Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

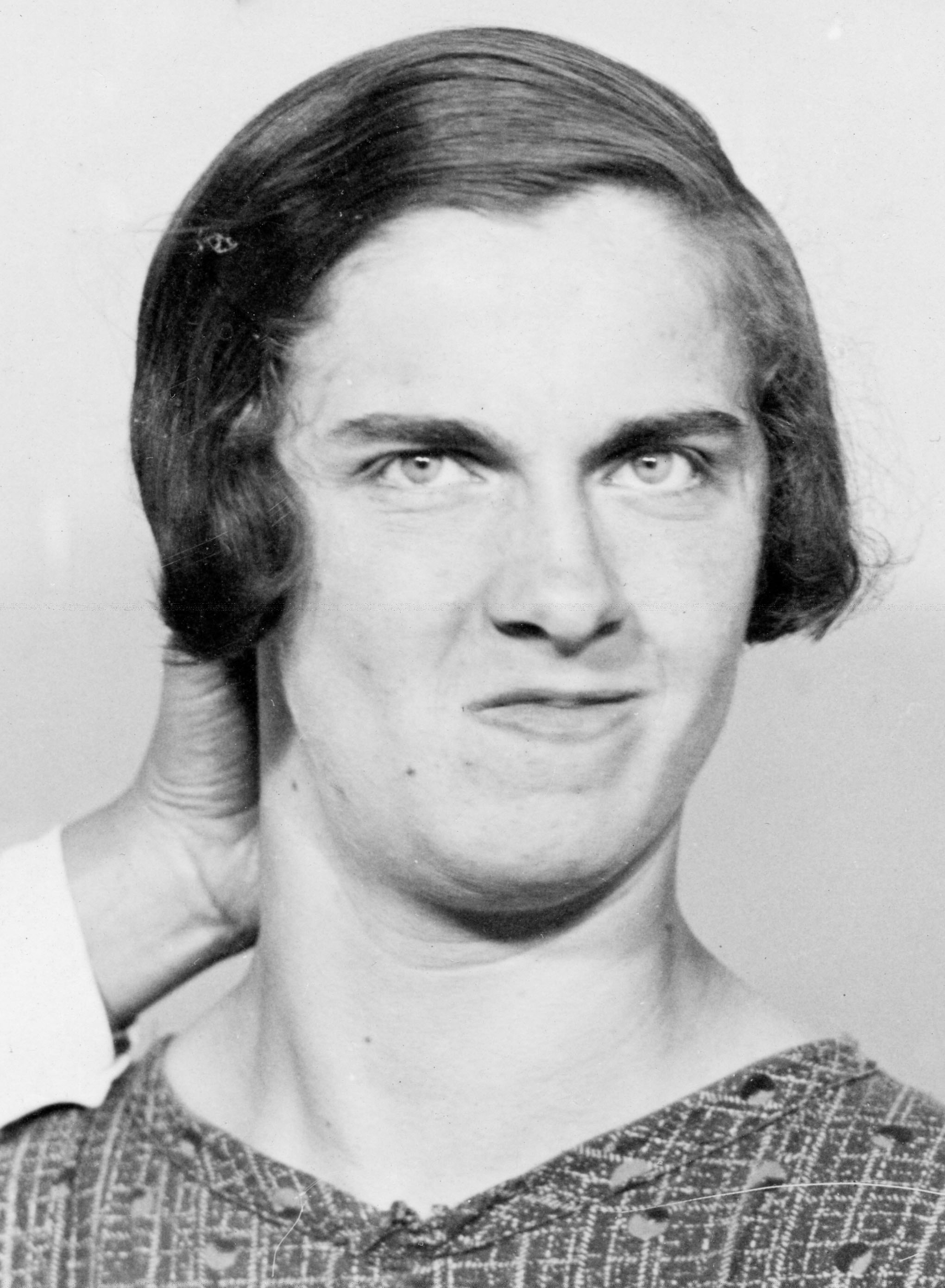

Gabriela Kock * 1916

Rübenkamp 6 (Hamburg-Nord, Barmbek-Nord)

