Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

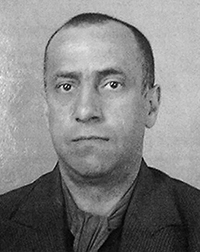

Jonny Eduard Dabelstein * 1900

Osterstraße 162 (Eimsbüttel, Eimsbüttel)

tot 26.6.1941 Bremen

Jonny Dabelstein, born on 4 Nov. 1900 in Hamburg, died on 26 June 1941 in the Bremen-Oslebshausen penitentiary

Osterstrasse 162

Jonny Dabelstein, a longshoreman, was born on 4 Nov. 1900 in Hamburg. His biological father was Johannes Friedrich Dabelstein (born on 11 July 1857 in Garding; he worked as a coachman and later as a stevedore; he died on 8 Jan. 1906 in Hamburg); his mother was Franziska, née Nabein (born on 9 July 1870 in Hamburg; no details are available about any gainful employment, and – as was common at the time – she probably managed the household). Following Johannes Friedrich Dabelstein’s death, she married Georg Zell, who thus became the stepfather of the three Dabelstein children: Jonny Dabelstein had one brother – William Robert Dabelstein (born on 15 July 1898 in Hamburg, he died there as well on 30 Jan. 1943) – and a sister – Franziska Anna Helene Dabelstein (born on 28 Mar. 1906 in Hamburg, she also died there on 28 Dec. 1962). Detlef Dietrich Dabelstein, a son of Johannes Friedrich Dabelstein outside of marriage and thus a stepbrother, was born in Hamburg on 7 Nov. 1893 in Hamburg and died in Finkenwerder on 21 Aug. 1965.

In his short life of 41 years, Jonny Dabelstein radically grappled with the social order of his day.

He pursued two activities in an attempt to improve his chances of partaking in society and, respectively, of changing the existing social order. The one was devoted to securing his material existence by participating in 1932 in selling illegally traded tobacco in Hamburg together with his wife, Elisabeth Dabelstein, in order to ensure the basis of livelihood for the family with two children. The other was the fact that in Feb. 1933, he advocated, in the political milieu of the German Communist Party (KPD), that middle-class parties in contemporary Germany be deterred from transferring political power to the Nazi party (the NSDAP). Both activities failed.

As a young person of just under 18 years, Jonny Dabelstein had volunteered as late as the last year of the war to join the imperial army. He was stationed in France with an engineer company of the 18th Engineer Battalion (Königsberg) as part of the 202nd Infantry Division. He took part in the last large-scale offensive of German troops on the western front. In the course of this campaign, his division was deployed within the context of the XXXVIIIth Reserve Corps on the Oise River from 9 to 13 June 1918. In this difficult terrain, there was in particular "a great demand for engineer formations and construction troops of any description together with the appropriate equipment.” These battles were part of the military action later described by the German side as the "great battle of France” (21 Mar. to 18 July 1918).

Before becoming entangled in these events, Jonny Dabelstein had left school in the "Selecta” – the special class of the then still seven-grade elementary schools established specifically for gifted students – of the elementary school (Volksschule) at Poolstrasse located in Hamburg’s city center. Afterwards, he had started a commercial apprenticeship at Dresdner Bank. The one year in prison that Jonny Dabelstein was sentenced to at the end of 1915 for grand larceny committed jointly with others was probably a sentence for young offenders. Additional particulars are not documented. Furthermore, what subsequently brought him in contact with the military jurisdiction in Strasbourg during his time in the army – in this case, he was accused of "crossing a blocking line without authorization” – cannot be reconstructed from the records; however, on 18 Mar. 1918, it earned him a three-day prison term passed by the court martial in Strasbourg.

Many of the returning soldiers had become "war disabled,” while others carried the scars of war with them visibly and invisibly. In the case of Jonny Dabelstein, the column "distinguishing marks” on the prison card file, which would accompany him all his life, read "gunshot scar on the wrist.”

