Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Stolpertonstein

Biografie: Astrid Louven

Albert Freytag * 1916

Schädlerstraße 1 (Wandsbek, Wandsbek)

1944 Heilanstalt Obrawalde

ermordet am 1.2.1944

Albert Freytag, born 28 Apr. 1916, murdered 1944 in the Meseritz-Obrawalde Institution

Schädlerstraße 1 (Neue Bahnhofstraße 1/Horst-Wesse-Straße 1)

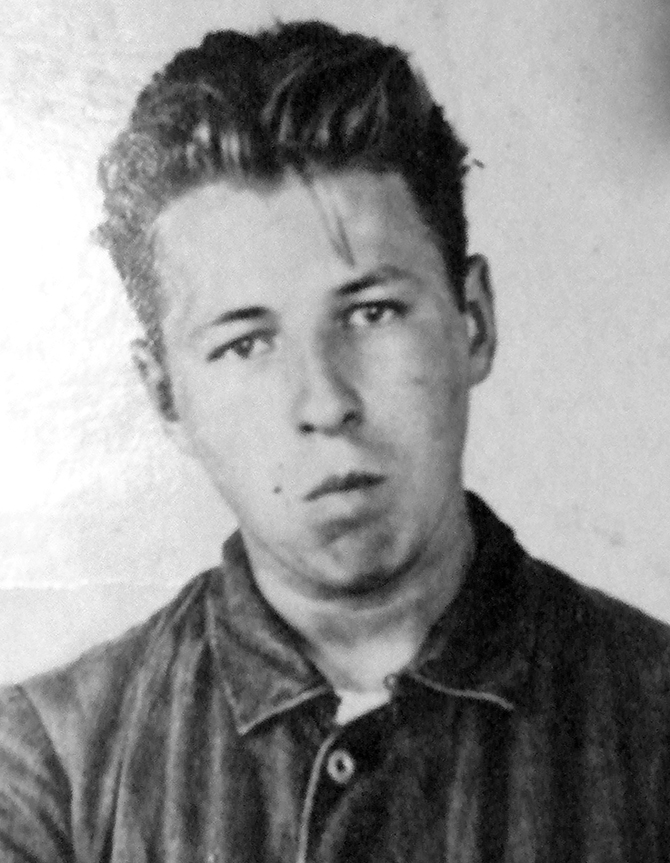

A photograph in the hospital records shows a handsome young man looking challengingly into the camera. His expression gives no indication that his life had been star-crossed from the start.

Albert Freytag was born out of wedlock in the times of scarcity during the First World War on 28 Aril 1916 in Wandsbek. His Protestant mother, Olga Freytag, worked as an office clerk, and his Jewish father, Sally Herzberg, as a butcher and road haulier in Wandsbek (see chapter: Herzberg). The two were engaged, but Herzberg wanted to wait until the war was over to marry. The couple separated over this issue, and Albert Freytag was born out of wedlock and christened.

According to his mother his birth was a precipitate delivery. By the age of one the right side of his body was paralyzed. At 2 ½ he fell out of a window and suffered a concussion. He was vaccinated at 3 ½, and on the same day had the first episode of seizures. They increased gradually in frequency and severity. As a school-aged child he sometimes had six to eight seizures per day.

The hospital records contain comments made by Albert Freytag himself about his time in school. He attended the Königsland school in Wandsbek, which was probably a school for special-needs children. But he didn’t stay there. "The seizures kept getting in the way of reading and writing.” He was sent to the Schleswig-Hesterberg Institution when he was eight years old. There he was diagnosed with "idiocy and epilepsy.” Except for a few breaks, he spent the entirety of his short life in institutions.

The hospital records from Schleswig describe him as headstrong and forward, physically weak, and violent toward objects and other patients. His mental abilities supposedly stagnated – unsurprising as he received no encouragement or support. Nine years later, shortly before Christmas of 1933, he was released. His condition was considered "improved” since his seizures had abated under treatment.

In 1934 the "Law for the Prevention of Children with Hereditary Illnesses” went into effect. The physically handicapped and mentally ill were to be reported by doctors and medical professionals, and be examined by "hereditary health courts.” Those who did not meet their criteria for "normality” were to be forcibly sterilized. The examination board consisted of a district court judge, a government-appointed doctor, and a licensed doctor. Albert Freytag, as a patient who suffered from "idiocy” and epilepsy, was among those to whom the law applied, and he was sterilized in July 1924 in the Wandsbek general hospital. Since he was not hospitalized in the time just before the operation, it can be assumed that he was reported by a general practitioner. His epileptic seizures became more severe after the operation. By December, Freytag’s condition had evidently worsened again, as he was admitted to the Wandsbek general hospital and then transferred to the Alsterdorf Institution in January 1935. The entries in the hospital record there are similar to those from Schleswig, but make it possible to see how he viewed his own situation. He lamented his woes to his mother, "spoke of the burden that he had to bear.”

