Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

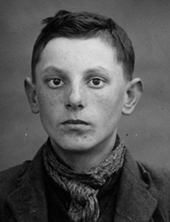

Walerjan Wróbel * 1925

Holstenglacis 3 (Untersuchungsgefängnis) (Hamburg-Mitte, Neustadt)

U-Haft

ermordet 25.8.1942

further stumbling stones in Holstenglacis 3 (Untersuchungsgefängnis):

Heinz Jäkisch, Bernhard Jung, Karl-Heinz Keil, Hermann Lange, Eduard Müller, Johann Odenthal, Johannes Prassek, Rudolf Schöning, Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, Walter Wicke

Walerjan Wróbel, b. 4.2.1925 in Fałkow, Poland, from 4.19.1941 a forced laborer in Bremen-Lesum, arrested on 5.2.1941, executed on 8.25.1942 in the Hamburg Remand Center.

Holstenglacis 3 (at the front of the Remand Center)

In the course of the Second World War, there were in Germany and the occupied zones over 20 million forced laborers, dragged from all over Europe to work in the armaments industries and also in private homes. Among the forced labors, the majority of which came from Poland and the Soviet Union, was 16-year old Walerjan Wróbel, who came to Bremen-Lesum from a peasant farm holding and who suffered from homesickness.

Walerjan Wróbel grew up in humble circumstances with two younger siblings and his parents in Fałkow, the County of Kon´skie, a little Polish village. At 14, he was let out of primary school and helped his father, a roofer, in the management of the family farm. His mother was named Marianne, née Uszczenska. On 5 September 1939, five days after the assault on Poland by the German Armed Forces, several houses in Fałkow were destroyed, including the house of Walerjan’s parents; thus, the living conditions in the village dramatically worsened. At first, after the occupation of Poland, "volunteers” were recruited for employment in the German Reich. In Germany, manpower was lacking because men had been called up to the armed forces. Because of the lukewarm response from "volunteers,” recruitment measures were stepped up. Village elders received the demand to provide a certain number of workers. Raids were conducted; people were arrested on the street. By the summer of 1940, a million Polish forced laborers were hauled off to Germany.

If one believes the notation made later in Walerjan’s prisoner’s personal documents, then he reported voluntarily for work in Germany. Perhaps, on 19 April 1941, when he arrived in a group "Reich labor” transport as an agricultural laborer at the farmstead of the widow Martens in Bremen-Lesum, he thought that it would go better for him than in his destroyed home village. However, unable to speak German and ill with homesickness, he attempted six days later to flee, was picked up by the police, and returned to the farm. Asked about the reasons for his flight, he answer that he got enough food, but that the work was too hard and that he longed for his family.

A few days later, on 29 April, when he was sent back from the fields to the farmhouse, in order to perform housework, he set fire to the straw barrier between the barn and the calves’ stall. Naively, he hoped that "as punishment” he would be sent back home. The farmer’s daughter discovered the fire, and although no great damage had been done, because Walerjan helped extinguish the blaze, she turned him in for arson. After his arrest by the Gestapo on 2 May 1941, he was taken to the Bremen detention center. On 28 June 1941, he was transferred to the Neuengamme concentration camp. There he had to do heavy labor in the so-called Elbe Squad, digging a 2-3 mile long canal from the brick works there to the Dove anabranch on the lower Elbe.

At Neuengamme, Walerjan Wróbel made friends with the two-year older prisoner, Michał Piotrowski, who had been arrested on a streetcar in Warsaw during the summer of 1940 and who, via Auschwitz, had been sent to Neuengamme.

In a 1985 interview, Michał talked about work on "Elbe Squad” and his experiences with Walerjan (see Ch. U. Schminck-Gustavus, "The Homesickness of Walerjan Wróbel”).

"With fully-loaded wheelbarrows, we had to steady ourselves over a footbridge and carry the earth from the side of the canal to the opposite bank. The canal is wide, perhaps twenty-five feet. Just two narrow planks span it and in the middle was a life jacket: You had to go over the bridge with your barrow. The bridge wobbled, and you weren’t wearing shoes, but rather these wooden clogs with which you could not keep your footing. Often it would happen that the barrow went wrong and fell down into the water. But without a barrow, you couldn’t get out: right away you had to jump from the bridge to save the barrow. I was together with Walerek (nickname for Walerjan) and always behind him with my barrow….Once it happened that Walerek was going along and his barrow fell into the water. The Kapo is standing there and watching. And Walerek can’t swim; a non-swimmer. And he has to jump. And he does jump. I see that he is going under and not coming up again. And I jump in behind him. I can swim. And the canal is deep at that spot, perhaps 6 or 7 feet. First, pull Walerek out to the canal bank. The bottom is so soft, slimy, that my feet were sinking in. And then, you know, throwing the first barrow out onto the bank, and then the second barrow, too. From this time on, you know, we were inseparable, always going one behind the other….Walerek was very young, very naïve. If you say to him: this or that is true, or, this or that is the way it is in the camp—he’d believe you immediately. He always talked about his parents, his sister, school.