"In 1918, having returned from the battlefield, I was employed as a worker by a number of companies,” read a passage from a curriculum vitae written by Jonny Dabelstein in 1935, which lacks any clue as to whether he had participated in the political conflicts in 1918 or whether perhaps he had already become active in the political left at this time (in 1922, he became a member of the German Communist Party, the KPD).

After the war, two crimes committed in short succession in 1920 (burglary and grand larceny attempted jointly with others) earned him three years and three months in prison as well as the loss of his civil rights for six years. A "second offense of grand larceny,” committed in the crisis year of 1923 immediately after his release, made the penalty more severe: The court now imposed a sentence in a penitentiary (two years and the loss of civil rights for three years); in addition to the remainder of a sentence still to be served, he stayed in prison until 22 June 1926.

When he was released, the times continued to be marked by social upheaval, in which large parts of the population became entangled. In this period, he also met his later life companion, the worker Elisabeth Flaegel (born on 3 June 1903 in Gadebusch near Schwerin; died on 18 Aug. 1982 in Hamburg). They decided to get married, and the wedding took place on 5 Oct. 1929 (son Rolf had already been born on 31 Aug. 1928; daughter Edith was born on 17 Sept. 1930).

In the family records, a photograph, taken before they were married, turned up that shows Jonny Dabelstein and a girl aged three or four years. The girl stands in familiar closeness to the left of him, with her hand in his: Karla. She was his daughter from an earlier non-marital relationship. Today, there is no longer any information available in the family about the course her life may have taken; apparently, Karla fell ill with diphtheria and died early.

Perhaps Jonny and Elisabeth Dabelstein still pursued gainful employment in the years they met. When in 1932 they participated in selling tobacco smuggled from the Netherlands in Hamburg, they were already registered again as being unemployed. These tobacco sales without revenue stamp were based on a sophisticated organization. The people involved in it as intermediaries and end users were primarily unemployed persons who frequently came across each other at the Hamburg employment office and constituted an assured circle of purchasers for the cheap tobacco, whereas procuring the goods tended to be in the hands of professionals. They had to pay a certain sum of money in order to receive the merchandise in Cologne from persons maintaining direct contact with tobacco smugglers from the Netherlands. Subsequently, the goods found their way to the Hamburg distributors on a variety of channels. In one scenario, the merchandise was picked up using rented cars; sometimes a motorcyclist (Thomas R., the brother-in-law of Jonny Dabelstein, also a worker and active in the Alliance of Red Front Fighters [Roter Frontkämpferbund – RFB] like the latter) with a sidecar (and Jonny Dabelstein as the sidecar passenger) was also on the road to Cologne, and sometimes it happened that the skillfully packaged goods, once arrived in Hamburg, were pushed on a Scotch cart from a garage serving as a temporary storage through the streets of Hamburg to the distribution point. Alternatively, the merchandise was shipped by railroad express using falsely declared waybills. This represented a risky way of transportation since the customs investigation department, concerned with losing tax revenues, was not idle. Railroad employees passed on their observations, for instance, when a crate declared as a shipment of fittings seemed to them too light, or when persons indicated as recipients of those crates shipped as rail freight aroused their suspicions when having the crates loaded on their "Tempo” three-wheeled car.

On 17 June 1932, the customs investigation department struck, arresting Jonny Dabelstein and others, as they were busy distributing tobacco. The customs officers had become aware of a truck just having arrived "from the west in Hamburg,” loaded with approx. 10 hundredweight of tobacco. In this case, the merchandise had been stored in a room at Luruper Weg 63 for further distribution (with Walter D., a party member of Jonny Dabelstein) and had to be sold within only a few hours. In the process, Jonny Dabelstein’s apartment at Osterstrasse 162, back yard, house no. 2 ground floor, served as a contact address. From there, he went with the purchasers he knew or that had been procured by other means to Luruper Weg; afterwards, he took care of directly handing over the money, outside the apartment, to the person who had advanced the funds (and who insisted on checking personally how the sale went). There was something left over for everyone involved in the deal; also for Jonny Dabelstein, who, when arrested together with three others, "[was] just in the process of counting and placing tobacco into a suitcase” – Dutch Dobbelmann tobacco. On this score, he stated during his first interrogation: "Naturally, word that tobacco was available got out very rapidly among those interested at the employment office. Obviously, I do not know the purchasers by name. The merchandise went quickly in batches of five or ten pounds. I probably sold about 60 pounds […].”

