Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

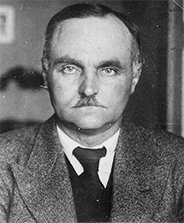

Ludwig Wellhausen * 1884

Kurt-Schumacher-Allee 10 (Gewerkschaftshaus) (Hamburg-Mitte, St. Georg)

HIER ARBEITETE

LUDWIG WELLHAUSEN

JG. 1884

VERHAFTET 1939

’LANDESVERRAT’

ZUCHTHAUS MAGDEBURG

1939 SACHSENHAUSEN

ERMORDET 4.1.1940

further stumbling stones in Kurt-Schumacher-Allee 10 (Gewerkschaftshaus):

Wilhelm Bock

Ludwig Wellhausen

3 Oct. 1884– 4 Jan. 1940

The historian Beatrix Herlemann ("Wir sind geblieben, was immer wir waren, Sozialdemokraten." Das Widerstandsverhalten der SPD im Parteibezirk Magdeburg-Anhalt gegen den Nationalsozialismus, 2001 ["We stayed what we always were, Social Democrats.” The resistance behavior of the SPD in the party district of Magdeburg-Anhalt against National Socialism 1930–1945]) believes that the grouping to which Ludwig Wellhausen belonged was one of the most successful SPD resistance organizations in the German Reich.

Near his native Hannover, in Leinhausen, Ludwig Wellhausen trained as a mechanical engineer in a railroad workshop. He went to sea from 1902 to 1911 as a machinist’s assistant and later as a patented naval machinist on merchant ships. Until 1914, he worked as a master machinist at a power plant in Hamburg. During the First World War, he was employed as a master machinist. In 1919, he found employment in the port of Hamburg as a supervisor at the Norderwerft shipyard, where he was probably a member or chair of the employee representative committee. Ludwig Wellhausen was head of the Hamburg organization of the free trade union "Werkmeisterverband” until presumably 1924.

From 1926 to 1932, he was party secretary of the Hamburg branch of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). Worth mentioning, apart from the extensive everyday activities, is the organization of the large mass demonstrations from 1931 to 1933.

Starting in Jan. 1933 until the ban on June 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen was district secretary of the Magdeburg SPD.

Finally, from 1934 to 1938, he found work at Maschinenfabrik Buckau, R. Wolf, a machine manufacturer, in Magdeburg as a fitter and repair mechanic.

He agreed with the members of the SPD’s Magdeburg-Anhalt district executive, Werner Bruschke, responsible for finances, education, and communal affairs, and Ernst Lehmann, responsible for youth, that the Nazis were a great danger for democracy. They therefore considered it urgently necessary to prepare the party quickly for work underground.

At a meeting in Berlin, one day before the SPD ban on 22 June 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen was elected to the advisory board as well as to a committee of five "principals” ("Vormänner”), a kind of illegal SPD leadership. It was to head the work across the Reich in case of the arrest of the acting executive committee.

In the six years since the Nazis had assumed power until 1939, Ludwig Wellhausen, Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann maintained a wide-ranging information network that stretched

from the Old March (Altmark) to the Vorharz municipality in their former party district of Magdeburg-Anhalt, including about 50 towns and villages such as Stendal, Burg, Dessau, Köthen, Stassfurt, Halberstadt, Aschersleben, Wernigerode, and Thale. Above all, programmatic discussion was important to them. Most of the SPD members had a great need for information, which they could not satisfy, of course, from the regular press, "forcibly coordinated” ("gleichgeschaltet”) by the Nazis.

On 12 Jan. 1939, Ludwig Wellhausen was arrested together with 19 other party comrades from Magdeburg and the surrounding area in the prelude to a massive wave of arrests that mainly affected Social Democrats, and he immediately experienced severe mistreatment.

