Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

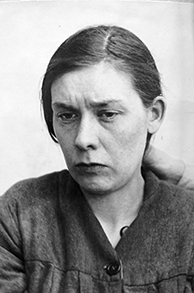

Erna Dreyer * 1897

Pappelallee 51 (Wandsbek, Eilbek)

HIER WOHNTE

ERNA DREYER

JG. 1897

EINGEWIESEN 1943

"HEILANSTALT"

AM STEINHOF WIEN

TOT AN DEN FOLGEN

14.7.1945

Erna Dreyer, née Thielck, born on 20 Nov. 1897 in Hamburg, died on 14 July 1945 in the Vienna Municipal Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt

Pappelallee 51 (Pappelallee 53)

Erna Dreyer died at the age of 47 of emaciation, combined with a psychological disorder, two months after the end of the Second World War in the Heil- und Pflegeanstalt "Am Steinhof,” a sanatorium and nursing home in Vienna. Just how, as a resident of Eilbek, she got there and became a victim of euthanasia even after the war had ended, can be reconstructed only in rough outline.

Erna Dreyer came from a German-Swedish family. Her mother was born as Johanne Kirstine Petersdotter in southern Sweden on 31 May 1860; her father, Friedrich Johann Jochim Thielck, was born on 12 Apr. 1865 in Jürgenshagen near Bützow (Mecklenburg) and had trained as a tailor.

What emerges from the children’s entries in the register of births is that the married couple came to Hamburg by the 1890s at the latest and lived at Lange Reihe 89 in St. Georg. On 7 May 1895, Johanne Thielck gave birth there to the twins Anna Dorothea, who died of pneumonia at a young age, and Alma Alwine. The third daughter, Erna Johanna Louise, was born on 20 Nov. 1897 at Lühmannsweg in Eilbek, the quarter of the city in which she grew up and started her own family.

Erna attended the eight-grade elementary school (Volksschule) on Kantstrasse. She had a hard time with learning, and especially math was difficult for her. Therefore, she repeated two grades, and after grade 3, i.e. grade 6 according to today’s way of counting, she left school. At 14, without a school diploma, the only path open to her in order to contribute to family income was to take a position as a domestic servant with a family. She found various posts as a maid.

After the end of the First World War, Erna met the mover Hermann Wilhelm Karl Dreyer, born on 24 Dec. 1886, who was eleven years her senior. When Erna was eight months pregnant, they got married on 19 Feb. 1921 and lived together in the home of Friedrich and Johanne Thielck, who also supported their older daughter Alma Alwine and her (illegitimate) child.

Erna Dreyer’s first child lived only for a few weeks. On 22 Feb. 1922, her father, Friedrich Thielck, also died in the shared apartment on Pappelallee. About one year later, on 23 July 1923, Erna gave birth to a second child, a healthy boy.

Erna attracted her family’s attention because she moved very slowly, steered clear of housework, and evaded contacts with her neighborhood. Due to this behavior, she was admitted for observation to what was then the Friedrichsberg State Hospital in Apr. 1924. During the admission procedure, Mr. and Mrs. Erna and Hermann Dreyer criticized each other in the presence of the admitting physician: the husband found his wife "stupid,” she in turn had a hard time with his alcohol consumption, adding, however, in an extenuating manner, "He is with the furniture and anyone who is with the furniture drinks. So does he.” Erna’s examination provided no indication of any physical disorders. After three weeks, Hermann Dreyer took his wife home from the hospital at his own request, signing a written declaration to that effect. Since he did not expect any improvement of her state, he preferred to have her with their child and with him. Upon her discharge, the physician confirmed a slight improvement of her condition.

The slight improvement did not last for long. Erna neglected her husband and her son, ran away from home, went into fits of rage from time to time, and behaved "childishly.” She became pregnant again and, for reasons not described in any detail, was admitted for treatment to Barmbek General Hospital. From there, she was transferred once again to "Friedrichsberg” on 1 Apr. 1926 and admitted with a diagnosis of "chronic psychosis, uncertain schizophrenia.” This vague classification of medical conditions did not change fundamentally over the course of her treatments.

At the time of admission, her size was recorded at 1.66 m (approx. 5 ft. 5 in.) and her weight at 62 kilograms (136.5 lbs.), and the examination determined that she was suffering from latent syphilis. Erna insisted on never having been sick and being healthy even then. The only physical medical findings concerned the reflexes of her pupils and of her patellar tendons. In the interview with the physician, she repeatedly came back to the issue of food. Supposedly, she lived on a diet of milk and apples. In accordance with the latest standard of syphilis therapy at the time, she underwent malaria treatment for the purpose of curing her and protecting the unborn child from infection. Mother and child came through the treatment well, and in July, Erna Dreyer temporarily returned to Barmbek Hospital for delivery. The newborn child was transferred along with his mother to "Friedrichsberg” for further treatment. Just how long the infant stayed with Erna and who took care of him afterward is not known.

Erna began working in the sewing room. Whenever addressed, she routinely answered that she wished to be released. One day she cut her braid in the middle and flushed it down the toilet. Staff surmised that she hoped to force her discharge in this way but instead she was brought to the "observation room” (Wachsaal – a room in which patients were immobilized and underwent continuous therapy; see entry on Harry Becker), where she was under constant surveillance.

Upon returning to her ward, she was unchanged in terms of behavior. She knitted, went for walks in the garden and on leave to see her mother, or received visitors who also provided her with food supplies. All of these encounters were forgotten immediately, whereas she was constantly preoccupied with the thought of food, complaining that she never received a parcel. She sent her husband a postcard inviting herself to his place to celebrate her mother’s birthday, something she associated with the hope of seeing her small son again. By then, Hermann Dreyer had rented an apartment on Kantstrasse.