Elisabeth Dabelstein also participated in the distribution. Acting as a messenger and informer in the context of the small-scale distribution, she had been the one to come in contact with the tobacco dealers in the first place; Jonny Dabelstein then took on the trips for procurement to Cologne and the intermediate trade in Hamburg. In Hamburg, more than 30 persons overall suspected of tobacco purchases and thus of handling tax-evaded goods were arrested and interrogated in connection with what the public prosecutor’s office called the "Dabelstein et al.” ("Dabelstein u. a.”) matter; many of them were unemployed. For some of them, the criminal record indicated – minor – property crimes. Others were suspected of handling stolen goods on a professional basis; through the information gathered from them, eventually an extensive ring of smugglers and dealers in stolen goods was broken up in the Rhineland.

After his provisional arrest, Jonny Dabelstein was in pretrial detention until 30 June 1932. Like the other accused, he confessed as well; Elisabeth Dabelstein also provided a detailed record of interrogation. In the aftermath, the public prosecutor’s office pursued further investigations; it was very keen to break up the actual ring of dealers in stolen goods, whose location it suspected to be in Cologne. Therefore, Jonny Dabelstein and others were not yet charged in 1932.

On 30 Jan. 1933, Hitler, supported by the bourgeois parties of the right, had been charged the by Reich President with forming the new government; since that time, marches of the SA and other Nazi organizations dominated the street scene, and they did so in Hamburg as well.

The RFB planned a series of attacks on SA members and meeting places, which, after commands and weapons had been issued at the Stephanus Church, were carried out in Lutterothstrasse and in Stellinger Weg on 26 Feb.; as subsequent police investigations revealed, an attack on an SA march was planned as well. In this case, the intention was to throw bombs at the very moment this parade would have come in close vicinity of a demonstration by the [Social Democratic] Banner of the Reich (Reichsbanner) taking place simultaneously, thus inciting a violent confrontation.

However, after the Reichstag elections on 5 Mar. 1933, though not yielding to the Nazi party the absolute majority it had expected but nevertheless a sufficient majority in the alliance of the bourgeois "black-white-red” conglomerate to form a government, the state machinery came under Nazi control. At the same time, coalition talks took place in Hamburg. As early as 6 Mar. 1933, the Reich Commissar and new head of police in Hamburg, Alfred Richter, had police, assisted by participating special units raised ad hoc (the Commando for Special Use [Kommando z.b.V.]), fan out to make the first arrests of political opponents; those arrested also included Jonny Dabelstein.

He was placed in pretrial detention on 7 Mar. 1933. There is no record as to how his arrest came about. The interrogations at the Hamburg police prison, the Stadthaus, were marked by extreme brutality. Not everyone managed to bear up against them, which meant information was passed on. Subsequently, it also became known that the party apparatus of the KPD was infiltrated with political turncoats and informers. The fact that in his application for restitution, Dabelstein’s son Rolf later, in 1947, indicated that in the course of his father’s arrest, not only political things were confiscated but also the family’s radio set suggests that a house search took place. Together with others, Jonny Dabelstein was accused of having participated in those assaults on SA men and the planned bomb attack on the SA demonstration march in Eimsbüttel on 26 Feb. 1933.