HIER WOHNTE

GABRIELA KOCK

JG. 1916

EINGEWIESEN 1920

ALSTERDORFER ANSTALTEN

"VERLEGT" 16.8.1943

HEILANSTALT

AM STEINHOF WIEN

ERMORDET 24.11.1944

Gabriela "Ella" Kock, born 22.10.1916 in Dornbusch (district Drochtersen), admitted to the former Alsterdorfer Anstalten (now Evangelische Stiftung Alsterdorf) on 15.6.1920, transferred to the "Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt der Stadt Wien" in Vienna on 16.8.1943, died there on 24.11.1944

Rübenkamp 6/corner of Hufnerstraße (Barmbek-North)

Gabriela Magdalena Metta Kock, called Ella, was the daughter of the shipmaster (for special boats in the Hamburg harbor like so-called Ewer and Schuten ) Gustav Friedrich Kock and his wife Anna Adele Hedwig Kock, née Junge. Gabriela was born on Oct. 22, 1916 in Dornbusch, a district of Drochtersen (part of district Kehdingen). At the time of her birth, her father had been drafted into the war as a sailor and had been deployed on the battleship "Prinzregent Luitpold", which had taken part in the Battle of Skagerrak (31.5.-1.6.) in 1916, but had remained undamaged. The mother had gone to Drochtersen, about 70 km upstream from the mouth of the river Elbe, presumably to her sister-in-law Bertha Maria Junge.

However, the Kock family lived in Hamburg, Rübenkamp 6, II. floor, near the Barmbek train station. In the five-story house with 18 rented apartments lived mainly workers, but also a merchant and a police officer. On the first floor there was, among other things, a drugstore. Five days after her birth, Gabriela was baptized in the Lutheran congregation of Drochtersen. Gabriela Kock had an older brother, Heinrich Gustav, who died in 1914 ten days after his birth after a spinal cord operation in Hamburg's Marien Hospital, and a younger brother, Helmuth, born on September 22, 1919.

In the spring of 1917, at the age of four to five months, Gabriela's "present condition” was noticed, according to a memo in 1920. The General Institute for the Poor in Hamburg (from 1920 Welfare Office, from 1928 Social Welfare Authority) became responsible for the Kock family in 1920. On June 10, 1920, this authority wrote to the then Alsterdorfer Anstalten (today's Evangelische Stiftung Alsterdorf) in Hamburg: "It has been decided to transfer Gabriela, child of Gustav Kock, born in Dornbusch on X. 22, 1916, to the Alsterdorfer Anstalten. We inform you of this with the humble request to take in the aforementioned person and to notify us of the admission."

Two days earlier, the institution had filled out an "Ueberweisung in eine Hamburgische Anstalt für Geisteskranke, Idioten und Epileptiker" (transfer to a Hamburg institution for the mentally ill, idiots and epileptics) and had indicated Gabriela's "main manifestations of the illness" as follows: "without speech" and "great restlessness". The form was signed by the father Gustav Kock. On June 15, 1920, the three-and-a-half-year-old was admitted to the Alsterdorf institutions.

On the "Abhörungsbogen" (questioning and admission form) it was noted that she could neither walk nor talk and could not eat alone. The prescribed examination was carried out by the physicist Schulze of the Hamburg police authority (Department I, General Police) on July 1, 1920, and he confirmed the illness as "idiocy" (an outdated term for a severe form of intelligence impairment) and the decision that she was to be transferred to the Alsterdorf institutions. The expert witness was probably the court physician F. L. O. Schulze, a physician for nervous and mental disorders, whose office was located in the harbor hospital.

