasted only two years. Käthe Ziemssen, the mother, did not forgive the father for a misstep in married life and separated from him. "My mother was beautiful, hysterical and knew very well what she wanted. Whoever made a mistake once as a man, she sent into the desert," said son Edgar. "Even with jewelry, she could not be softened then. She only liked amber jewelry anyway." The father moved out and found a garret at Ipernweg 11 in Fuhlsbüttel.

"My father was a soul of a man. In the little time he had for me, he kept me busy a lot. In the tiny triangular garden with elder bush behind the house, he once dug until white sand appeared. That's how I came to have a sandbox. Although father didn't want to know anything else about war and weapons, the two of us once shot at targets with an air rifle in the hallway. Another time he started a gramophone, I stuck my head into the hopper and wondered why a whole orchestra should be playing in there. I turned to the music, whereupon Papa threw me up again and again until I hit something. I still have the scar today. Dad was probably on the road a lot for the party. After my parents separated, I grew up with my maternal grandmother. I was stubborn and took a lot of beatings, but there was nothing to be done with me by force. Mother kept me away from father. So I only saw him again briefly at my first day at school. At least he made sure that I wore a peaked cap when I started school, as befitted a Hamburg boy."

In the third year of the war, son Edgar came to Bavaria with the Kinderlandverschickung (evacuation during WWII of children living in bigger towns) and attended the village school in Hartkirchen. He remembers that year fondly. The farm family that took him in spoiled him. After his return, he spent another year in a children's home of the Diakonie (part of the protestant church) in Bad Oldesloe. Looking back, Edgar says: "Once, when I had done something wrong in Bad Oldesloe, I had to drop my pants as punishment, lie down on a chair, and then the head nurse hit me several times on my bare bottom with a wooden ruler. That hurt a lot, but was immediately forgotten." Due to the war, the Kinderlandverschickung did not come to an end for Edgar. Bad Oldesloe was followed by homes in the Baltic Sea resorts of Kellenhusen and Heiligenhafen.

The parents' marriage was divorced three years after the war began. In 1942, the father was killed in the Groß Rosen concentration camp. His mother, who lived until 1986, never spoke about the Nazi era. Edgar received his first school report when he finished the 3rd grade. Five decades after the war, Edgar began his research. He wants to know more. Especially Wolf-Peter Szepansky from the "Stiftung Hilfe für NS-Verfolgte" in Hamburg supported him initially in his research. Only now did Edgar learn about his father's political work and about the arrests and the closer circumstances of his death.

The father

Born in Hamburg in 1903, Carl Friedrich Ziemssen attended the public elementary school in Rothenburgsort and went on to an apprenticeship as a painter. During further training as a poster and lettering painter, he met Otto Richter, who was two years his senior. Richter had learned mechanical engineering, but was a painter. They became friends, and Otto married Carl's sister Martha. Edgar remembers well: "The two were always involved in discussions about world views. Later, when Uncle Otto was already somewhat better known as an artist in Hamburg, he took me to one of his exhibitions. Just like Vadder [father], he was in the KPD. When a comrade was wanted by the Gestapo during the Nazi era, Uncle hid him in his broom closet. The Gestapo also rang his doorbell, but could not find anything. Uncle Otto survived the war. Sometime after 1960 he died of lung cancer."

In May 1933, Carl Ziemssen was first imprisoned in the Fuhlsbüttel police prison (later known as "Kolafu") for three weeks. Again and again he was then sentenced and imprisoned. While at liberty, he earned a living as a painter's assistant. In 1936 he served time in the Glasmoor detention center and three months again in the "Kolafu"; in 1937 he was again sent to the "Kolafu" for three weeks, and in 1941 to the Harburg detention center.

After the war, the Hamburg District Court confirmed the family's conviction of his father for "offenses against § 2 of the law against insidious attacks on the state and the party and for the protection of party uniforms of December 20, 1934." What exactly had led to his imprisonment in Harburg Prison, Buxtehuderstraße 9, Carl Ziemssen hinted at in a letter to his mother on February 15, 1942: "Shouldn't you know why I'm here? Insulting the Wehrmacht (Heimtücke)." In the divorce proceedings in 1942, at which Carl could not be present in person because of his imprisonment in Harburg, his political views were also brought into the fray. The divorce decree states: "By committing this new crime, the defendant has again shown his bad character. In a war for the being of the German people, the defendant [...] insults the German Wehrmacht. By doing so, he not only puts himself in custody, but again exposes his family to hardship."

The Gestapo did not let him out of their clutches after he had served his ten-month prison term in Harburg. Upon his release, he was met at the prison gate by the Gestapo and taken to "Kolafu" for five weeks and then to Buchenwald. His mother Marie received from Buchenwald the only sign of life from her son, a letter: "Please send me a pair of father's shoes, my brown boots, a pair of stockings to change into and foot rags, which you can make from old flannel, I would be very grateful, and father's leather gaiters. [...] So send me the things, I need them very much." In mid-September 1942, sick with stomach, he was transferred from there to the Upper Silesian concentration camp Groß Rosen, where he died on October 4. The official cause of death was "acute cardiovascular failure”. Six weeks later, Carl's mother received his last belongings from the Hamburg Gestapo at Stadthausbrücke.

Postscript

Many years after I had the conversations with Edgar Ziemssen about his father, he died of cancer in May 2018.

Translation Beate Meyer

Stand: March 2023

© René Senenko

Quellen: StaH, 332-5 Standesämter, Geburtsregister 13939 u. 1786/1903 Carl Friedrich Ziemssen; StaH, 332-5 Standesämter, Heiratsregister 13592 u. 792/1931 Carl Ziemssen/Käthe Stolte; Aufzeichnungen von René Senenko über die Gespräche mit Edgar Ziemssen von November 2011 bis Januar 2012; von Edgar Ziemssen ausgearbeitete "Chronik der Familien Ziemssen/Stolte" sowie die dazugehörigen Dokumente und Fotos: Bescheinigung des Oberstaatsanwalts beim Landgericht Hamburg vom 27.8.1945, Az. 11 Ja. F. Sond. 176/41; Brief von Carl Ziemssen aus der Haftanstalt Harburg an seine Mutter, 15.2.1942; [Scheidungs-]Urteil des Landgerichts Hamburg, Zivilkammer 16b, verkündet am 3.3.1942, Az. 16b R309/41; Brief des Schutzhäftlings Nr. 975, Block 41, Carl Ziemssen, aus dem KZ Weimar-Buchenwald an seine Mutter, 12.5.1942, Sterbeurkunde, Standesamt Groß-Rosen II, Nr. 65/42, 4.10.1942, bestätigt durch das Standesamt Hamburg am 22.9.1953; Bescheinigung des Lagerarztes KL Groß-Rosen bzgl. Tod des Schutzhäftlings Ziemssen, Carl, 26.10.1942; Vorladung der Geheimen Staatspolizei, Staatspolizeileitstelle Hamburg für Maria Ziemssen, 19.11.1942; Liste der "Nachlass-Sachen des im Konz. Lager Groß-Rosen verst. Häftlings Karl Ziemssen" v. 3.11.1942; Vereinigte Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Naziverfolgten e. V. (Hamburg): Totenliste Hamburger Widerstandskämpfer und Verfolgter 1933–1945, Hamburg 1968, S. 97.

Anmerkung: Carl ist die Schreibweise des Vornamens laut Geburtsurkunde.