Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

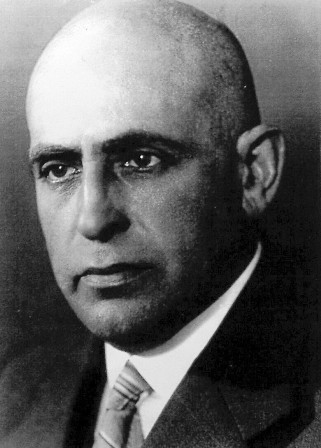

Robert Liebermann * 1883

Im Alten Dorfe 61 (Wandsbek, Volksdorf)

HIER LEBTE

ROBERT LIEBERMANN

1919 – 1941

GEDEMÜTIGT / ENTRECHTET

Robert Salomon Liebermann, born 05/22/1883, evicted from here in 1941, died 1966

Usually, Stumbling Stones remind us of people who were murdered in the Nazi era or "voluntarily” ended their own lives. In Exceptional cases, however, the artist Gunter Demnig also lays stones for persons who had to endure a special ordeal, as here for Robert Liebermann.

In 1917, the Hamburg banker Friedrich Salomon Liebermann bought the property with the address "Im Alten Dorfe 61” in the village of Volksdorf with the present Jugendstil villa built in 1912.

His son Robert studied machine engineering in Munich at the beginning of the century and took part in the First World War as an artillery officer. For special merits, he received several decorations that meant a lot to him. During a stay in a military hospital, he met the nurse Annemarie Stampe (* 1893); the couple married and moved into Robert’s parents’ villa in Volksdorf with their son Rolf, born 1919.

Robert and Annemarie Liebermann felt themselves securely rooted in their Fatherland. The fact that the widely ramified family included such illustrious names as the painter Max Liebermann (1847–1935) and the composer and future opera house director Rolf Liebermann (1910– 1999) may have contributed to their firm conviction.

In the middle of the 1930s, there was rioting and shouting in front of the Liebermanns’ villa. The mob in brown uniforms intruded into the house, ripped books from the shelves and devastated the library.

In 1931, Robert Liebermann had lost his livelihood, because the Cochu tinware manufacturing company, of which he had been the director since 1913, went bankrupt. For him as a Jew, it was impossible to get an adequate job after the Nazis came to power in 1933. The Liebermanns suffered financial difficulties and in 1935 were forced to let the flat on the ground floor to a family. A ray of hope: Dr. Thilo, the new tenant, stood by the Liebermanns. When the Gestapo came at night to search the house, he also got up and made it clear to the intruders that he disapproved of their doings.

In November, 1938, Robert Liebermann found himself in "protective custody” at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. On account of a Himmler decree, prisoners over 50 years of age were released after a few weeks. They had, however, to fear "consequences” if they dropped even a hint about their experiences at the concentration camp to people outside. Robert Liebermann kept his commitment to silence.

In the meantime, the community in the villa had changed: Jewish families stayed with the Liebermanns while they waited for their emigration to England. Robert Liebermann had established a sort of boarding-house. The children were given private lessons and also socialized with the kids in the neighborhood. To their regret, however, the playmates regularly were gone as suddenly as they had previously appeared.

Ingeborg Hecht, a Hamburg city child who spent several summer vacations with the Liebermanns, recalls: "We had to do light gardening jobs and clean vegetables, because Aunt Anni ran a strict regime, whereas Robert only tried to instill his enthusiasm for nature into us.”

Rolf, the Liebermanns’ only child of their own, in Nazi terminology a "Mischling of the first degree”, attended the elite "Johanneum” high school in the city. After graduating, he wanted to protect his Jewish father by immediately volunteering for military service. But, in the thinking of the Nazis, Rolf as a "half-Jew” was not good enough, indeed "unworthy to do military service” Thus, Rolf began an apprenticeship as an aircraft builder. When he brilliantly passed the final exam, the family made a new effort to have Rolf declared "worthy to do military service”, also tapping relations: to Carl Vincent Krogmann, the first Nazi Mayor of Hamburg, and to Hermann Göring’s Hamburg father-in-law Sonnemann. With success: (fair-haired) Rolf Liebermann was declared a "valuable member of the German nation, and thus ‘equal to people of German blood’, so that he probably would have been able to study. In spite of this, he joined the Hamburg infantry regiment no. 76 as ensign-sergeant – with fatal consequences.

On May 16th, 1942, Robert Liebermann wrote from Hamburg to the Ahlenfelds, friends in Berlin:

"Dear Erich, dear Sabine,

Great grief has stricken us. Our boy, our one and all, has fallen. Yesterday, we received the message from his company commander. On April 25th, he was leading a reconnaissance patrol and was shot on the head; he did not suffer. Our only hope, the purpose in our life has been destroyed.”

In the meantime, Rolf’s parents remained largely spared from harassment in their villa.

Since January 1st, 1939, all Jews were forced to bear the middle name Israel (women: Sara) Robert Liebermann refused, which brought him several weeks of "protective custody” in the Fuhlsbüttel Police prison at the beginning of 1941.

That same year, the City of Hamburg began to pressure Jewish real estate owners to sell their property to the City far below its actual value. To avoid this, Robert Liebermann tried to transfer the villa with its land to Rolf’s ownership. However, Liebermann’s application failed because the Borough of Volksdorf had cast an eye on the property "Im Alten Dorfe 61.” The Liebermanns moved out within the year; they had received a fraction of the price Robert’s father had paid in 1917. 7,500 RM of the proceeds were deposited in the blocked account "Robert Israel Liebermann” as "Reich Flight Tax.”

From May, 1943 to May, 1945, Liebermann’s "work book” shows that he had to perform forced labor for a wholesale shoe company in the city, where he worked at building sites and hauled crates. Liebermann and his wife now lived in Hummelsbüttel. As Jews had only very limited access to public transport, Robert, now 60 years old, had to walk to work and back – a total of six hours per day.

After the war, the Liebermanns were offered the restitution of the property Im Alten Dorfe 61. However, considering all that had happened, they preferred not to return, and were "indemnified” with a house in Volksdorfer Damm, but chose to live in Sarenweg in the borough of Ohlstedt.

Until the end of their lives, Robert and Annemarie Liebermann kept in contact with Eva Löwenthal, the girl friend of their son who had managed to emigrate to England in 1938. Even later, as the married Eva Scott, she visited Rolf’s parents every year at Christmas. Robert Liebermann lived until 1966. After Annemarie Liebermann’s death in 1987, Eva Scott cleared out the Liebermanns’ household. Annemarie and Robert’s grave is in the Ohlsdorf cemetery. It was to be cleared in 1912.

Although the house "Im Alten Dorfe 61” had belonged to the City of Hamburg since 1941, and used as a police bureau until the beginning of 1908, the people in Volksdorf still call it the "Liebermann Villa.” In 1912, the architect Gerhard Nickel bought the prominent historic property and since has since painstakingly restored it to its original beauty, to the delight of the neighbors, who cultivate the memory of the family who was disenfranchised and displaced from here.

Translated by Peter Hubschmid

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: March 2017

© Ursula Pietsch

Quellen: AFW, Aktennr.220583; Regina Scheer, Liebermanns, S. 387; Pietsch, Volksdorfer Schicksale, in: Unsere Heimat die Walddörfer, Nr.4/2004, S. 47; Briefe von Rolf, Annemarie und Robert Liebermann an Familie Alenfeld; Interviews mit Ingeborg Hecht, Renate Thilo, Henry Hartjen 2003–2006.