Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

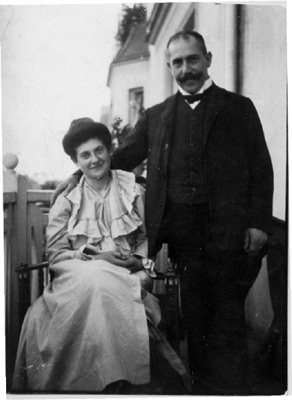

Magarete Windmüller (née Simon) * 1883

Dorotheenstraße 43 (Hamburg-Nord, Winterhude)

1940 Anstalt Berlin-Buch

ermordet 11.03.1941

Margarethe Windmüller, née Simon, born 11 Mar. 1883 in Hamburg, died on 11 Mar. 1941 in the "Berlin-Buch sanatorium and nursing home” ("Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Berlin-Buch”)

Margarethe Windmüller, a völkische activist, craftswoman, and travelling journalist, had a strongly developed sense of self-confidence. She came from a wealthy Jewish merchant family and was herself baptized a Protestant. Her parents were Carl Jacob Simon (born in 1850) and Rosa Gabriele, née Seckels (born in 1860). Her father co-owned the Carl Simon & Mayer import and export company in the Sternhof at Hohe Bleichen 9.

Margarethe Simon was born in Hamburg on 11 Mar. 1883, one year after her sister Erna. Her sister Paula was born on 17 Nov. 1886 and her brother Philipp on 28 Dec. 1890. The family lived at Harvestehuderweg 63.

We can assume that Margarethe Simon received the education of a "daughter from a wealthy family” ("höhere Tochter”). At the age of 18, she married the dentist Dr. Percival Sidney Windmüller (born on 25 July 1865 in New York, see Stolpersteine in Hamburg-Hamm), also of Jewish origin and baptized a Protestant. The couple moved to Hagedornstrasse 25, where their son Kurt was born in 1903. In the following year, they acquired the property at Hochallee 57 featuring a beautiful Art Nouveau house. There, Margarethe Windmüller found a field of activity for her artistic talent and established an arts and crafts workshop. In addition to his professional activities, her husband spent a lot of time doing research in dentistry. He also invested a lot of effort in making music. On 21 Dec. 1904, daughter Lilly was born, on 1 Oct. 1911 Harald, who later called himself Denny. The youngest, Henning, was born on 25 May 1913.

However, Margarethe Windmüller obviously did not feel happy. In 1916, she attempted to commit suicide. A few years later, around 1925, their marriage was divorced. The eldest son had died in July 1918 at the age of only 15. Daughter Lilly had completed training as an infant and monthly nurse; she lived in the homes of her respective employers. But Harald and Henning still went to school when Margarethe Windmüller moved to Dorotheenstrasse 43 in the Winterhude quarter.

The two underage sons were looked after – as before – by the female housekeeper and cook in their father’s household. According to Henning, their father took care of them "in a touching way,” but the only day left for this was Sunday.

Margarethe Windmüller was involved in the "Nordic Society” ("Nordische Gesellschaft”). Founded in 1921, this association wanted to foster the "Nordic idea in Germany and countries of the North related by tribal bonds.” There, she met well-known people, from Prof. Mendelsohn-Bartholdy to Karl Kaufmann, the [subsequent Hamburg Nazi] Reich Governor (Reichsstatthalter). Margarethe Windmüller by then worked as a self-employed craftswoman, photographer, and journalist. Love of beauty and nature on the one hand and national interest on the other led her to travel and write for the "German Foreign Institute” (Deutsches Auslands-Institut – DAI) in Stuttgart (forerunner of the Goethe Institute) and the "Nordic Society.” She also published in the Swedish, Finnish, and Danish press. At times, she lived in Finland but kept her apartment at 43 Dorotheenstrasse in Winterhude.

The "Nordic Society” and the Foreign Institute aimed at improving cultural and economic relations with foreign countries, and though they had a völkische orientation, they were not anti-Semitic. In 1937, however, the Nordic Society excluded the "non-Aryan” members. Margarethe Windmüller seems to have continued her work though, perhaps under the protection of Executive Secretary Schnaas, or perhaps the persons in charge did not associate her pseudonym Sundström with Margarethe Windmüller the person.