Until 9 Aug. 1939, he was a prisoner in Magdeburg’s police prison, although the investigating judge had enjoined the issuing of an arrest warrant as early as Apr. 1939. On that day, he was taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp without trial on "suspicion of high treason.” Ludwig Wellhausen died on 4 Jan. 1940.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: December 2020

© Enkelin Beate Blanke, geb. Wellhausen

Ludwig Wellhausen, born 3.10.1884 in Hanover, arrested 12.1.1939, Magdeburg penitentiary, murdered 4.1.1940 in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Olendörp 33 and Kurt-Schumacher-Allee 10 (Trade Union House)

My grandfather is alive. Since I have been researching his biography, even more so. But even when I was a child, many stories were told in the family in which he appeared as a loving, humorous and careful father and husband.

Since I know about his mistreatment in the prison in Magdeburg in 1939 and his imprisonment in the concentration camp Sachsenhausen in 1939/40, since I got to know how important and far-reaching his resistance activities as a Social Democrat from 1933 to 1939 were in the Magdeburg area, which party functions he held in Hamburg from 1926 to 1932, it seems to me as if the stories of grandmother and mother were one-sided They did not talk about his resistance activities and also not about his imprisonments in prison and concentration camps. When I discovered a dusty box in the cellar containing numerous letters and documents, especially from the years 1939/40, it was clearer that they must have suffered greatly from the trauma. Only activities of the History Workshop Willi Bredel Society moved my mother to speak publicly about it. I think that my grandmother, my mother and her siblings had to struggle hard because the survival of the family during his imprisonment and after his murder and the long years of tenacious struggle for reparations (until 1966) kept his life story very much alive. Unspoken, he was a hero. I therefore set out to learn more. The sources are quite good, although many documents have disappeared or were burned in the storming of the Magdeburg police building on June 17, 1953.

A memorial stone in Magdeburg's Westfriedhof and his gravestone on our family grave in Ohlsdorf, two brief mentions in the Gedenkbuch der deutschen Sozialdemokratie im 20. Jahrhundert (2000) and in the book "Gewerkschafter in den Konzentrationslagern Oranienburg und Sachsenhausen" (Trade Unionists in the Concentration Camps of Oranienburg and Sachsenhausen) provide little information about his work and aftermath. Fortunately, historian Beatrix Herlemann has compiled a wealth of information in her 2001 book on the resistance of the Magdeburg Social Democrats to National Socialism. According to her, the grouping to which my grandfather belonged was one of the most successful SPD resistance organizations in the German Reich. I was able to base my research on her work and her additional references, so I found some more information.

Near his birthplace of Hanover, in Leinhausen, Ludwig Wellhausen learned as a machinist in a railroad workshop. He went to sea from 1902 to 1911 as an assistant machinist and later as a patented sea machinist on merchant ships. Until 1914, he worked as a machine master in an electric power plant in Hamburg. From 1915 until after 1918, he repaired submarines for the Reichswehr in Kiel, Constantinople and later Sevastopol. In 1919 he found employment in the Port of Hamburg as a foreman at the Norderwerft shipyard. From 1924 he worked for the Stolzenberg company, notorious for poison gas accidents, on whose behalf he spent five months in the Soviet Union supervising the construction of a chemical factory (probably for gas or also gas containers) until it was commissioned. In the meantime he was probably a member or chairman of the works council of the Norderwerft.

Ludwig Wellhausen was head of the Hamburg organization of the free trade union "Werkmeisterverband" until probably 1924. I have found a picture of the 1930 meeting in Hamburg, in addition to some excursion photos showing colleagues from Bremen.

From 1926 to 1932 he was party secretary (today: managing director) of the Hamburg SPD. Worth mentioning, in addition to the extensive day-to-day activities, is the organization of the large mass demonstrations from 1931 to 1933. From January 1933 and until the ban in June 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen was district secretary of the Magdeburg SPD.

Finally, from 1934 to 1938 he found work at the Buckau machine factory, R. Wolf, in Magdeburg as an assembler and repair fitter. On the occasion of trips for mounting work to Turkey and Finland in 1937, friends advised him to stay there. However, emigration was obviously out of the question for him. Presumably he did not want to abandon his family and the comrades of the resistance group.

