Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Abraham Schwarzschild * 1937

Bornstraße 22 (Eimsbüttel, Rotherbaum)

1941 Riga

- Familie Schwarzschild (PDF, 3 Seiten, 406 KB)

further stumbling stones in Bornstraße 22:

Emma Cohen, Jenny Drucker, Minna Drucker, Ursula Geistlich, Selma Isenberg, Alfred Pein, Emmy Pein, Betty Schwarzschild, Sara Schwarzschild, Ignatz Schwarzschild, Rachel Süss, Clara Weil, Rosa Wolff, Bella Wolff

Schwarzschild family — great suffering and hope through committed action

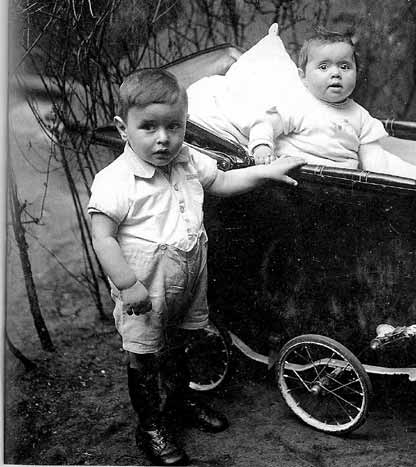

Abraham Schwarzschild, born in 1937

Bornstrasse 22 (Eimsbüttel, Rotherbaum)

Born in 1925, Schlomo Schwarzschild is the only survivor of his family and he has lived in Haifa, Israel, for more than 60 years. He remembers in considerable detail the period of his childhood and youth in Hamburg.

In a cooperative apartment house on Schlankreye, the Schwarzschilds lived openly as a religious Hamburg Jewish family in the middle of a non-Jewish environment. The father, Ignatz Schwarzschild, served as a cantor, initially at the synagogue of the Kelilat Jofi Association, located at Hoheluftchaussee 25, and subsequently, until his deportation, at a synagogue in Altona, where he worked for the community as well. He was also employed as an accountant. The mother, Kela Schwarzschild, earned some extra money toward the family’s livelihood, working as a domestic help. Until the Nazis assumed power in 1933, they were able to live with their children Salomon (Schlomo) and Leopold (Poldi) as a Jewish Hamburg family, respected by their neighbors and without discrimination. Except for their religion, which played an important role in their lives, nothing set them apart from their neighborhood. Many residents were members of trade unions and pursued Socialist goals. Ignatz Schwarzschild, too, considered himself a Socialist all his life. The family differed just as little in terms of their everyday life, e.g., their marked correctness and a penchant for order. Therefore, Schlomo Schwarzschild describes his parents as "quite German.” Nevertheless, the Schwarzschild family was not among the assimilated Jews but rather emphasized their Jewish identity. They viewed themselves as Jews living in Germany and not as Germans, conveying that sense of identity to their sons.

Schlomo was enrolled at the Talmud Tora School on Grindelhof in 1931 and Poldi in 1930. During their first years of elementary school, they were able to set out on their way to school from Schlankreye down Grindelberg and Grindelallee all the way to Grindelhof undisturbed, happy as children would be. Schlomo was eight years old when first confronted with anti-Semitic attacks. He remembers it well: "Soon after the Nazis came to power, we students of the Talmud Tora School experienced what it meant to grow up as Jews in Hitler’s Germany. On the way home from school, young Nazi rowdies often bumped into us, hurling insults at us and trying to throw us on the ground, kicking us, and tearing away our schoolbags. Grown-up passers-by rarely intervened to put a stop to the attacks.”

The schoolchildren were exhorted with an increasing sense of urgency to behave as inconspicuously as possible. After the end of classes, they were supposed to go home from the Grindel quarter as fast as they could, on their own and not in groups. In contrast to his brother Poldi, Schlomo had a hard time following the advice and not to retaliate. On the contrary, Schlomo defended himself massively, for instance, once when a Hitler youth took away his ball, saying, "Jews are not allowed to play ball.” Many a time, Schlomo fought with those attacking him and his brother because they were recognized as students of the Talmud Tora School by the other, incited children.