At the end of February his doctors felt he had "changed for the better.” They described him as calm, diligent and always on the lookout for work. But a few days later he had an argument with an attendant, whom he insulted in front of his mother. When he threatened the attendant with a coffee pot, he was put into solitary confinement. Every offense, no matter how trivial, was now recorded, for example his interest in newspapers, some of which he pilfered. The staff noticed that he had a tendency to hoard. He stole some tomatoes, for example, just to put them in a box. He was not aware of wrongdoing, according to the records. In 1936 he got into several fights with fellow patients. He had evidently been assigned to a work detail where he broke into a sweat at even the smallest activity, and suffered from abnormal agitation.

His limited ability to work coupled with his "violent behavior” led to a negative prognosis. In 1937, a process to have Freytag declared legally incompetent was begun. In his report, the chief physician at the Alsterdorf Institution recommended that the patient be transferred to a secure state institution. He was considered suicidal, so a permanent residency in an institution was highly recommended. Since the patient was not able to handle his affairs himself, the conditions for legal incompetence on the grounds of mental illness were met. The doctor also referred to the "family file.” In November 1924, institutions began keeping files on families with "genetic diseases,” with the goal of building up a Reich-wide "genetic health file.” Albert Freytag was evidently to be included in this file. Doctors found relatives on his father’s side of the family who had "genetic diseases” as the law defined them.

On 19 August 1937 the Wandsbek District Court confirmed Albert Freytag’s legal incapacity. A guardian was only appointed years later.

On 12 April 1938, Freytag was transferred to the Langenhorn State Mental Institution. The reason was given as: "Transfer from Alsterdorf Institution as half-Jew.” Another entry states: "The transfer occurred because Jewish patients were to be housed in state institutions.”

In Langenhorn Albert Freytag was assigned to work details in the garden or as a farmworker. This was unproductive work, and he was on one of the lower rungs of the workers’ hierarchy. In early 1939 he was fairly unproductive, and missed several days of work because of seizures. As a result he was described as an easily agitated and demented patient, who tended to aggression and made difficulties for the staff.

1939 brought dramatic changes for the patient and his family. His mother died in an accident in January. His grandmother Emma Freytag now attended to her grandson, and sometimes took him home with her. In mid-May 1940 Freytag returned from a three-week vacation, after which, in the doctors’ opinion, his condition worsened. He was transferred to another ward because he would not obey the nurses and even attacked them.

In the fall of 1939, the first steps toward authorizing the euthanasia program "Operation T4” were taken. Mentally ill patients could now be sent to extermination institutions, where they were killed in gas trucks. After protests inside and outside the country, the "Operation” directed against the mentally ill was officially ended in August 1941. 70,000 patients were victims of it. The form with Albert Freytag’s details had been sent to the "Reich Health Führer” in Berlin on 20 April 1938. The data and the five categories of patients – "unproductive,” "incurable,” and "worthless,” among others – were kept in a central file and were the basis for the euthanasia measures.

Many relatives, alarmed by the registration measures, increased their attention to the patients. Albert Freytag’s grandmother apparently tried to have Albert visit her at home as often as possible. She may have thought that a good relationship with his family might protect him from being sent away randomly. But when she requested that Albert visit her for Christmas in 1939, his doctor turned down the request.

It is striking that Albert Freytag was frequently transferred to different wards or to different institutions in the Hamburg area. The Langenhorn Instution had become overcrowded, and those mentally ill patients who had not been sent away had to make room for the physically ill, since the hospitals and homes for the elderly in the city had to be evacuated because of the danger of air raids. Jewish patients were under special observation. Since 23 September 1940, Jews were no longer placed with other mentally ill patients, but housed collectively and taken to extermination institutions. In Langenhorn, 36 Jewish women and 30 Jewish men were registered to be sent to extermination institutions.

Albert Freytag was not one of them. In March 1941 he was sent, along with 49 other men and 50 women, to an institution in Neustadt in Holstein. One week later his grandmother Emma Freytag wrote a letter to the institute’s directors asking permission to visit. She was told that she could visit the patient any time she chose.

She wrote another letter at the end of March, asking permission to take her grandson with her on vacation until 2 May, if possible, since his birthday was on 28 April. Permission was not granted, probably because another transfer was planned. Albert Freytag was sent back to Langenhorn on 3 May 1941, and then to Lüneburg on 5 May.

The repeated transfers disturbed and upset those patients who needed a regular daily routine. Each transfer also brought a worsening of living conditions and care, which had a negative effect on the patients’ health. Albert Freytag continued to suffer from mood swings – he once became agitated because he was not given his pocket watch immediately upon asking for it, and threatened to hit the doctor with a chair. The doctor’s remarks about this incident in the hospital records reveal his anti-Semitic views: "When he is irritated, it is clear that F. is a half-Jew…”.