He agreed with the members of the SPD district leadership in Magdeburg-Anhalt, Werner Bruschke, responsible for finance, education and municipal affairs, and Ernst Lehmann, responsible for youth, that the National Socialists represented a great danger to democracy. A speedy preparation of the party for underground work therefore seemed to them urgently necessary. Werner Bruschke had initiated this by introducing two types of accounting, according to which party members could no longer officially be traced through postal and monetary transactions.

At a meeting in Berlin, one day before the SPD ban on June 22, 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen was elected to the executive committee as well as to a body of five "Vormännern," a kind of illegal SPD leadership. They were to lead the work in the Reich in the event of the arrest of the incumbent executive committee. In official and then informal meetings, the participants in the board meeting had not been able to agree on an assessment of the situation; some took the view that an albeit limited existence of the SPD was probable, while others advocated well-organized underground activity in order, according to Ludwig Wellhausen, to keep Social Democratic ideas and plans in the minds of the comrades. Werner Bruschke reported that they had represented each other; he had gone to some of these meetings in February and the second half of 1933. Evidence shows that on June 9, 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen was with the group of the part of the SPD presidium that had been exiled to Prague, which included Erich Ollenhauer.

Ludwig Wellhausen, Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann, all three of whom had already been high-ranking regional functionaries of the SPD for years and decades, were of the opinion that in order to maintain a network of Social Democratic contacts, even under illegal and dangerous conditions, regular contact and exchange of information was necessary. This was to be accomplished through conversations as well as through illegal newspapers and leaflets. Although they were very careful not to maintain risky links with former comrades who were fickle, fearful, or even Nazi, they nevertheless tried to include as many old groupings as possible in their network and to supply them with written material.

In the first six years after the National Socialists took power, until 1939, Ludwig Wellhausen, Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann maintained a wide-ranging information network that stretched from the Altmark to the foothills of the Harz Mountains in their former party district of Magdeburg-Anhalt and covered some fifty places, including Aschersleben, Burg, Dessau, Halberstadt, Köthen, Staßfurt, Stendal, Thale and Wernigerode. Above all, programmatic discussion was important to them.

Most SPD members had a great need for information, which they could not, of course, satisfy from the same-society press.

At first, the SPD newspaper "Neuer Vorwärts" (New Forward), which had a total circulation of 14,000 and was produced by the SPD exile executive in Prague from June 1933 onward and secretly shipped in suitcases, was distributed and used as a basis for discussion. The journey to Prague or to Tetschen-Bodenbach in Czechoslovakia was arduous, as it was necessary to cross the border illegally. Initially, they also used this surreptitious route to organize the suitcases containing the exile edition of "Neuer Vorwärts," which were sent by express to Magdeburg to deck addresses. However, there was a great deal of criticism of this procedure: Werner Bruschke considered the newspaper, with its current daily political news, unusable because of the late delivery; moreover, the dispatch by rail or mail was dangerous, because anxious deck address recipients, including even SPD members, had reported the matter to the police.

They completely broke off contact with the Prague-based party executive, the "Sopade" (as the SPD's foreign executive was called), starting in January 1934. During their repeated arrests and interrogations, Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann had suspected that a Gestapo informer in Tetschen-Bodenbach, presumably even as a fellow member of the SPD office there, had betrayed their distribution of the "Neuer Vorwärts". However, they had been targeted by the Gestapo through the arrest of the leadership of the Socialist Workers' Youth (SAJ) in Berlin, which had named their contacts in Magdeburg and other places in cruel torture interrogations. My grandfather and his comrades were helped, however, by the fact that some of the Magdeburg police officers had formerly been members of the SPD. Thus, one interrogator left the interrogation room at one point, so that Werner Bruschke could take a look at the open file and they could then talk among themselves. From then on, the group produced its own leaflets and distributed the press review "Blick in die Zeit".

