Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Walter Herz * 1899

Rothenbaumchaussee 101/103 (Eimsbüttel, Rotherbaum)

HIER WOHNTE

WALTER HERZ

JG. 1899

EINGEWIESEN 1940

HEILANSTALT LANGENHORN

"VERLEGT" 23.9.1940

LANDES-PFLEGEANSTALT

BRANDENBURG

ERMORDET 23.9.1940

AKTION T4

further stumbling stones in Rothenbaumchaussee 101/103:

Bertha (Berta) Herz

Berta Herz, born on 26 Oct. 1900 in Hamburg, deported on 23 Sept. 1940 to the euthanasia killing center in Brandenburg

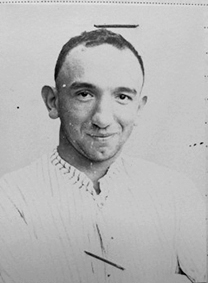

Walter Herz, born on 19 May 1899 in Hamburg, deported on 23 Sept. 1940 to the euthanasia killing center in Brandenburg

Rothenbaumchaussee 101–103

On 8 Dec. 1925, the steward Walter Herz showed up at the police station at Dammtorstrasse 10 in Hamburg-Neustadt and asked expressly to have Prof. Dr. Max Nonne observe him concerning his mental state with a view to "whether he would be able to study astronomy at the observatory.” Another reason, Herz said, was that his relatives wished to have him committed "to the lunatic asylum” ("Irrenanstalt”). He agreed to have himself admitted to the Harbor Hospital, and the mother, where he was registered as residing, was notified. Walter Herz trusted the renowned neurologist Max Nonne because of earlier examinations.

Walter Herz was born on 19 May 1899 into a rising merchant family. The family and business history began in 1895 with the founding of a watch and gold articles storehouse at Amelungstrasse 13/14 in Hamburg-Neustadt by his uncle, Neumann Nathan. Neumann Nathan was born in Hamburg as the son of a tailor on 11 Nov. 1871. The income of his father, Gerson Nathan from Rendsburg, met the requirements to be naturalized along with his family as Hamburg citizens in 1887. The family included his wife Recha, née Joseph, the oldest daughter Helene, born on 1 Dec. 1870, the one year younger brother Neumann, and two additional brothers, Julius, born on 25 Sept. 1873, and Marcus, born on 14 Feb. 1877.

As the first of the Nathan siblings, on 24 Jan. 1895 Helene married the upholsterer and decorator Henry Herz of the same age, born on 13 July 1870 in Hamburg. His father, Sander Levy Herz, ran a decoration and furniture store at Hermannstrasse 27 in Hamburg-Altstadt; the family, comprised of the mother Selde, née Wolffsohn, and the sisters Auguste, Jenni, Sophie, and Franziska, lived in Harvestehude at Eichenallee 3.

Until getting married, Helene Herz had lived in Hamburg-Neustadt. The young couple relocated to the Grindel quarter, initially moving into an apartment at 2nd Durchschnitt 10, where before the year’s end, on 17 Nov. 1895, their first child, Herta, was born. Two years later, when they had moved into a more upscale apartment at Durchschnitt 11, their second child, Manfred, was born on 25 Nov. 1897. He was followed by Walter on 19 May 1899 and eventually, on 26 Oct. 1900, Berta.

Two years after his sister, Neumann Nathan married the daughter of a typesetter, Helene (Lenchen) Gumpel. On 13 Oct. 1898, she gave birth to their first child, son Max, who only reached the age of nine months, however. On 11 July 1900, their second child, Lilly, was born, three months before her cousin Berta. Lilly remained the only child, and this meant that Neumann Nathan did not have a natural male successor for his business.

The grandparents, Recha and Gerson Nathan, passed away in 1903 and 1910, respectively, so that they were not able to experience their grandchildren’s further development. Herta, Manfred, and Berta Herz successfully completed their schooling. Manfred Herz (see corresponding entry) received training for the skilled trade of a cabinetmaker; Herta and Berta became office employees. In contrast to that, Walter’s years of schooling and training were full of changes. He attended the Talmud Tora Realschule at Kohlhöfen 19, went along during its relocation to the new building at Grindelhof 30, but then left the school after seven grades. He completed his years of compulsory school attendance at Albert Silberberg’s "Israelitic Educational Institution” ("Israelitische Erziehungsanstalt”) in Ahlem near Hannover. Afterward, he began a commercial apprenticeship, which he quit after three months though. After several jobs as a messenger, he tried his hand in training as a shoemaker, which he did not finish either. On 8 Oct. 1917, he was drafted into the army but discharged again after three months. Following a short period of working as a messenger with Blohm & Voss, he went to sea as a steward, changed ships and the position, and returned as a stoker to Hamburg in 1923. By then, the marriage of his uncle Neumann Nathan had ended in divorce, and so had his parents’ marriage in 1922. As early as 1919, his mother, Helene Herz, had taken over management of a summer guesthouse in Niendorf on the Baltic Sea, passing the position to his brother-in-law, whom he did not know yet. In Mar. 1921, Herta, the oldest sister, had married the merchant Hans Fabian, born on 10 June 1893 in Berlin. Even in those days, Hans Fabian already suffered from occasional epileptic seizures that subsequently worsened. Henry Herz, Walter’s father, married a second time and apparently no longer played any significant role for his son, as did the entire family on his father’s side.