At the institution, Gabriela Kock received regular visits from her family. From May 1921, she was taken home for a day on average once or twice a month, and for four days at Christmas 1922. From 1924, the intervals changed, and she was now usually sent home on leave every two months for three to seven days, with permission granted by the management of the Alsterdorfer Anstalten. For the first time in August 1932, a mother's application for leave was rejected for "educational reasons," as the file stated.

In April 1925, Gabriela was admitted on a trial basis to the preschool of the institution's school, but was taken out again as early as August 1925 due to a lack of space. However, from May 1928 she was able to be there permanently. In the spring of 1929 and spring of 1930, the class teacher prepared school reports on her. Classes were held four afternoons for 1 ½ hours each. "She immediately attached herself to her teacher in great love and attachment, and this love was probably the spur to Ella's brisk zeal and diligence in the lessons. Her language improved a lot and Ella would make quite good progress in special language lessons [...]. In drawing, painting and modeling she makes great efforts, but she is very much handicapped by her twitches. [...] She received regular visits from her relatives, mostly on Wednesdays and Sundays, who brought her gifts each time."

In an interim report to the welfare authority (before 1939 renamed social administration, to which the welfare office was also subordinate) of March 18, 1938, the deputy director of the Alsterdorfer Anstalten, NSDAP and SA member Gerhard Kreyenberg (1899-1996), described the current condition of the 21-year-old as follows: "The patient suffers from epilepsy with athetosis and imbecility of medium degree. In personal hygiene she is independent and orderly, is occupied with light housework. She is generally calm, but in the last few months she has often been irritable and obstinate. Further institutionalization is required." According to the file, the epileptic seizures were treated with the sedative Luminal in 1940/1941: more severe seizures and multiple seizures with 0.2 mg, for lesser severity with 0.05 mg.

For more than 20 years, from 1922 to 1943, Gabriela Kock was housed in Ward 56. On June 17, 1943, she was transferred to Ward 4 "for educational reasons." The file noted: "Patient is extremely difficult in nature. She has been in Ward 56 for 9 years, but now had to be transferred for educational reasons. She is physically handicapped, but mentally very active. She has a strong will of her own, which she almost always uses to torment her fellow human beings, although at other times she can be very kind and understanding when she wants to be. She had already been temporarily transferred several times, it was always tried again with her. Now she doesn't fit into the departmental order at all, switches on a whim, constantly resists."

The last entry of the Alsterdorf institutions on August 16, 1943, was: "Due to severe damage to the institutions by bombing, transferred to Vienna. Dr. Kreyenberg." At this time, the almost 27-year-old patient weighed 50 kilograms, which was already well below her average weight of 54 to 56 kg for the years 1934 to 1940.

Together with another 227 women and girls with mental disabilities, Gabriela Kock was transported from the Alsterdorf institutions by special train to Vienna to the "Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt der Stadt Wien" (Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- and Nursing Institution of the City of Vienna), located on the grounds of Am Steinhof - officially to free up beds for bombed-out and war victims in Alsterdorf. The transfer to Vienna was carried out by the patient’s transports "Gekrat”, the Gemeinnützige Kranken-Transport-GmbH from Berlin W 9 (Potsdamer Platz 1), a sub-organization of the central office at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin, from which the systematic murder of 70,000 people with disabilities in six killing centers had been organized in a first phase of the sick murders.

The institution Am Steinhof was already heavily overcrowded before the arrival of the transport from Hamburg, and there was also a shortage of doctors and nurses who had been drafted for war service, which resulted in neglect of the patients. There was also a shortage of medicines, food and heating material in the war economy, and mortality increased accordingly. Gabriela Kock was officially assigned "rations class III," as noted in her file. However, the ration rate of the Am Steinhof institution had been massively reduced, so that the state subsidy for patients in ration class III was only 2.80 Reichsmark (RM) per day, compared to 7.33 RM at the Vienna General Hospital and 4 RM at the Alsterdorfer Anstalten in Hamburg.