"Blick in die Zeit" was an unusual magazine. Domestic and foreign newspaper reports tolerated by the Ministry of Propaganda, as well as quotations from literature, were published side by side with little commentary. The nature of the clippings, however, and their compilation gave politically interested people who could read between the lines a very good insight into actual world events. The press review was produced in Berlin and had a very wide circulation throughout Germany, with a print run of 100,000 copies (and an estimated 500,000 readers through circulation in reading and discussion circles). It served as a counter-publication to Nazi newspapers. The Social Democratic print shop owner Kurt Hermann Mendel and Dr. Alfred Ristow, a former Prussian police officer who had already published two smaller magazines, did not need official approval for the newspaper because they already owned a commercial enterprise. The editor was the former editor of the "Schleswig-Holsteinische Volkszeitung," Andreas Gayk. Distribution was organized through the network of the Reichsarbeitsgemeinschaft der Kinderfreunde, through its secretary Hans Weinberger, and by means of a former ADGB (General Federation of German Trade Unions) employee through contacts with former Social Democratic and trade union bookstores.

In the first months, all available, often derisive, reports on the whereabouts of persecuted party comrades* were printed. Later, forms of resistance and escape routes, smuggled camouflage writings, and still ongoing trips of Marxist youth groups were mentioned in this special way. But also foreign ostracisms of the "new Germany" or quite unsuccessful outpourings of their own representatives as well as corruption cases of Nazi protagonists were cited in the magazine. Accordingly, the discussions were particularly fruitful on the basis of this journal. Moreover, the distributors did not run the risk of being prosecuted, since the press review was legal until August 1935. For example, Karl Grimm, who belonged to the resistance group, had to be released in Oebisfelde after six hours of interrogation because only "Blick in die Zeit" sheets could be found on him.

Ludwig Wellhausen distributed "Blick in die Zeit" together with Werner Bruschke through his washing machine agency. Ludwig Wellhausen had founded it after Werner Bruschke's tobacco store at the Neustädter Bahnhof in Magdeburg, with a strategically unobstructed view in all directions, had proved too unsafe. The newspaper was an important means of communication for further cohesion. Many distributors combined illegal work with feeding the family. They often "camouflaged" their walks by selling food, often the only way to earn money due to the forced unemployment caused by previous union or SPD activities.

Two episodes may illustrate the underground work: For a long time, Werner Bruschke had two take-off machines for leaflets in the pub of a comrade friend in Sudenburg, whose wife, however, rejected this "print shop." A former tennis partner then helped. In her father's car repair shop in Puppendorf on Berliner Chaussee, Bruschke placed the machines, which were never found by the Gestapo.

The daughter of the former "Volksstimme" editor Albert Pauli, Hertha Pauli, told me the further episode. At the beginning of the illegal activity, in early to mid 1933, Ludwig Wellhausen, Werner Bruschke, Albert Pauli and the former editor of the "Volksstimme", Alfred Meisterfeld, met in the cafe "CK" to plan their activity. The children, including Hertha Pauli and her sister, my mother Lieselotte and her brother Hans, all between six and eleven years old at the time, were there and played together. Then, when Albert Pauli and his wife Ilse were arrested and tortured for about four weeks in 1933, they met conspiratorially, often in a settlement cottage at Franz Lange's home in western Stadtfeld. During the Weimar Republic, Lange was the managing director of the Construction Workers' Association and the housing administrator of the Magdeburg Building Lodge. He had important contacts with the Leuschner Group, which planned the establishment of trade unions after the liberation, and thus with the domestic and foreign resistance.

In addition, Ludwig Wellhausen, Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann used the SPD treasury in Magdeburg, which had been saved from the Nazis and contained about 40,000 Reichsmarks, to provide for family members in need as a result of persecution and arrest. Whether other friends and acquaintances also benefited can only be assumed. However, Ludwig Wellhausen demonstrably helped the Jewish physician Dr. Walter Landau from Magdeburg and his family, with whose son Vincent I am in correspondence.

