Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

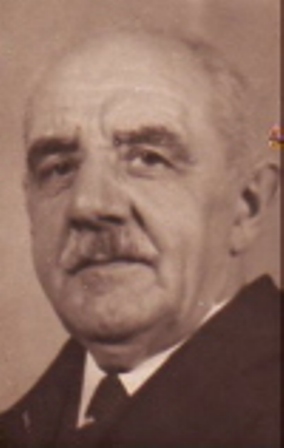

Hermann Hoefer * 1868

Eppendorfer Landstraße 74 (Hamburg-Nord, Eppendorf)

HIER WOHNTE

HERMANN HOEFER

JG. 1868

VERHAFTET 1944

ZUCHTHAUS COSWIG/ANHALT

TOT AN HAFTFOLGEN

13.12.1945

further stumbling stones in Eppendorfer Landstraße 74:

Otto Abendstern

Speech by Hilde Jacobs on the occasion of the unveiling of the Stolperstein for her grandfather on 10 Oct. 2009 at Eppendorfer Landstrasse 74

To begin with, I would like to thank all those who made it possible to lay this Stolperstein for my grandfather, Hermann Hoefer. My special thanks go to the Lions Club for taking on the sponsorship.

Quite some time ago, I learned in the first place that these "stumbling stones” exist at all and that they are laid by the artist Gunter Demnig. I was enthusiastic about the idea, and at some point – unfortunately, only much later – the idea came to me that one could place such a stone for Grandpa Hoefer as well.

Surely, it is no coincidence that in August of this year I walked by here because my daughter Nina works on Eppendorfer Landstrasse. I wanted to visit her and thought, "On that occasion, you might as well look and see whether anything has changed in the vicinity of house no. 74.” I was about to walk on when I looked on the ground – I have no idea why – and discovered, in utter disbelief, this stone. It had been laid only recently, in July 2009, parallel to my intention of seeing to a stumbling stone!

Pleasantly surprised and completely amazed, I racked my brain as to who could have arranged this. Certainly, it had not been a member of my family. There are not too many of us left.

I asked Mr. Diercks about it with whom I was in contact regarding a few documents of the Hoefer family. He referred me to Mr. Hess. From Mr. Hess, I learned that a woman by the name of Hochmuth had organized the investigations into Nazi victims and passed on lists with names to Mr. Hess. One of these lists contained my grandfather’s name.

I have Mr. Hess, Mrs. Hochmuth, and the Lions Club to thank for the fact that all of us have a chance here and now to think of and honor my Grandpa.

What distinguished my grandfather, the Social Democratic teacher Hermann Hoefer, was, as one can read in an obituary by Gerhard Hoch, his voluntary work as a caregiver to the poor. While still a young person, he performed self-sacrificing aid in Hamburg during the time of the cholera epidemic.

He had joined the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1924 and represented that party as a member of the Hamburg City Parliament. He was known for giving even political opponents attention and respect by way of his calm, reflective manner of arguing.

One of his character features was his subtle humor. For instance, once when discussions revolved around the allocation of funds for school equipment, he said, "What is missing in the school on Marienthalerstrasse is a dark room. Even though otherwise we are against ‘dark rooms,’ every school does require a darkroom because photography must be treated in physics class.”

His letters to my mother reveal that he had terrific fun with his two grandchildren, my brothers, as I had not been born back then. When he came to visit, he would walk past the front door on purpose. "Just the other day,” he wrote in a letter about Uwe, who was three or four years old, "I heard him coo at the top of his lungs: ‘Grandpa, you are walking past!’ – So I called out to him, "Well, if you don’t tell me …,’ to which Uwe replied, "But I did shout very loudly!’”

In 1933, my grandfather was, like many other teachers, pushed out of his job, because he did not submit to the Nazi regime without resistance.

He and his oldest daughter, Margarethe, who admired her father very much and was politically active along his lines, were in prison several times.

In July 1943, something incredible happened, with a tragic outcome:

The air raids on Hamburg wreaked such havoc that the public prosecutor’s office felt compelled to grant temporary leave from detention for two months to some 2,000 prisoners awaiting trial. Their number also included Heinz Priess, a friend of Hermann Hoefer. He decided not to report back after the two months had passed, instead going underground. Hermann and Margarethe Hoefer were immediately prepared to hide him in their forest house in Dassendorf.

