Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

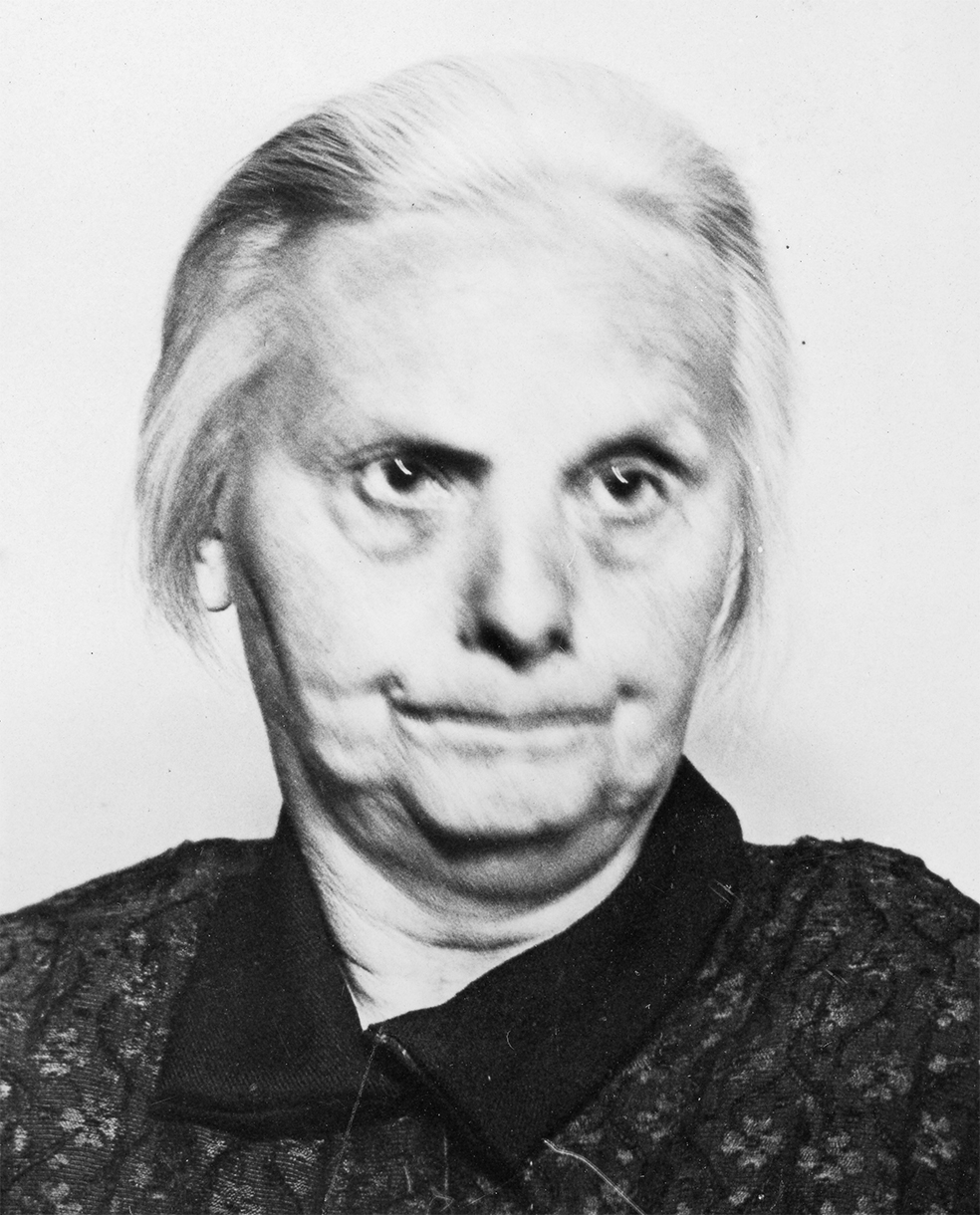

Ida Niederschuch * 1877

Carl-Petersen-Straße 27 (Hamburg-Mitte, Hamm)