Walter Landau was the senior physician at the municipal tuberculosis care center. He was advised to leave the country in 1938. He emigrated by ship of the Hamburg-America Line via Southhampton to New York, where he arrived on October 15, 1938. Later, he went to Baltimore, where, after great initial difficulties, he found a job as a doctor. His wife Anni and their eight-year-old son Vincent were urged by my grandmother to flee as well, without stopping in Magdeburg, because of their unswerving loyalty to their Jewish husband and their classification of their son as "half-Jewish." With the help of family members in Berlin and Belgrade, they left Europe six months later via Le Havre for New York. It is very likely that my grandfather organized the passage by ship, based on Walter Landau's letter of early October 1938, which was intended to disinform the Gestapo. In view of the consequences of the decision to leave Germany, the letter seems trivial on the one hand and indefinite on the other. However, one can gather from the letter that Walter Landau was very unhappy and worried. Vincent Landau did not know anything specific about this action because, according to his own words, his parents wanted to keep the horrors of persecution and humiliation away from him. It was bad enough that many relatives and friends of Walter Landau had been deported and killed in extermination camps. Vincent Landau remembers, however, that the name "Wellhausen" had always been associated with warmth and friendship in his family.

This departure was camouflaged by an unusually detailed series of photographs in one of my grandmother's albums. From September 25, 1938, she accompanied my grandfather for a few days in Upper Silesia, where he worked on assembly at least from September 7, 1938, until beyond November 7, 1938. There are numerous dated receipts of mountain hikes, lunch breaks, and city visits, often together with a married couple who were friends. In addition, I possess a letter that he wrote to my mother from Weizenrodau, Upper Silesia, during this time. The suspicion that he might have gone to Hamburg in between should certainly not arise.

Every now and then I leaf through the photo albums that my grandmother had created. I can't shake the feeling that she was very careful in her selection and documentation: By this I mean that, except for the trip mentioned above, she rarely added dates and names to the photos. If you carefully detach individual photos that are very tightly glued, you will find innocuous names and dates such as birthdays or weddings of family members. There are many faces that are unattributable. The old albums are "jumbled," meaning time sequences are not followed.

Endangered persons do not appear at all in the series 1933 to 1945, such as Werner Bruschke, Ernst Lehmann and others, except for one photo of a happy celebration, without datie undated (probably New Year's Eve 1934). It shows from left to right Trudi (Gertrud) Bruschke, Werner Bruschke, Ludwig Wellhausen, Margarethe Wellhausen, Lenchen (Helene) Meisterfeld, Alfred Meisterfeld and probably the sister of Werner Bruschke, Elisabeth Bruschke. It is highly likely that it was taken in one of the living rooms of the "Reform" estate in Magdeburg, where the Bruschkes and Wellhausens lived. However, the Wellhausen-Bruschke-Lehmannn resistance group had to avoid contact with well-known public figures in order not to jeopardize the newly established networks. This was apparently particularly difficult in the case of Ernst Reuter, Magdeburg's mayor and a friend of the family. Since he unswervingly sought open contact with the citizens, he was a particular thorn in the Gestapo's side. Until 1934 he was arrested three times and then emigrated to Ankara via the Netherlands and London after long persuasion by his political friends. There are no pictures of him and his wife Hanna in Grandmother's albums.

A photo from Margarethe Wellhausen's albums, however, clearly shows, among other unidentifiable men, the metal worker, trade union official, and deputy community leader in Groß-Ottersleben, Paul Graf. The men had taken a trip with the Wellhausen family to the Bode River in the Harz Mountains in May 1933. I assume that they used this opportunity to make political arrangements.