In both cases, he was charged before the Hanseatic special court (Hanseatisches Sondergericht) for, among other things, breach of the public peace and membership in the RFB and convicted on 16 Feb. and 21 Feb. 1934, respectively. In the course of the first proceedings – presided over by Dr. Rüther, whom the contemporary press reported to be "one of the foremost among National Socialists in Hamburg” – the court pleaded for "an overall sentence of ten years in prison and the loss of civil rights for eight years for jointly attempted murder, breach of the public peace, etc.” (‘Sond. 1576.33 Kripke u. a.’); in the second proceedings, the bomb trial (‘Sond. 1577.33 Wüpper u. a.’), the first penalty was combined with the new sentence, and Jonny was convicted to serve a total prison term of 14 years with loss of civil rights for ten years.

The case files are not available in Hamburg or only in excerpts; however, in the restitution proceedings initiated by his children after 1945, the short form of the sentences passed at the time including the court’s opinions is cited from a plea for clemency submitted by Jonny Dabelstein, for which a clemency file was started. One passage reads:

"On 26 Feb. 1933, at the behest of the RFB leadership, systematic armed attacks were conducted in Hamburg on SA men on their way to their assembly points. For instance, on the SA men Jahns and Zander, several pistol shots were fired, all of which missed their targets. The convicted [Jonny D.] was organizational head in this unit, leading the attacks in question here. He handed one of the gunmen his pistol, instructed him in how to use it, and gave the groups of gunmen the order ‘to shoot down’ SA men. (XI Sond. 1576/33; §§ 211, 43, 74 StGB),” and: "According to the plans of the RFB, 26 Feb. 1933 was to see a bomb attack on an SA march in Hamburg. The plan did not come to fruition because the SA march and an SPD march, upon whose meeting the bombs were to be thrown, marched at too great a distance from each other. The convicted [Jonny Dabelstein] was the organizational head of the unit designated for the attack, staying together with the head of the unit in the apartment of a Communist near the crime scene. He learned of the plan there and stood by at the ready until the operation was aborted. (XI Sond. 1577/33; § 6 des Sprengstoffgesetzes [law on explosives]).”

For Jonny Dabelstein, the first conviction meant that he had already begun serving his hard prison sentence. He remained in the Fuhlsbüttel penitentiary until 1939. On 6 Apr. 1939, he was transferred to Bremen-Oslebshausen. The registration card of the Hamburg penal institutions noted the end of the prison term (calculated against the pretrial detention) as 7 Mar. 1947. His release was to take place on that date at 10 a.m. However, before then, the matter still up for clarification was tobacco trading in conjunction with handling tax-evaded goods, charges for which he and 30 other defendants had to stand trial before the Regional Court (Landgericht) in Hamburg. On 16 Oct. 1934, the "Grand Criminal Chamber” (Grosse Strafkammer) presided over by Judge von Döhren ordered opening a trial in connection with these legal proceedings; however, it took several months before the actual trial began. The sentence was passed on 3 Apr. 1935.

For Jonny Dabelstein, it resulted in the stay of proceedings pursuant to Sec. 154 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Strafprozessordnung – StPO) (according to this section of the Code of Criminal Procedure, it was possible to refrain from bringing charges if the punishment the accused would receive for an offense did "not make a difference” if that person had already been convicted in another criminal trial – in the case of Jonny Dabelstein, in his trial for high treason). Elisabeth Dabelstein was supposed to pay an extra 92,000 RM (reichsmark) in evaded taxes and go to prison for two weeks. In both cases – as in the case of most other accused – the court assumed the existence of a desperate economic situation that determined their actions. Following a plea for clemency, which the Reich Minster of Finance approved on 19 July 1935, Elisabeth Dabelstein succeeded in having her penalty waived subject to good conduct, for period extending until 1 Aug. 1938.

On 30 Nov. 1938, Elisabeth Dabelstein got divorced from her husband; she had already moved out of their joint apartment on Osterstrasse and moved to Valentinskamp 44, house b/fourth floor. Later, she remarried and her subsequent married name was Elisabeth M. When the children filed applications for "restitution” after 1945 – the issue was support questions and compensation for the term of imprisonment suffered by their father – she waived all of her claims in favor of the children. She died in Hamburg on 18 Aug. 1982.