Erna Dreyer’s condition worsened. She became even more off-putting, and her lack of independence increased. Whereas at "Friedrichsberg” she was located at relatively close quarters to her family, she was completely separated from them in geographic terms by the transfer to what was then the Langenhorn State Hospital on 12 Jan. 1929. By that time, she was 32 years old. Her settling in was disrupted by several transfers within the institution. Despite her joy in eating, Erna did not eat independently, standing up with her torso bent over slightly, turning away her face, and avoiding any contact with her environment. Most of the time, she spoke at an unintelligibly low voice to herself or grumbled. She refused both activities offered and demanded.

In 1932, Hermann Dreyer, her husband and at the same time the caregiver appointed for his legally incapacitated wife, took a first step toward divorce. He asked the institutional administration for a prognosis concerning the further development of the illness, which turned out ambiguously. The authorities appointed a guardian to represent Erna Dreyer in the divorce proceedings, which ended in a divorce on 20 Mar. 1933.

After another two years in "Langenhorn,” Erna was transferred again in 1935. After the closure of the Friedrichsberg State Hospital, the "Langenhorn” institution had to admit 641 patients, causing it in turn to look for more space. The institutional administration was able to accommodate chronically ill patients in the Emilienstift, a nursing home of the Anscharhöhe foundation in Hamburg-Eppendorf, a Christian institution, and Erna Dreyer, too, was transferred there. Her interest continued to focus on eating and drinking; she managed dressing and undressing on her own. Year after year, nurse Gertrud noted that Erna was "unchanged, apathetic, and indifferent,” if applicable adding small alterations, e.g. in 1940: "she mostly has her hands on her head, feeling around on her face.”

The heavy Allied air raids at the end of July/early Aug. 1943 also destroyed the homes of Erna’s relatives on Pappelallee, which severed contact to them. By then, Hermann Dreyer lived at Pappelallee 1 with his new wife. Immediately after the end of the bombings, on 7 Aug. 1943, Erna was re-transferred from the Emilienstift, where she had lived for eight years, back to "Langenhorn” and then to Vienna only a week later.

In the course of the German Reich’s planning concerning disaster medicine, the psychiatric institutions had to set up auxiliary military hospitals or were converted into such facilities. For regions threatened by air raids or even destroyed, such as Hamburg, an added element was that patients were brought to safe areas. As a state institution, Langenhorn was integrated into these measures on a large scale. Supported by the Hamburg health care administration and various authorities in Berlin, the institutional management organized transports to sanatoria and nursing homes located farther away. Even after the stop of institutional "euthanasia,” the T4 head office in Berlin played a crucial role. On 16 Aug. 1943, the "charitable ambulance organization”(Gemeinnützige Krankentransport GmbH – "GekraT”) transported several hundred patients of what was then the Alsterdorf Asylum (Alsterdorfer Anstalten) and the Langenhorn State Hospital on the feared gray busses to Langenhorn freight station. There, women and girls had to transfer to a train, those unable to walk were reloaded. On 17 Aug., they arrived at the Vienna Municipal Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt, a sanatorium and nursing home, the former "Am Steinhof” model institution, and went through the usual admission procedure. Erna Dreyer was "disoriented, patiently enduring the physical exam, and answering quietly, with few words, including some neologisms.” She knew the correct answers to the multiplication problems of 3 times 3 and 3 times 17 but not to others. After a few weeks, she had settled in and spent her days in the common room, except when she had to stay in bed because of her severely swollen legs. For the first time, the institutional reports viewed her apathy and hesitant responses in the context of inhibition, and they indicated specifically that Erna never expressed any wishes.

Her weight fluctuated slightly around 50 kilograms (110 lbs). One year after her admission, she was transferred to the local nursing home. By that time, she hardly ever left her bed, no longer spoke, though nodding her head to communicate, and continued to lose weight. Her weight dropped to 34.5 kilograms (76 lbs) in July 1945.

After the end of the war, she was thoroughly examined and questioned one more time on 30 June 1945. The physician managed by direct address to establish contact with her. Erna was unable to answer his question why she had come to Vienna. However, she spoke of a parcel she had received after delivering her daughter, by then 19 years old, who had come to her at the institution. Indeed, she had given birth to her third child at Barmbek Hospital 19 years before, on 6 Aug. 1926.

On 14 July 1945, Erna Dreyer died of "emaciation in conjunction with a psychotic condition.” The institution sent one postcard each to the mother and the divorced husband to Pappelallee in Eilbek. Both cards were returned to sender as undeliverable due to the destruction of the house. Moreover, Erna Dreyer’s mother, Johanne Thielck, had died at the home of her son-in-law in Fuhlsbüttel on 8 June 1944. Both cards were concerned with Erna Dreyer’s funeral. Since no reply was forthcoming, her corpse was handed over to the City of Vienna for burial.

Status as of Feb. 2014

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

© Hildegard Thevs

Quellen: AB; Krankenakte der Wagner von Jauregg-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt, Wien, fotografiert von Ingo Wille im Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv, Wien, 2012; StaH 213-12 Staatsanwaltschaft Landgericht NSG, 0013/001 Quickert-Verfahren; 332-5 Standesämter 2364-1202 u. 1203/1895, 2440-2259/1897, 6593-69/1921, 7026-136/1922, 7279-536/1944; Jenner, Harald, 100 Jahre Anscharhöhe 1886–1986; Rönn, Peter von, Die Entwicklung der Anstalt Langenhorn in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, in: Böhme, Klaus, Uwe Lohalm, Hg., Wege in den Tod, S. 27-136; Wunder, Exodus von 1943 in: Wunder/ Genkel/Jenner, Auf dieser schiefen Ebene; Michael Wunder, Die Auflösung von Friedrichsberg, 1990.