Until 1939 Ludwig Wellhausen, obviously not known to the Gestapo until then, was effective in many ways, until he was arrested on January 12, 1939, in the run-up to a wave of arrests that mainly affected Social Democrats, together with another 19 comrades* from Magdeburg and the surrounding area, and was immediately severely maltreated. My mother Lieselotte Wellhausen, then 14 years old, happened to see him with a bloody beaten head on the way to school, when he had to walk the 2-3 km from the prison to the hospital under guard because of middle ear infection with facial paralysis and fever. He did not recognize her, whether it was out of caution or drowsiness is not clear. According to reports of the former head of the feature pages and deputy editor-in-chief of the "Magdeburger Volksstimme" Emil R. Müller via detours to Erich Ollenhauer in Paris, who in turn had already been informed by the former Magdeburg editor of the "Reichsbanner" newspaper Franz Osteroth, who had established and maintained manifold international contacts through journalistic work in Copenhagen, Ludwig Wellhausen was "so battered that he had to be transferred to the hospital, where his wife could hardly recognize him." According to the prison book of the Magdeburg city archives, his admission to the Sudenburg hospital took place on February 20, 1939. From February 21 to March 30, 1939, he was in the prison hospital. Two operations were performed for otitis media and cartilage suppuration with hemifacial paralysis. According to my mother's recollections, she visited him in the hospital during this time. In letters that exchanged between my grandmother and my grandfather, there are the following passages that were apparently not censored: "[...] one envies the people who quit in time. They have everything behind them.[...] I can sleep even worse now than usual" (Jan. 29, 1939, L. W.); "I thought you slept badly at night" (Feb. 3, 1939, M. W.). ); "The constant brooding, especially during sleepless nights, is terrible" (Feb. 5, 1939, L. W.); "You never had anything wrong with your ears" (Feb. 26, 1939, M. W.); "[...] that the lump on your cheek is caused by a tooth ulcer (?). A few teeth are loose and might have to be pulled, although they are healthy. [...] It has nothing to do with the ear, [...] if the two ailments are not signs of another internal disorder in general" (4.5.1939, L. W.).

Until August 9, 1939, Ludwig Wellhausen was imprisoned in the Magdeburg police prison, although the issuance of an arrest warrant had already been prohibited by the examining magistrate in April 1939. On August 9, 1939, he was taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp without trial on "suspicion of high treason." From the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Ludwig Wellhausen's letters contain only very hidden references to his physical and mental condition: "In health I cannot complain" (probably August 1939) as well as "you will [...] have and keep me so in the same memory" (probably September 1939). That winter there were often very high sub-zero temperatures. This led to a high mortality rate among the debilitated concentration camp prisoners.

My grandmother, who received unclear and contradictory information about the burial place of her husband, also had to experience how relatives were treated. Despite repeated inquiries, she was only briefly informed about the alleged course of the illness and the cause of death ("asthma") on March 1, 1940. Ludwig Wellhausen had already died on January 4, 1940.

Werner Bruschke and Ernst Lehmann had been arrested together with Ludwig Wellhausen. Werner Bruschke experienced the liberation in the Dachau concentration camp in poor health. After 1945 he was, among other things, Minister of Finance of the Provincial or State Government of Saxony-Anhalt and from 1949 to 1952 Minister President of the State of Saxony-Anhalt.

Ernst Lehmann was among the approximately 7,000 victims in the bombing of prisoner ships by the Royal Air Force on May 3, 1945, in Neustadt Bay.