There was conversation in the evening after roll call: Everyone told a little something. We were a trio: Walerek, Lutek, and me. When Walerek told about the fire, Lutek asked: How many buildings? the whole village? And Walerek would answer: no, just a barn. And even that did not burn down all the way. And then he would explain his theory, that if he did sloppy work, then they would throw him out and send him back home, and that’s why he set the fire....He told me a few times later on: if I don’t work as well as I did at home, and add to that the burning, then they will say: He is not a good worker. We don’t need his kind. Let’s throw Wróbel out! - and send him home! Or so he thought. He didn’t think that fire is called ‘sabotage.‘ It never entered his head. The whole time he was so naive. Totally naive. A child."

In consequence of the inhuman working and living conditions in the Neuengamme camp, Walerjan Wróbel fell seriously ill in a short time.

Michał Piotrowski reported that a prisoner doctor from Warsaw by the name of Mittelstädt helped him and confirmed a general weakening due to malnourishment, blue bruises from beatings all over his body, and above all great nervousness. In 1941, an epidemic of spotted typhus broke out and the camp was put under quarantine; the friends lost sight of each other. Walerjan was put in another work squad, in which the young were given less strenuous work to do than in the "Elbe Squad.” "This squad existed for a few weeks. But I no longer saw Walerek because he was then in a different barracks block.”

Michał Piotrowski assumed that Walerjan Wróbel, because of the approaching legal proceedings, was isolated in a bunker away from the other prisoners. "During the quarantine, it was very difficult to get any sort of news. But, later, when the quarantine was lifted, I sought out Walerek. I asked many prisoners whether he had perhaps been hung or shot in the camp. But nothing. No one knew anything. From Stefan Kumer - he was another Polish prisoner, no. 4767 - I finally heard that after the quarantine, Walerek was put on a transport. An individual transport, the way out of Neuengamme. That was the last I heard about Walerek. After that - I heard nothing more.”

Walerjan Wróbel was, on 8 April 1942, almost a year after the fire in the barn, transferred back to the Bremen detention center, for prisoner interrogation. Despite his minority, on 8 July 1942, he was sentenced to death by special court proceedings as an "enemy of the people” for the act of arson. The "Juvenile Court” procedures did not apply to him because he was a Pole. One day after the judgment, Walerjan wrote a farewell letter to his family which was smuggled out of the jail.

In the name of the Reich Minister of Justice, a mercy plea by defense attorney Bechtel, dated 20 July 1942, was rejected by Roland Freisler (b. 1893 in Celle, d. 1945 in Berlin), the later president of the People’s Court.

On 24 August 1942, there followed a transfer from the Bremen-Oslebshausen penitentiary to Hamburg. On 25 August 1942 in the Hamburg remand prison on Holstenglacis Strasse, at 6:15 in the morning, Walerjan Wróbel, aged 17, was beheaded by Executioner Hehr of Hanover (b. 1879, d. 1952). His corpse was sent to the Anatomical Institute of the University of Hamburg for purposes of research.

In 1980, Christoph U. Schminck-Gustavus published the history of Walerjan Wróbel in the book, The Homesickness of Walerjan Wróbel.

In 1987, Walerjan’s trial was reopened and the National Socialist judgment was repealed. To remember the many Bremen forced laborers, a Walerjan Wróbel Association was founded around this time.

On 25 August 2007, in Bremen, the dike road on the left bank of Lesum River was officially renamed "Walerjan-Wróbel-Weg." In attendance at the unveiling of the memorial tablet on the Lesum tidal barrier, were his sister and three companions from Fałkow.

Translator: Richard Levy

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: June 2020

© Susanne Rosendahl

Quellen: StaH 242-1 II Gefängnisverwaltung, Abl. 12, 714 Wróbel; StaH 332-5 Standesämter 1152 u 432/1942; Schminck-Gustavus: Heimweh, S. 40–65; Diercks: Verschleppt, S. 18; https://www.stiftung- denkmal.de/jugendwebsite/r_pdf/walerjan.pdf (Zugriff 3.5.2013).