Neumann Nathan took his nephew Manfred Herz into his company, for a time Walter as well. After a short while, Walter left the business again, and Manfred managed the enterprise through the period of inflation.

Walter Herz went to sea again. The journey took him to California, where he fell ill. It is not possible to reconstruct exactly the chronology of his activities and hospital stays, as well as the diplomatic assistance he enlisted. In San Francisco, he was first "locked up in a lunatic asylum,” as he later put it, then transferred to a hospital, from which he was discharged sufficiently healthy to embark on the homeward journey. In Oct. 1924, he arrived in Bremen and immediately travelled onward to Berlin to report to a senior civil servant (Regierungsrat) by the name of Davidsen in the Foreign Ministry on "certain incidents” on the passage and to apply for admission to the Berlin University Hospital "due to shattered nerves.” Nevertheless, right away he journeyed to South America, where he struggled to make ends meet as a kitchen boy and dishwasher, but also as a reporter, ending again with an admission to hospital. During the return trip on the steamship Antonio Delfino in Feb. 1925, he documented the events on both journeys in a letter. This consisted of "strange astronomical observations:” "Since during the homeward journey on the steamer, from Buenos Aires all the way past Rio des [sic!] Janeiro, I was drawn to such an extent by an invisible force at night, I had to go to the upper deck and lie down under the stars. As long as the tropical sun was not shining, I was completely in the power of the heavenly bodies, and to this day I am still under the influence of the sun, the moon, and the stars.” According to him, this constituted the main reason why he had reported to the police station. Moreover, he said, the black beard of the "Jewish cook” Mendel, his neighbor on the steerage, had suddenly been gray one morning. Mendel, he went on, had told him that he had made such grave prophecies that his beard had turned gray with fright. He, Walter Herz, had asked the captain whether he should be observed by an astronomer, so that, "in case I am in a position to interpret stars, it [is] my greatest wish to put myself at the government’s disposal.” He added that he had also documented his observations photographically and named diplomatic personnel as witnesses. The reports contain associations to the Jewish tales of the dream reader Joseph and his rise to head administrator in Egypt.

In Dec. 1925, Walter Herz stayed in the Harbor Hospital for three days. From there, he was transferred to the Friedrichsberg State Hospital (Staatskrankenanstalt Friedrichsberg) with a diagnosis of "manic state of excitement of a schizophrenic patient.” In the strange surroundings, all sorts of things seemed suspicious to Walter Herz in the beginning. Nevertheless, to the admitting physician, he appeared to be pleased, talking incessantly, "sometimes angrily, sometimes cheerfully.” The doctor attested to him conceitedness and illusions, changing the diagnosis to imbecility and Propfhebephrenie, i.e., medium-level feeble-mindedness on which was superimposed ("aufgepropft”) schizophrenia. The physical yielded no pathological findings, except that the second toe was missing on the left foot; it had been amputated in 1917. Walter Herz was 1.73 m (about 5 ft 8 in) tall and weighed 55.5 kg (111 lbs), so he was a thin man. By the time he was discharged five months later, he had gained 15 pounds.

According to information by her brother Walter, Berta Herz had had mild epileptic seizures for the first time at age 17. Until 1925, she worked as a commercial clerk, then becoming unfit for gainful employment and receiving a monthly pension of 39 RM (reichsmark). She lived at Schlüterweg 3, which was later renamed Rothenbaumchaussee 101/103, the address where Walter was registered with the authorities as well. Berta had already been admitted once before her bother to the Friedrichsberg State Hospital, but was discharged again to go home. Walter Herz was discharged as well but to the Langenhorn "sanatorium and nursing home” ("Heil- und Pflegeanstalt” Langenhorn). When admitted in Apr. 1926, he made a positive impression on the physician due to his liveliness, when he gave a detailed and self-critical account of his life to date. The doctor summed up his conclusion from this as follows: "[The] patient has the mental agility characteristic of his race and splutters out everything at untiring speed; apparently, he is very sure of his own importance and regards his presence here as temporary and merely as aimed at ‘establishing his mental state.’”