Jonny Dabelstein began serving his sentence in the Fuhlsbüttel prison. Even during his pretrial detention, he had been kept in solitary confinement for the most part. On 3 June 1933, his wife did request that her husband, "Jonni Dabelstein [...] be released from solitary confinement” on the grounds that she "felt during the last visit on 29 May 1933 that my husband was at the brink of a nervous breakdown. In order to prevent the old ailment from surfacing again, which caused my husband to spend time at the Friedrichsberg sanatorium in 1922 and 1926, I would thus ask Messrs. Investigating Judges to transfer my husband from solitary confinement to [the] group confinement and, above all, to make available mail to my husband as soon as possible.”

For a while, Jonny Dabelstein was assigned a cellmate, but on 27 Aug. 1939, he wrote to his family:

"Yes, Lene [i.e. his sister Helene], I am still in solitary confinement and have no hope of things ever changing. It is not conceivable for all of you just what that means. Not being able to have a talk at all for six and a half years, and now that same period over again. And then what? Concentration camp? All of this is inconceivable – only the children and mother keep me hanging on. I would like to be allowed to work physically, hard physical labor, as that would be a relief. The nights are so horribly long.”

Towards the end of his time in the Fuhlsbüttel penitentiary, Jonny Dabelstein worked as a weaver. He received good assessments for his work. Responding to the question in the conduct report whether "hope of improvement [exists],” the institution’s foreman indicated: "there is the possibility.” The administration added, "Dabelstein continues to struggle toward coming to his senses (receives book on racial issues)” – Jonny Dabelstein seemed to grapple with questions of Nazi ideology. However, that the character of National Socialism appeared unchanged to him and implied war emerged from a letter to his parents dated 27 Aug. 1939, when– addressed to his mother – he expressed his fears there:

"[D]ear Mother, how do you feel these days? You are becoming quite old. Experienced [the wars of] ‘70 –‘71, ‘14–’18 – and now perhaps all over again? I don’t believe so, since it would indeed be horrible.–”

He knew what war meant. Only a few days after his letter, German troops invaded Poland. His mother had to live through yet another war (she died at a very old age, nearly 85, in Hamburg on 11 May 1955).

When he wrote the above letter, Jonny Dabelstein had already been transferred from the Fuhlsbüttel penitentiary to the Bremen-Oslebshausen penitentiary. At the time, Oslebshausen, which in the context of the North West German penal system of penitentiaries also had jurisdiction over Hamburg, was still headed by its director Werner Wegener, in office for five years by then; he was a member of the NSDAP and belonged to the SA – and he was a bearer of the Golden Party Badge of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, a decoration awarded only for long-standing membership. He had assumed his new office on 12 Mar. 1933, shortly after political power was handed over to the Nazis in Bremen. Later – Werner Wegener had volunteered to join the Wehrmacht in Sept. 1939 – the police inspector Otto Wegner succeeded to the post of institutional director. The inmates described him – nicknamed "Nero” – as a "brutal figure,” feared because of his mania for punishment.

Due to the numerous political trials, the detention facilities were overcrowded in 1933 and the years following; in Oslebshausen, the number of detainees had risen to more than 2,000 by 1937, which meant the designated maximum occupancy had more than doubled. In a wave of frantic activity, supervisory staff had welded together iron beds and set them up in one of the church rooms in the institution in order to cope with the flood of prisoners. Even if Jonny Dabelstein was not affected directly by these difficulties to accommodate inmates because he was in solitary confinement, the altered organization of the institution did have an effect on his life there. This concerned the discharge of duties by supervisory staff, institutional work, nutrition of the prison inmates, and – something that would become a matter of survival for him – medical care. The situation became worse for him because starting in 1938, the inmates of penitentiaries were included in the [forced] labor deployment program across the Reich.