HIER WOHNTE

IDA NIEDERSCHUCH

JG. 1877

EINGEWIESEN 1887

ALSTERDORFER ANSTALTEN

"VERLEGT" 1943

HEILANSTALT

AM STEINHOF / WIEN

TOT 14.10.1944

Ida Niederschuch, b. 1.17.1877 in Hamburg, Admission to the Alsterdorf Institute 2.6.1887, transferred on 8.16.1943 to the "Wagner von Jauregg Viennese Medical and Nursing Home," death there on 10.14.1944

Carl-Petersen-Strasse 27 (formerly: Hinter der Landwehr 27)

At age 10, Ida Niederschuch was personally admitted to the "Alsterdorf Institute" on 6 February 1887 by its founder, Heinrich Sengelmann, and lived there for 56 years until her removal to Vienna. In the mid-nineteenth century Heinrich Sengelmann had, with his own funds, created and built a facility for the pedagogic treatment of people with learning disabilities. Ida Niederschuch was first entrusted to him for an examination on 10 November 1884, remaining under his care until 17 December of that year. Her admission came about at the initiative of Senator Georg Ferdinand Kunardt. It was he who had commissioned a physician of the General Hamburg Institute for the Poor to examine the mental condition of Ida.

The girl suffered from epileptic seizures which caused her to fall and meant she was constantly reinjured. The doctor asserted firmly that her "mental powers were substantially retarded." While she could understand simple things from her mother, the physician could get no satisfactory answers to his questions. Although she was now seven years old, she broke her toys and tore up her clothing and other objects. The report ended with: "she is without any mental life" and "therefore thoroughly suited for the Alsterdorf Institute." After the five-week observation period, Ida Niederschuch returned home.

Ida’s parents were the miller Siegwart Niederschuch and his wife Dorette, née Therkorn, both "of Christian religion," according to Ida’s birth certificate; they lived then at Bankstrasse 98 in the Hammerbrook quarter of Hamburg. Siegwart Niederschuch, the son of a teacher, came from Punitz in the Prussian Province of Posen and was apparently the only member of his family to come to Hamburg. Dorette Niederschuch was from Harsefeld in the County of Stade (Lower Saxony). The couple had their daughter Ida baptized at the age of seven in the Church Congregation of St. Georg. Also belonging to the family was the five-year older brother Karl, who at first was an "auxiliary scribe" and later a chancery clerk in the County Court.

Siegwart Niederschuch died at 49 years on 8 June 1889, two years after Ida’s acceptance in "Alsterdorf." His widow hired out as a housekeeper or lived with her son, who married in 1895 and lived with his wife Emma, née Reichel, in Eppendorf. In 1896, their son Siegfried was born. The intensity of contact with Ida varied over the decades.

Beyond the standard paperwork concerning Ida’s admission to the Alsterdorf Institute, there is a handwritten memorandum from Heinrich Sengelmann about having received the amount of 96 Marks for clothing upon entrance.

Ida was considered "uneducable," showed symptoms of anaclitic depression, and scratched, bit, hit, spit, and tore her clothing. In the eyes of the staff, the only positive trait in Ida’s behavior was her attentiveness to her personal cleanliness. Noted positive reactions were that she would, upon request, pick up a fallen object and was able to undress by herself; she could not, however, dress or wash herself alone. Her sensory capacities were very narrowly limited: she heard her name and seemed to recognize her mother. If she were spoken to, she would softly repeat the last spoken words. The annual report of July 1892 concludes: "In order to direct her impulse to tear everything apart into more productive paths, "she is given linen and the like to tease, which she does quite beautifully."

A year later it was reported that she was physically healthier and that she did not tear her clothes so often.

The next year the talk was of general progress. Although Ida suffered from stiff joints and swollen feet, she was ambulatory. Her speech had not progressed beyond the echoing trait, but she liked to sing songs and showed a general pleasure in music. In contrast to her stereotypical rocking movements, she could express joy with the movements of her upper torso. She had lost her former shyness and had become more compatible with her fellow-patients, although she still liked to pull their hair. She experienced seizures much more rarely.

When Ida Niederschuch was 18 years old, in 1895, the report calling for her remaining at the institute was based on recurring epileptic seizures and physical and mental retardation.