Berta and Walter were financially supported by Manfred Herz, to whom Neumann Nathan had left his company by then and who had successfully consolidated the business.

After the divorce of her parents Neumann and Lenchen, Lilly Nathan (see corresponding entry) had stayed with her mother. She was never able to live independently. She increasingly acted in aggressive ways toward her mother, which is why in 1926, she was committed to a psychiatric private hospital in Uelsby. Apparently, enough family funds were available to cover the costs, in contrast to Walter Herz, whose accommodation was paid for by the Hamburg social administration. After his admission in "Langenhorn,” he was employed in the bookbindery. Vis-à-vis his fellow patients, he increasingly behaved provocatively, which resulted in friction. In order to avoid further problems, he ate his meals alone in the "observation room” [Wachsaal – a room in which patients were immobilized and underwent continuous therapy]. One incident on 3 May 1926 changed his attitude toward staff fundamentally: His mother had requested leave for him in the city, which he was denied on grounds offensive to him. Thereupon, he refused to work for the time being. When he resumed his work, he became so abusive toward the assistant medical director (Oberarzt) that he was sent into solitary confinement in the "observation room.” Similar incidents recurred, and Walter Herz spent a lot of time in the observation room or tied to his bed.

He enjoyed writing many letters, of which the institutional administration withheld quite a few. In one letter to his mother, he expressed the hope that he would be "cured quite soon of the feeble-mindedness weighing down on me.” "God willing.” In 1927, he turned to the public health department, requesting that a doctor be sent to examine his intelligence. Though that did not happen, intelligence tests at the institution itself revealed that it was not possible to categorize him as feeble-minded definitively. For a while, hypnosis played a great role for him, both as a hypnotizer and a hypnotized person. Clarification as to whether he was suitable as an astronomer or astrologer preoccupied him from time to time but eventually remained undecided. For some years, the question of his sexual identity weighed heavily on his mind. His abusive treatment of other patients was penalized by the methods common at the time, i.e., continuous baths and stays in the "observation room,” but he was also listened to when expressing his fantasies and wishes, e.g., why he would like to be an eight-year-old girl. "I then would first have to go through the education of a young girl, after all.” After one such conversation, Walter Herz became calmer and did not express any more delusions for the time being. Other times, he stressed that he was a Jew, made little jokes about it, and drew Stars of David on letter margins.

The mother, sister Berta, his aunt Ida, and Lissi (Elise), the wife and daughter of his uncle Julius Nathan, visited him; uncle Marcus Nathan supplied him with what he needed from his men’s clothing store. At the same time, Marcus Nathan was his property administrator. When Walter required orthopedic shoes, he would receive them from his family, who also brought money for the daily paper and at his free disposal. He needed little because he neither smoked nor enjoyed sweets.

He frequently changed activities; for instance, transporting sand with a wheelbarrow did not meet his standards and was too physically straining for him, but the weaving shop satisfied him for the time being.

By that time, Helene Herz had devoted herself to the Christian Science Church, deciding in 1927 to leave the Jewish Community. When the mental-emotional illnesses of her children Walter and Berta as well as her son-in-law Hans Fabian worsened, Helene Herz found support with the "practitioners” of Christian Science, men and women who healed according to the teachings of Mary Baker Eddy. She was also hurting from the deaths of her brothers Neumann and Julius in 1932 and 1933; added to this was the general threat setting in with the transfer of political power to Hitler.

The chronology of the events that followed is contradictory. On 7 Oct. 1936, Berta Herz was once again admitted to the Friedrichsberg State Hospital; according to another source, she was already committed to the Langenhorn "sanatorium and nursing home” on 3 Nov. 1935. No details are known about her medical condition.

In order to relieve the Langenhorn institution, Walter Herz was transferred to Strecknitz "sanatorium” near Lübeck on 21 Sept. 1938. As a physically and neurologically healthy patient, he was able to work in the farming operation. Again, his intelligence was tested, and again, no feeble-mindedness could be established, but "a high degree of impaired judgment because of distraction and megalomaniac ideas.” Time and again, he presented to doctors and caregivers his wishes in a polite manner, though he appeared very obtrusive in doing so, which branded him as a "querulous person.” There were frequent conflicts with his fellow patients, and these incidents were penalized with him being put in solitary confinement.