During the National Socialist era, the Am Steinhof institution was assigned tasks within the framework of the euthanasia measures. The euthanasia murders in Vienna continued even after the alleged end of the murders of the sick in August 1941; false statements concealed the killing by medication, mostly an overdose of the sleeping pill Veronal or the sedative Luminal, as well as inadequate nutrition and nursing neglect.

In December 1943, Gabriela Kock weighed only 43.5 kg, and in July 1944, only 37 kg; thus, she had lost thirteen kilograms of weight in eleven months since her admission to the Vienna asylum. On January 10, 1944, the institution staff conducted a so-called Rorschach test with her. This controversial experiment, also called the "inkblot test," was used to examine a person's personality and any disturbances in their psychological state. The patient's file noted at the beginning of the entry "Duration: 10 minutes" as well as a crossed-out zero behind the numbers for the picture panels 1 to 10 and below that "Number of answers 0."

This "inkblot" test had also been administered to Käthe Vollmers and Käti Schultze (see for both www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de) in the same month.

For February 7, 1944, it was noted in the file: "Transfered to the nursing home”. Gabriela Kock was last accommodated in November 1944 in Pavilion 24, for which physician Nadeschka Gilnreiner was responsible, as well as for Pavilions 19 and 21.

On November 24, 1944, Gabriela Kock died at the age of 28. Her file shows no entries in the six months before her death. Information on the pavilion numbers in which she was housed in the meantime is also missing. Only Gabriela's death was entered in the patient's file by the doctor responsible for the pavilion on November 24, 1944, adding her abbreviation "Giln." to the note, countersigned with the abbreviation "Dy," presumably by Dombrowsky.

Gabriela Kock's body was autopsied. The diagnosis according to the autopsy protocol was: "Marasmus spychosi, epilepsy, brain damage". The pathological-anatomical diagnosis was: "Bronchitis muco-purulenta diffusa, Bronchopneumonia loborum inferiorum" (= type of pneumonia), "Myodegeneration cordis" (= heart disease).

The chief physician and pathologist Barbara Uiberrak (1902-1979) performed the dissection on the day of death. Her very brief dissection protocol avoided, as in many of her other dissections, a description of the external condition of the corpse as well as information on body size and weight.

The focus of the dissection was on the brain, which was removed and weighed. In gradations regarding the amount of text in the protocol, the lungs and heart followed. Liver and kidneys were mentioned only very briefly. Whether organs were permanently removed was not noted. The protocol was countersigned at the bottom right with two abbreviations: in the first place presumably by Karl Wunderer and with "Dy" (presumably Dombrowsky) in the second place.

Since 1943, the brains of about half of all dissected corpses were removed for histological examinations and a part was kept in a brain anatomical collection. Until 2002, the Vienna Institution still possessed 700 brains that had been removed during dissections. They were not buried until 2002 at the Vienna Central Cemetery (grave location group 40).

Gabriela Kock's father was informed of his daughter's death by telegram, as prescribed by the guidelines of the head of the clearing office of the sanatoriums and nursing homes of July 10, 1943. How little he knew about his daughter's condition since Gabriela's "transfer" to Vienna is made clear by his typewritten letter of November 28, 1944 to the "head of the sanatorium of the Heilanstalt Wagner Sauregg" (sic) and the questions for details contained therein: "Dear Director! I take the liberty of asking you for the kindness of sending me a few lines about the last days of the life of my daughter Gabriele, who, according to your telegraphic notification, died on November 24. My wife and I are so saddened by this news that my wife in particular would be comforted and reassured if she received a few lines from you that would clarify the state of her illness and the circumstances of her passing. I take the liberty of asking the following questions with the request for an answer: Did our daughter suffer particularly before her death? Was anyone with her when she died? When was she buried and where is she buried? In advance I thank you for your efforts, also in the name of my wife, and remain - your devoted Gustav Kock."