Both Hoefers were given away by an informer and arrested again.

Heinz Priess was sentenced to death.

When Hermann Hoefer was put on trial in 1944 before the People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof) in Berlin on charges of preparation to high treason (Vorbereitung zum Hochverrat), his wife Nicoline, called Nina, and his son Hermann, were placed under Gestapo detention for several months as well.

Hermann Hoefer was 76 years old when he was transported along with his daughter Margarethe to the penal institution in Coswig.

What I miss in terms of the honors granted to him and Margarethe is commemoration of Hoefer’s youngest daughter Edith, (she is my mother), who after the liberation by the Red Army got them out of the Russian occupational zone, enduring great strains and dreadfulness. My Grandpa, completely weakened and ill, was in a wheelchair and due to a broken arm, Margarethe did not have the strength to take him on the long journey home amidst the post-war chaos. Without hesitation, my mother and a friend of hers set out to get them. The friend was raped by the Russians. My mother was spared this fate because she was already older.

However, all of the strains were in vain, for Hermann Hoefer, having just arrived in Hamburg, died as a consequence of concentration camp imprisonment on 13 Dec. 1945. A seven-year old, I saw him in hospital shortly before his death. I will never forget the sight of the old man, marked by the torture he had endured.

Gretel [Margarethe] Hoefer once wrote to her parents from prison the consoling words, "Everything ends (some day).” In reverence for Hermann Hoefer and his family, I would like to add, "Every end is a new beginning.”

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: October 2016

© Hilde Jacobs

Hermann Hoefer MdHB (Member of the Hamburg City Parliament)

Hermann Martin Hoefer, Member of the Hamburg City Parliament, was born in Hamburg on 21 Aug. 1868. His father was a Catholic shoemaker, who moved to Hamburg from the Rhineland in the 1860s. In Hamburg, he distanced himself from the Catholic doctrine and turned toward Karl Marx’ and Friedrich Engels’ ideas. This shift in basic ideological convictions in his home left a profound mark on Hermann Hoefer’s biography, both professionally and politically.

For instance, in 1877 the father arranged for him to transfer from grade 3 of the Catholic to the public eight-grade elementary school (Volksschule). After finishing his schooling, Hermann Hoefer decided he wished to become a teacher. Completion of the "Präparandenanstalt” (a former designation of the lower, preparatory grades of a teacher training college) from 1884 to 1887 qualified him to attend the three-year teacher training college. In 1890, Hoefer started work as an elementary school teacher within the Hamburg school system. Admitted to civil servant status in 1894, he taught at various Hamburg schools until his retirement, in the very end at the school located at Papendamm 5. On the side, Hoefer temporarily also gave courses at technical and vocational schools in Hamburg.

In addition to school and family – Hoefer’s marriage produced five children – social and political involvement constituted the major substance of his life. Hoefer, who joined the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1892, was primarily concerned with practice-related political work – he never made a name for himself as a theoretician or activist, even in his later years as a member of the Hamburg City Parliament for the German Communist Party (KPD). From his political worldview arose a special interest for social issues, something that manifested itself for the first time in 1892 in his work on one of the voluntary committees for battling the cholera epidemic and afterward in his long-standing efforts for the Hamburg poor relief and welfare authority.

Hoefer advocated his pedagogic ideal in the "Society of Friends of the Patriotic School and Education System” ("Gesellschaft der Freunde des Vaterländischen Schul- und Erziehungswesens”), the reform-oriented teachers’ union at the time. The First World War caused Hoefer to break with the SPD. A member of the "Society for Peace” even before the war, he was a sharp critic of the SPD leadership’s so-called policy of party truce ("Burgfriedenspolitik”). In 1917, when the majority parties, including the SPD, gave up their Reichstag Peace Resolution and bowed to the primacy of the military leadership, Hoefer went over to the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – USPD), which had taken up the cause of battling against continuation of the war. Together with the left wing of the USPD, he joined the KPD in late 1920, a party that had languished more or less on the sidelines until then. Owing to the merger with the Social Democratic Left, however, it became a mass party with about 400,000 members.

In the 1920s, Hoefer initially did not play a prominent role in the Hamburg KPD. Not until Oct. 1928, at the age of 60, did he take a mandate for his party as a successor to a parliamentary seat in the legislature elected only a few months earlier.