His grandmother apparently visited him regularly. She had permission to go for walks with her grandson on the grounds of the institution, his condition permitting. Entries in the hospital record indicate that Albert Freytag was becoming more and more apathetic. He did get out of bed most days, but had little contact to others, and when the doctors did rounds, he put on a "friendly but vacant smile.” He had seizures regularly five to ten times a month, and afterwards he was irritable and stayed in bed for days.

He and 246 other patients were returned to Langenhorn on 3 September 1943. The Lüneburg institution needed the room for evacuees from homes for the elderly and ailing. At the end of 1943, the few remaining entries in the Langenhorn records describe nothing remarkable, but rather that Freytag’s behavior was calm and indifferent. Aside from the seizures, which became less frequent when the doctors began giving him the medication Luminal, Albert seemed to feel quite healthy. The doctors did notice that he was occasionally disoriented in time, which was not surprising given the uniformity of the daily routine, but he was able to say when he returned to Langenhorn from Lüneburg. Nevertheless, Albert Freytag was transferred on 1 February 1944 to the Meseritz Mental Institution, and thus approved for extermination.

Evidently the Langenhorn and the Meseritz Institutions had an understanding (until mid-1944), and Langenhorn sent a transport of 50 women from the psychiatric ward there on 25 january 1944. Shortly thereafter, on 1 February, a transport of 50 men followed. Albert Freytag was among them.

The Meseritz-Obrawalde Mental Institution was one of four institutions established between 1901 and 1904 in what was then the Prussian province of Posen (today it is Polish). The Institution was later expanded to house up to 2000 patients.

The rural location, its isolation, and the good train connections made the institution ideal for the mass murders of the euthanasia program. Meseritz became an extermination institution for "Operation T 4” in the fall of 1941, under the leadership of the Nazi activist Ferdinand Grabowski. It can be assumed that the doctors at Langenhorn knew what was going on at Meseritz. Regardless, they selected patients to be transported there, thus approving them for extermination. The death rate at Meseritz was about 90%. Langenhorn used their own staff for the transports, so than many of the attendants and nurses came into contact with the euthanasia institutions. They rode into the Meseritz Institution in the railway cars with the patients.

The transports generally arrived between 11 o’clock and midnight. Those patients who were ill or infirm were sent directly to the "death houses.” The others were distributed among the other buildings. Malnourishment, abuse at the slightest provocation and heavy labor were part of everyday life at the institution. The criteria for selection to be murdered included physical illness, reduced work productivity, misbehavior, and unwillingness to follow orders.

The murders took place in isolation chambers in Buildings 18 and 19. They were performed by the staff with medications such as Luminal (phenobarbital), morphium, and Veronal (barbital), generally administered as injections. Nearly all of the patients lived in fear, since they knew what the isolation chambers meant. The guards were armed with pistols and clubs. Patients were forbidden to have contact with anyone outside the institution, visitors were only permitted under guard. The dead were carted every morning from the buildings to the morgue. After any gold teeth were pulled, the bodies were dumped into mass graves on the institution grounds.

Albert Freytag was on the 9th transport to Meseritz. He was first housed in Building 19. He was bed-ridden, and had occasional seizures. In the next few days he was able to get out of bed, and was described as obedient and calm. He apparently tried to remain inconspicuous.

The next entry in his records was two months later. It describes frequent, severe seizures, irritability and bed-riddenness, and documented a severe seizure one day before his death. As a result of this seizure he was transferred to Building 18, where there was an isolation chamber. The last, nearly illegible entry is dated 24 April 1944. It reads "Ex(itus) let(alis) repeated seizures.” The reported cause of death was thus no different than the standard entries.

Albert Freytag was given a lethal injection four days before his 28th birthday. He died because his illness prevented him from being a productive worker and generated a high investment of care and supervision. And because doctors at the Alsterdorf and Langenhorn Institutions judged him to be "genetically sick” and selected him to be euthanised.

Wandsbek District Court records from March 1944 assumed that Albert Freytag was still in the institution in Lüneburg. It had finally appointed a (new?) guardian, an inspector from the Hamburg Social Affairs Administration, who couldn’t or wouldn’t do anything for him.

Translator: Amy Lee

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

© Astrid Louven

Quellen: StaHH 352-8/7 Staatskrankenanstalt Langenhorn Abl. 1/1995; Peter von Rönn, Entwicklung in: ders. u.a. Wege, 1993, S. 27–42, 63, 71, 72, 103, 109, 116; ders., Verlegungen in: ebd., S. 137–146; Michael Wunder, Transporte in: Peter von Rönn u.a., Wege, S. 377–379, 387, 389; ders., Spätzeit in: ebd., S. 402, 407, 420.