In 1938, Manfred Herz planned to emigrate to Palestine and to take his brother along, at his own expense and at the risk of having to commit him to institutional care there as well. On the part of the Hamburg welfare authority and the institution in Strecknitz, there were no objections to this idea. It is not known whether Walter Herz even knew about this, nor why the emigration failed.

Based on a decree by the Reich Minister of the Interior dated 30 Aug. 1940, the "fully Jewish” patients of Northern German "sanatoria and nursing homes” were concentrated in Langenhorn in the context of the T4 euthanasia program. When Walter Herz arrived there on a collective transport from Strecknitz on 16 Sept. 1940, he met up with his brother-in-law Hans Fabian and his sister Berta again. His cousin Lilly Nathan, also ill, was spared this collection operation in the private hospital in Uelsby.

The purpose of the collection of Jewish mentally or emotionally ill patients in Langenhorn was their collective transport on 23 Sept. 1940 to the euthanasia killing center disguised as the "Brandenburg state mental institution” on the Havel River, where the 136 persons were murdered by gassing with carbon monoxide on the day of their arrival. The relatives were not informed about the actual fate of these people, nor was the Langenhorn institutional administration. One last time, Helene Herz consulted her healer, Bruno Kempe (see corresponding entry), "because of her ill children,” as the investigative transcript of the Gestapo against him reads. Due to his continued activity as a "practitioner” of the Christian Science Church, he had been denounced. Since Helene Herz was a "full Jewess,” the offense was deemed particularly serious. She never learned that her children Walter and Berta as well as Hans Fabian were no longer alive by this time.

Lilly Nathan stayed in Uelsby until the summer of 1942 and was deported from there via Kiel to the Theresienstadt Ghetto on 19 July 1942, where four days prior, her aunt Helene Herz had arrived. Helene Herz survived for only the following two months, Lilly for ten months. Both died in the ghetto.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: October 2016

© Hildegard Thevs

Quellen: 1; 2; 4; 5; 6; 7; 9; AB; StaH 133-1 III Staatsarchiv III, 3171-2/4 NR.A. 4, Liste psychisch kranker jüdischer Patientinnen und Patienten der psychiatrischen Anstalt Langenhorn, die aufgrund nationalsozialistischer "Euthanasie"-Maßnahmen ermordet wurden, zusammengestellt von Peter von Rönn, Hamburg (Projektgruppe zur Erforschung des Schicksals psychisch Kranker in Langenhorn); 314-15 Oberfinanzpräsident) R 1941/53; 213-11 Staatsanwaltschaft Landgericht 1080/44; 232-5 Amtsgericht Hamburg, Vormundschaftswesen, 429; 332-5, 1009 Nr. 368/1933, 1904 Geburtsregister Nr. 857/1877, 2846 Heiratsregister Nr. 49/1895, 3043 Heiratsregister Nr. 755/1905, 6670 Heiratsregister Nr. 290/1928, 9112 Geburtsregister Nr. 2055/1895 Herta Herz, 9134 Geburtsregister Nr. 2359/1897 Manfred Herz, 13088 Geburtsregister Nr. 1068/1899 Walter Herz, 13277 Geburtsregister Nr. 2547/1900 Berta Herz, 13404 Geburtsregister Nr. 1946/1900 Lilly Nathan; 351-11 Amt für Wiedergutmachung 1645, 3292, 11088, 20158, 39776, 352-8/7 Staatskrankenanstalt Langenhorn Abl. 1/1995 Aufnahme-/Abgangsbuch Langenhorn 26.8.1939 bis 27.1.1941, Abl. 1 Walter Herz 16190; UKE/IGEM, Archiv, Patienten-Karteikarte Berta Herz der Staatskrankenanstalt Friedrichsberg; UKE/IGEM, Archiv, Patientenakte Berta Herz der Staatskrankenanstalt Friedrichsberg; Privatpflegeheim Ülsby, Archiv, Patientenakte Lilly Nathan. Klee, Ernst, "Euthanasie" im NS-Staat. Die Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens, Frankfurt a. M. 2009. Wunder, Michael/Genkel, Ingrid/Jenner, Harald, Auf dieser schiefen Ebene gibt es kein Halten mehr. Die Alsterdorfer Anstalten im Nationalsozialismus, Stuttgart 2016. Wille, Ingo, Stolpersteine in Hamburg-Eilbek, Hamburg 2012 (Biographie Manfred, Rosalie, Ruth und Herbert Herz sowie Bruno Kempe) (siehe auch www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de). Persönliche Mitteilungen von Karla Malapert, 2008 bis 2014.

Zur Nummerierung häufig genutzter Quellen siehe Link "Recherche und Quellen".