Although a "full Jewess” ("Volljüdin”) according to the Nazis’ "racial” classification, she believed, due to her merits in the national movement and her pioneering ideas, not only to be exempt from the reprisals against Jews, but also to be able to continue to participate in reflections on Germany’s future. She knew the northern regions of Scandinavia well from her own experience. Yet not only the landscape and nature fascinated her, but she also looked at the regions from the point of view of German raw material interests and German war planning. At the beginning of Sept. 1939, she wrote to an undersecretary (Ministerialrat) in Berlin, proposing the "expansion of the Arctic Ocean Highway [Eismeerstrasse] for ore transport to ‘Germany’ [translator’s note: English term used in the German original]” and pointing out that she had long discussed this project, "highly interesting strategically-geographically and probably also under the aspect of war” with Nazis who were close to the ‘Nordic Work.’ She had "dared” to write that letter, since she was "certainly the first person in Germany to come up with this ingenious idea through in-depth expertise.” An underlying issue in her considerations was the fact that the sea route to the Swedish iron ore reserves in Kiruna, which the German armaments industry needed, had become too unsafe due to the beginning of the Second World War. As an alternative, she proposed to use an Arctic Ocean Highway for the supply of ore, or perhaps to expand it. Such a proposal might definitely have been in the interest of the warring German Reich. Perhaps it would have been impossible to finance or not practicable for other reasons, but in effect, it never became the subject of serious consultation with its advocate, instead overlapping with her arrest.

Margarethe Windmüller was taken into "protective custody” ("Schutzhaft”) on 12 Sept. 1939. The reasons for the detention are not clear. She was supposed to have illegally photographed guns and was accused of "racial defilement” ("Rassenschande”). Family members reported that she was very extravagant and full of joie de vivre, so that she may have aroused suspicion and been denounced because of her non-conformist lifestyle.

Margarethe Windmüller herself assumed political reasons for her arrest and insisted that she belonged in the Fuhlsbüttel police prison. Instead, she was committed to a psychiatric ward. Outraged, she wrote to the psychiatrists about her Arctic Ocean Highway proposal: "Since I had fought for many years from Finland (partly in the context of the ‘Nordic Society’) like a lion for many things that would be favorable to my homeland (in the case of war) – and many things had also been published, just as I had been in contact with the naval authorities (the case of the Aland Islands...) for years, among other things for this reason – I could afford to make this suggestion, despite being a non-Aryan. Since I was allowed to supply the Scandinavian, Finnish, and English press under the name of Sundström until the outbreak of the war, my reputation as a logically thinking journalist is quite clear. (For information, [please refer to] Pg. [Parteigenosse = party comrade] Eugen Schnaas c/o ‘Nordic Society,’ Dammtorstrasse 14).”

However, the psychiatrist who examined Margarethe Windmüller the day after her arrest considered the possibility of an Arctic Ocean Highway delusional and referred her to the psychiatric hospital in Friedrichsberg. From there, she was transferred to the Langenhorn "sanatorium and nursing home” ("Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Langenhorn”) on 28 Sept. 1939. The diagnosis was: "Hyperthymic querulousness, paranoid reinterpretations.”

The doctors did not go into the content of her proposal at all, but diagnosed her with paranoid exaggerations, among other things because of this idea, but at the same time attested to her unimpaired intelligence and admitted that some things in her narratives were based on truth. That she, being a "non-Aryan,” was not to expect any help in this connection did not enter her mind.