Jonny Dabelstein was forced to dig peat in the bogs neighboring the penitentiary (the Oslebshausen penitentiary maintained an external labor camp in the bog near Strückhausen).

The "external gangs,” as the labor duties outside the penitentiary were called, were guarded by untrained personnel: members of the police reserve of the Bremen police battalion but also staff of the private Security and Guard Service (Schutz- und Wachdienst) (Hamburg) and of guard services operated by private firms, respectively.

In the Dabelstein family, information has been passed down that during one of these external work details, Jonny caught sight of his brother William, who had also been sentenced for political activities. Spontaneously, he apparently tried to draw attention to himself across the distance by loud yelling, upon which one of the guards hit him on the head with the butt of his rifle. Since then, he felt unwell and ill, undergoing medical treatment.

Years earlier, even the director of the institution, Werner Wegener, had criticized the inadequate health care and nursing at the penitentiary. "The institutional hospital was established,” he wrote in a report in 1936, "when the facility had 400 prisoners” – now, he added, it had 1,200 inmates. The effect was, he went on, that patients had to be cared for in a makeshift fashion, lying on mattresses or bags filled with straw on the ground, some of them even at a distance from the actual infirmary. He applied for construction of a new infirmary appropriate to the situation – a project not realized, however, in the period before the war. Another inadequate feature was the nutritional situation of the prisoners. If they were not supplied with sufficient food even in peacetime, the dietary conditions increasingly deteriorated even more during the war. In 1942, the institutional physician reported on the insufficient nutrition of the prisoners detained at Oslebshausen. On 10 Aug. 1942, he filed a report complaining about symptoms of malnutrition. Amidst this situation, the seriously ill Jonny Dabelstein fought for survival.

Three medical reports provide an idea about his suffering: According to this, he had "[complained] since early June 1941 […] about earaches on the right ear and therefore underwent treatment by the doctor doing the rounds. On 10 June 1941, Dabelstein then collapsed while working on an external gang and immediately afterwards was transported to the hospital at Oslebshausen.” Reportedly, he was operated the following day, but then "died […] on 26 June of meningitis and a brain abscess caused by the ear complaint and further effects of the ear disease.”

Scrutinizing the validity of these medical certificates is no longer possible today.

Jonny Dabelstein’s son, Rolf Friedrich Dabelstein, who after 1945 grappled with his father’s life story and improved his occupational situation from machine fitter all the way to master of vessels upon inland and near coastal waters, died on 18 May 1999.

The latter’s son, in turn – Jonny Dabelstein’s grandson – Werner Dabelstein, has documented the family history; today he lives – married to wife Birgit – in Kaltenkirchen.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

© Peter Offenborn

Quellen: StAH 213-11 Staatsanwaltschaft Landgericht – Strafakten L 0010/37 Band 1 bis 4; StAH 242-1 II Gefängnisverwaltung II, Abl. 12, Nr. 81; StAH 242-1 II Gefängnisverwaltung II, Abl. 13 (ältere Kartei); StAH 351-11 AfW 23044; Ab.; Informationen der KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme; Sammlung VVN-BdA (Hamburg); Der Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Berlin 1944 (hg. vom Bundesarchiv 1956), S. 331 und 397f.; Ludwig Eiber, Arbeiter und Arbeiterbewegung, S. 195–203; Hans-Robert Buck, Der kommunistische Widerstand, S. 37; Wolfgang Michalka, Das Dritte Reich, S. 694–775; Die Strafprozessordnung für das Deutsche Reich vom 22.3.1924 (Ewald Löwe); Hartwig Fiege, Geschichte der hamburgischen Volksschule, S. 45 und 62; Nikolaus Wachsmann, Gefangen unter Hitler, S. 90/91; Hans-Joachim Kruse, Zur Geschichte des Bremer Gefängniswesens, S. 76f., 101, 148, 160/161; Hamburger Tageblatt 5 (1933), Nr. 114 (17.5.), S. 7; Informationen der Familie von Werner Dabelstein (Oktober 2010).