The political pragmatist Hoefer criticized the Stalinization of his party carried out in the late 1920s and ranked himself among the so-called "reconcilers” ("Versöhnler”), who strove toward conciliation with the SPD. This may have contributed to him retiring from the Hamburg City Parliament as early as the end of 1930, even before the end of the legislative period. His parliamentary involvement was dedicated to social questions and improvement of the Hamburg school system. In his two years belonging to the parliament, he was a member of the senior school authority and the housing department.

Whether the issue was setting up darkrooms for physics classes or repairing desks – the Communist member of the City Parliament always presented himself as a well-informed and objectively arguing champion of Hamburg schools. To him, the operation of schools had a social function going far beyond the educational mandate: As he explained in his last speech before the city parliament in Sept. 1930, he viewed it as the place where "children living in confined housing conditions can enjoy a modicum of relaxation, joy, and beauty […] at least for five hours a day.”

His public avowal in the same parliamentary speech of the course of action taken by the "Young Spartacus League” ("Jungspartakusbund”), which in its publications published instances of corporal punishment that had become public, naming the circumstances and teachers involved, resulted in a fierce controversy fought out in letters to the editor of the Hamburger Lehrerzeitung. Whereas Hoefer welcomed the educative effect of publications by the "Young Spartacus League” on Hamburg teachers along the lines of "complete elimination of corporal punishment, the Hamburger Lehrerzeitung, pointing to the aims of the Spartacists, accused him of confusing "the classroom with an agitational venue for his own party.”

As for most members of the KPD, the Nazi assumption of power also meant a far-reaching turning point for Hoefer and his family. With reference to the so-called "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” ("Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums”), he was deprived of his pension in 1933. His daughter, also a teacher in Hamburg, was dismissed without notice and retirement pension from school service, his son from the youth welfare office. From then on, the Hoefers, who lived on Eppendorfer Landstrasse at the time, made ends meet by running a small coffee trade facilitated by the former Social Democratic member of the Hamburg City Parliament, Kurt Adams, and by renting out rooms.

However, soon they too became targets of persecution by the Nazi rulers and their authorities. Hoefer himself was interned in the Fuhlsbüttel concentration camp several times in the years 1933 to 1937, his son served a one-year prison term for "illegal work” in 1934/35.

In the Second World War, close contacts developed to the Communist Hamburg resistance. Though Hoefer, by then very advanced in years, did not actively participate in the operations of the Hamburg Communists, he and his family hid two persecutees of the Bästlein resistance organization in his weekend house in Dassendorf in 1943. In 1944, Hoefer and his daughter Margarethe were arrested and charged with "preparation to high treason” ("Vorbereitung zum Hochverrat”). The "People’s Court” ("Volksgerichtshof") sentenced the 76-year-old Hoefer, by then seriously ill with a gastric condition, to one year, his daughter Margarethe to seven years in prison. Hoefer’s wife Nicolina, initially arrested as well, was released after nine weeks in "protective custody” ("Schutzhaft”).

Hermann Hoefer lived to see the end of the war and his hometown for a short time after the hostilities ended. On 23 Apr. 1945, he was freed by Soviet troops from the Coswig (Anhalt) penitentiary. His daughter Margarethe, who had been liberated from the Griebow concentration camp two days earlier, immediately set out with her seriously ill and weakened father on the journey back to Hamburg. Interrupted by several hospital stays, she and her father reached the Hanseatic city in late Nov. 1945. A few weeks after his return home, on 13 Dec. 1945, Hermann Hoefer died in a hospital of the effects of his imprisonment.

Author(s)/copyright: Text courtesy of the City Parliament of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (ed.), taken from: Jörn Lindner/Frank Müller: Mitglieder der Bürgerschaft – Opfer totalitärer Verfolgung, 3rd revised and expanded edition, Hamburg 2012.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg

Stand: October 2016

© Text mit freundlicher Genehmigung der Bürgerschaft der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg (Hrsg.) entnommen aus: Jörn Lindner/Frank Müller: "Mitglieder der Bürgerschaft – Opfer totalitärer Verfolgung", 3., überarbeitete und ergänzte Auflage, Hamburg 2012