Karl Wunderer, who had made Gabriela's first examination after her arrival in Vienna and was responsible, among other things, for Pavilions 2 and 10, answered him euphemistically on December 6, 1944, "that your daughter Gabriele died on the 24th [November] at 4 a.m. of pneumonia, which she had probably contracted by swallowing during an epileptic seizure. As she was also suffering from degeneration of the heart muscle, she was so dazed during the last days of her life that she probably hardly realized the seriousness of her condition. The chief nurse of the department was present at the patient's demise. The body was buried at the Vienna Central Cemetery and you can inquire about the grave site at the cemetery administration."

We do not know if Gabriela's parents learned their daughter's grave location. An inquiry at the Vienna Central Cemetery in 2020 revealed that Gabriela Kock's name is not listed there. During the "war period," it was said, the names of all the dead had not been recorded.

Of the 228 female patients transferred from the Alsterdorf institutions to Vienna, 196 had died by the end of 1945, or 86 percent. It can be assumed that this was due to deliberate malnutrition, failure to treat illnesses, or deliberate overdosing of medication on the part of the asylum staff.

Translation by Beate Meyer

Stand: February 2022

© Björn Eggert

Quellen: Adressbuch Hamburg (G. Kock), 1941, 1943 (tätig als Schiffer, wohnhaft Rübenkamp 6); Telefonbuch Hamburg 1939 (Reichsstatthalter C 12 Sozialverwaltung, früher Fürsorgebehörde Hamburg); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter) 707 Sterberegister 1914 Nr. 379/1914 (Heinrich Gustav Kock); Archiv Evangelische Stiftung Alsterdorf, Sonderakte 180 (Gabriela Kock); Harald Jenner/Michael Wunder, Hamburger Gedenkbuch Euthanasie. Die Toten 1939-1945, Hamburg 2017, S. 305 (Gabriela Kock, Sterbedatum 4.10.1944); Peter von Rönn u.a., Wege in den Tod. Hamburgs Anstalt Langenhorn und die Euthanasie in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, Hamburg 1993, S. 443, 446-447, 457-459, 465 (Der Steinhof in Wien, darin Erwähnung von Dr. Wunderer, Dr. Nadeschka Gilnreiner und Dr. Dombrowsky); Susanne Mende, Die Wiener Heil- und Pflegeanstalt "Am Steinhof" im Nationalsozialismus, Frankfurt/Main 2000; Peter Schwarz, Mord durch Hunger. "Wilde Euthanasie" und "Aktion Brandt" am Steinhof in der NS-Zeit, Vortrag im Rahmen des Symposiums "Zur Geschichte der NS-Euthanasie in Wien", Wien 2000 (Einsparungen, Verpflegungskostensatz Am Steinhof); Michael Wunder/Ingrid Genkel/Harald Jenner, Auf dieser schiefen Ebene gibt es kein Halten mehr. Die Alsterdorfer Anstalten im Nationalsozialismus, Stuttgart 2016, S. 331-371 (Transport nach Wien); Götz Aly, Die Belasteten, Euthanasie 1939-1945. Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Frankfurt/ Main 2013, S. 126 (Barbara Uiberrak); Herbert Diercks, "Euthanasie". Die Morde an Menschen mit Behinderungen und psychischen Erkrankungen in Hamburg im Nationalsozialismus, Hamburg 2014, S. 33 (Alsterdorfer Anstalten); Institut für Soziale Arbeit Hamburg, zusammengestellt von Dr. Clara Friedheim, Führer durch die Wohlfahrtseinrichtungen Hamburgs, Hamburg 1926, S. 99 (Alsterdorfer Anstalten); Wiener Zentralfriedhof, Infopoint. http://gedenkstaettesteinhof.at (Gedenkstätte Steinhof, Ausstellung: Der Krieg gegen die "Minderwertigen". Zur Geschichte der NS-Medizinverbrechen in Wien, eingesehen 31.10.2020); www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de (Margarethe Käti Schultze, Käthe Vollmers).