A few months before the birth of her grandson Siegfried, Dorette Niederschuch moved from her son’s home and lived until the end of 1900 in the household of her widowed sister on Kieler Strasse. Apparently, she became psychologically ill, for she went from here to the "Friedrichsberg asylum" and a short time later was transferred to the "Langenhorn asylum," where she died on 26 January 1924.

Between 1910 and 1913, Ida Niederschuch had to be treated repeatedly in the infirmary because of scratches and boils. Shortly before the beginning of World War I, she was 37 years old by this time, setbacks in her physical and mental health were noticed. Every two or three weeks, almost always at night, she suffered severe epileptic seizures, waved her fingers uninterruptedly as though playing a violin, and showed a fondness for tearing shifts. How often she received visits or had contact with her brother cannot be ascertained in the records.

When Ida Niederschuch later contracted shingles, her weight was reduced to under 83 pounds; she hovered around 88 pounds in the following years. There is no information about her height; apparently, she was a small, delicate person.

In 1925, for the first time, Ida was put in a "straitjacket," to stop her from constantly taking off her shoes and stockings. A year later she was in the hospital because of a gastrointestinal infection; another time it was heart failure. A special event was noted in 1927, when her brother Carl sent a food package.

Ida’s condition was unchanged up until the next stay in the infirmary in May 1929 because of bronchitis. She suffered from eating disorders with bouts of continuous vomiting that alternated with a loss of appetite; then she began to eat regularly again reaching her maximum weight of 110 pounds in the summer of 1935. Shortly after this she lay in the infirmary with stomach bleeding and suspected stomach cancer. The heart problems returned once again.

On 26 April 1938, the Social Administrative Office of Hamburg extended coverage for Ida Niederschuch another ten years. She did not live to see the end of this period.

In general nothing changed in her condition. She remained helpless and in need of care. Her utterances were limited to: "I cannot, I will not," when it was time to eat, and when it was time for her afternoon bath, but not her morning bath: "Ida doesn’t like to bathe, Ida will not bathe, nooooooooooo." Otherwise, she spoke only when she wanted to go to bed. But Ida liked to hum along with songs.

From March 1943, she was almost constantly in a straitjacket because otherwise she would eat paper, yarn, etc. Perhaps it was this need for high maintenance that induced the institute’s directory, after the widespread destruction of Hamburg by the air bombardments of July and August 1943, which also damaged the Alsterdorf Institute, to transfer Ida.

On 16 August, she, along with 228 girls and women, was sent on a transport to the Wagner von Jauregg Viennese Medical and Nursing Home, arriving on the next day.

At her admission she weighed 81.5 pounds and her temperature was 97.5 F; her bearing was described as calm, but contrary and rejecting. The diagnosis was recorded as "congenitally feeble-minded" with dubious heredity.

Ida lost more weight, remained anxious lying in bed, played less with her fingers. She was moved to another ward, ate well again, gained weight, then fell more often and became ill with tuberculosis, from which she allegedly died on 14 October 1944, weighing less than 70 pounds. The autopsy established a lung inflammation, heart and kidney failure, with general weakness due to age. Ida Niederschuch was 67 years old and was buried in the Vienna Central Cemetery.

Carl Niederschuch had been bombed out and evacuated, losing all papers concerning his sister and all contact with her. In connection with a donation to the Alsterdorf Institute, he attempted in 1957 to replace and complete the documents with the help of the institute directors; he was referred to the Vienna institution’s directors. It took many more years before the archives were opened and Ida Niederschuch’s life history could be traced.

Translator: Richard Levy

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: November 2017

© Hildegard Thevs

Quellen: Staatsarchiv Hamburg, 332-5 Standesämter, 1892-263/1877; 265-456/1889; 2854-393/1895; 332-8 Meldewesen, K 6667, K 6742; Evangelische Stiftung Alsterdorf, Archiv, V 142; Wunder, Michael, Ingrid Genkel, Harald Jenner, Auf dieser schiefen Ebene gibt es kein Halten mehr. Die Alsterdorfer Anstalten im Nationalsozialismus, 2. Aufl. Hamburg 1988; Wikipedia "Evangelische Stiftung Alsterdorf", Zugriff am 1.10.2011; Stadtteilarchiv Hamm; Hamburger Adressbücher; Grundkarten Hamm.