When an article on the Soviet Union’s Finland policy appeared in the Hamburger Tageblatt on 1 Nov. 1939, accompanied by a sketch of Scandinavia with the Arctic Ocean Highway, Margarethe Windmüller wrote to her sister Paula that this was a drawing she had made, that she had attached it to the letter dated Sept. 1939 to the undersecretary mentioned earlier. She felt rehabilitated. The doctors, on the other hand, were rather encouraged in their diagnosis that she was suffering from delusions. Margarethe Windmüller was not discharged, especially since, according to her medical record, she often showed herself to be a difficult patient who talked a lot and pointed out a new illness every day. The doctors diagnosed an orbital tumor (tumor of the optic nerve) and considered that this was the cause of her personality change, but then rejected this explanation and all possible therapies as well. A "legal adviser” ("Konsulent”) [a newly introduced Nazi term for Jewish lawyers banned from full legal practice] commissioned by her tried in vain to ensure that the operation she desired would be carried out.

Apparently, Margarethe Windmüller never asked to be discharged home. She had moved to Horn, at Kroogblöcke 10, in 1938, into an apartment from a maternal inheritance. This was far away from Isestrasse, where her son Harald/Denny and her daughter-in-law, Mathel, née Kohn, from Vienna, lived.

Margarethe Windmüller did not acknowledge the identity as a Jewess assigned to her; it was not until 1940 that she became a member of the Jewish Religious Organization (Jüdischer Religionsverband).

She received interpersonal support from her sister Paula Rehtz and, during her occasional visits, from her sister Erna Stavenhagen from Berlin.

Exactly one year after her committal to the Langenhorn "sanatorium and nursing home,” she was transferred to the Berlin-Buch "sanatorium and nursing home.” We do not know what happened to her in the last six months, nor whether her death was caused by medication or neglect.

Margarethe Windmüller’s father, Carl Jacob Simon, died on 2 Dec. 1933, and his widow moved to an apartment at Alte Rabenstrasse 34 and from there to Grasweg 32, where she lived on the fortune that her husband had left her.

In 1933, Margarethe Windmüller’s son Henning could no longer realize his wish to study medicine like his father had done. Instead, he took on an apprenticeship as a shipping company clerk and completed two internships in Finland. He was drawn to this country, like his mother had been before him. Later, he went back to Finland as a war volunteer and stayed there after the war.

After Margarethe Windmüller’s death, her daughter Lilly inherited one third and her son Harald two thirds of the estate, which essentially consisted of mortgages. Son Henning in Finland was not considered. In 1949, his aunt Paula Rehtz, who survived the deportation to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, sent him a list of the names of the murdered family members to Finland: Dr. Percival Windmüller and his second wife, Gertrud, née Friedländer, died in Theresienstadt. The traces of Henning Windmüller’s siblings were lost in the Lodz Ghetto, those of his aunt Erna in Riga.

Despite his great longing for Hamburg, Henning Windmüller did not return to Germany; in his interest for Finland, he knew himself connected to his mother.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: May 2019

© Hildegard Thevs

Quellen: 1; 2 ZK 28/391; 4; 5; StaHH 135-1 Staatliche Pressestelle I –IV, 4575, 4576, 4595; StaHH 352-8/7 Langenhorn, Abl. 1, 1995, 26469; Landesarchiv Berlin, ARep 003-04-01 Nr. 21998 (Aufnahmebuch HPA Buch), Nr. 115 (Verlegungslisten), Nr. 162 (Abrechnungslisten), dankenswerter Weise von Dr. Hannelore Dege 2017 erforscht und zur Verfügung gestellt; StaHH 522-1, Jüdische Gemeinden, 992 e 2 Deportationslisten Bd. 1 und 5; Ev.-luth. Kirche St. Johannis, Hamburg-Harvestehude, Taufregister 1914; Stadtarchiv Lübeck, Vereine und Verbände, Nordische Gesellschaft, Akte des WWI Kiel, 1924–1944, 3; Ernst Ritter, Das Deutsche Auslands-Institut in Stuttgart 1917–1945, Frankfurter Historische Abhandlungen, Band 14, Wiesbaden 1976; Kaja Barche, Die Konversion von Margarethe Windmüller. Geschichtswettbewerb des Bundespräsidenten 2017 "Gott und die Welt"; persönliche Mitteilungen von Angehörigen.

Zur Nummerierung häufig genutzter Quellen siehe Link "Recherche und Quellen".