Translation Beate Meyer

Stand: March 2023

© Beate Blanke, geb. Wellhausen

Quellen: Landeshauptarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Magdeburg, Rep. C 29 Pol Präs Ug bug III, Gefangenenbücher, Buch 6, 1939; Briefe und Papiere in Privatbesitz: Fotos, Postkarten (25.9.1938–28.10.1938 bzw. 7.11.1938) und ein Brief von Ludwig Wellhausen an Lieselotte Wellhausen aus Weizenrodau, 7.9.1938 – Briefe von Ludwig Wellhausen an Margarethe Wellhausen aus dem Polizeigefängnis Magdeburg, 29.1., 5.2., 2.4. u. 4.5.1939 – Brief von Ludwig Wellhausen an Margarethe Wellhausen aus dem Gefängnislazarett Magdeburg, 26.2.1939 – Briefe von Margarethe Wellhausen an Ludwig Wellhausen ins Polizeigefängnis Magdeburg, 3.2. u. 26.2.1939 – Gesuch von Margarethe Wellhausen an Ministerpräsident Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring vom 13.6.1939 zur Aufhebung der Schutzhaft von Ludwig Wellhausen, Durchschlag – Briefe von Ludwig Wellhausen an Margarethe Wellhausen aus dem KZ Sachsenhausen, wahrscheinlich August und September 1939 – Briefe von Margarethe Wellhausen an die KZ-Kommandantur Sachsenhausen bzw. den leitenden Arzt der Krankenabteilung, 7.2. bzw. 29.3.1940, Durchschläge – Brief der KZ-Kommandantur Sachsenhausen an Margarethe Wellhausen, 1.3.1940 – Briefe und Postkarten von Dr. Walter Landau und Anni Landau an Ludwig Wellhausen bzw. Margarethe Wellhausen, Anfang Oktober 1938 und Anfang März 1939 bzw. 13.6.1946 – Erinnerung Margarethe Wellhausen: Briefe von Dr. Walter Landau (Anfang Oktober 1938 und 13.6.1946) und Vincent Landau (März bis September 2006) an Beate Wellhausen – Gesuch von Margarethe Wellhausen an Ministerpräsident Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring vom 13.6.1939 zur Aufhebung der Schutzhaft von Ludwig Wellhausen, Durchschlag – Lebensläufe, 1911 handschriftlich von Ludwig Wellhausen, ca. 1934 getippt, ca. 1960 komplettiert und neu getippt von Margarethe Wellhausen; Erinnerungen Margarethe und Lieselotte Wellhausen, Aufstellung seiner Daten durch Margarethe Wellhausen nach 1945 und ca. 1960, unveröffentlicht, S. 108–110, 112 f., 123–129, 133, 200 f., 218; Ulrich Bauche u. a.: Arbeiterbewegung in Hamburg von den Anfängen bis 1945. Katalogbuch zur Ausstellung des Museums für Hamburgische Geschichte, Hamburg 1988; Werner Bruschke: Episoden meiner politischen Lehrjahre, hrsg. von der Kommission zur Erforschung der Geschichte der örtlichen Arbeiterbewegung bei der Bezirksleitung der SED, Halle 1979, S. 53, S. 58 f., 63 f.; Magdeburger Stadtjournal, 24.2.1995, S. 3; Beatrix Herlemann: "Wir sind geblieben, was immer wir waren, Sozialdemokraten". Das Widerstandsverhalten der SPD im Parteibezirk Magdeburg-Anhalt gegen den Nationalsozialismus, Halle 2001, S. 14, 70, 75, 87 f., 91, 98, 101 f., 104 f., 106, 221 f.; Vorstand der deutschen Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands (Hrsg.): Der Freiheit verpflichtet. Gedenkbuch der deutschen Sozialdemokratie im 20. Jahrhundert, Marburg 2000, S. 219 (Erinnerung Lieselotte Wellhausen), 220 f. (Brief von Karl Raloff im August 1939 aus Kopenhagen an Erich Ollenhauer in Paris, nach Informationen seines Schwiegervaters Emil R. Müller, der mit der Familie Wellhausen befreundet war); Jürgen Jensen/Karl Rickers: Andreas Gayk und seine Zeit 1893–1954. Erinnerungen an den Kieler Oberbürgermeister, Neumünster 1974; Harry Naujoks: Mein Leben im KZ Sachsenhausen, 1936–1942. Erinnerungen des ehemaligen Lagerältesten, Köln 1987, S. 144–147, 159 f., 293; Carmen Stange: Wellhausen, Ludwig (1884–1940). Deutscher Werkmeisterverband, in: Mielke Siegfried (Hrsg.): Gewerkschafter in dem Konzentrationslagern Sachsenhausen und Oranienburg. Biographisches Handbuch, Bd. 1, Berlin 2002, S. 297 f.; Schiffslisten der Auswanderungen 1933 bis 1945, Ballin Stadt-Museum, Hamburg-Veddel, https://www.ballinstadt.de/informationen/familienforschung/, eingesehen am: 5.4.2022; Telefonat mit Hertha Pauli am 16.9.2007.