Schlomo’s parents got divorced when he was eleven years old. In this difficult family situation, he was sent to relatives living in Switzerland for a year. In 1937, he returned to Hamburg, once again attending the Talmud Tora School and residing with his mother in a room on Hansastrasse. In the meantime, his father had moved with his second wife Betty, son Poldi, and little Abraham, born in July 1937 into a small apartment of the Louis-Levy-Stift, a residential home at Bornstrasse 22. Betty and Ignatz Schwarzschild lived with their children in cramped conditions but among neighbors living there of their free will. In Sept. 1938, Sara was born, into an environment in which her discrimination and persecution as a Jewish girl was already a settled matter based on several hundreds of laws, ordinances, decrees, and orders.

Since the morning of 10 Nov. 1938, after the destruction and smashing of synagogues, stores, and homes of Jewish residents and the murdering of many of them, physical violence against Jews was public knowledge. Schlomo Schwarzschild recalls, "When I arrived breathless at Bornplatz, I saw the horrible sight. A crowd of people gathered. The younger ones seemed amused. The others stood around, most of them silent and with serious faces. Some grinned gleefully. Thick, black smoke billowed from the shattered windows. Torah scrolls and prayer books torn to pieces lay strewn in the piles of broken glass. For me, this moment meant the traumatic end to my childhood. It was clear to me then that there could be no future for us Jews here in Germany.”

The next day, Schlomo’s mother Kela and her second husband, Max Bundheim, immediately tried everything to be able to escape with their son and stay with relatives abroad. Despite all of their efforts, they did not succeed in fleeing anymore. In Nov. 1941, Kela and her husband were deported to Minsk and murdered there. Ignatz Schwarzschild’s family was deported from their apartment at Bornstrasse 22 on one of the first transports in 1941 and killed in Riga. Schlomo’s brother Poldi was 17 years old, his brother Abraham four years, and his sister Sara three years old.

Schlomo Schwarzschild’s parents and siblings were among the 3,162 Jewish residents of Hamburg deported to and killed in the death camps within less than two months between 25 Oct. 1941 and 6 Dec. 1941.

Schlomo did not witness the deportation of his two families anymore, because he managed to escape to Palestine. Having completed the Talmud Tora Realschule in 1939, he prevailed against his parents’ will in being allowed to attend several months of preparatory training for youths toward emigration to Palestine. Not only the solid agricultural instruction but also the training in the use of weapons for defense appealed to Schlomo, as did the idea of being able to put his adolescent energy in a development project. His mother had a very hard time letting her 14-year-old son go all by himself. However, she knew that by doing so she would give him a chance to evade the life-threatening situation in Germany.

Because he was not 15 yet (only up to 15 years was there a possibility for children to enter), and because an uncle living in Palestine took care of the formalities, since Poldi, for whom the papers had actually been issued, had already passed the age limit, and perhaps also because Schlomo was courageous, spirited, and adventurous, and, not least of all, because he was also lucky, he can today look back in Haifa/Israel on a life that brought him much suffering but turned out to be good as well. For 43 years, ships and the port of Haifa determined his working life. He fought as a volunteer in the British Royal Navy against Nazi Germany, traveled the world’s oceans on freighters for two years, and navigated the harbor tugs in Haifa for 35 years. In 1958, he married Aviva, they had two sons and one daughter, and they keep open house, lively not only when the six grandchildren are visiting.

Schlomo Schwarzschild observed events in Germany with great interest, closing his speech on Bornplatz in 1998, 60 years after 9 Nov. 1938, with the lines, "I still feel attached to the city, but I can never again ‘come home.’ In this way, I share the experience with those people who after an amputation feel imaginary pain in the severed limb. – Phantom pain. (…) Only if people intensively and resolutely fight the resurgence of Nazism is there hope for a better future.”

Karin Guth

For the Schwarzschild family, Stolpersteine are located at Schlankreye 17 (for father Ignatz, his divorced first wife Kela, and son Leopold) as well as at Bornstrasse 22 (for the second wife Betty and the children Abraham and Sara). Since Mar. 2007, that location also features a Stolperstein for Ignatz Schwarzschild.

Strictly religious, though at the same time oriented toward Socialism, Ignatz Schwarzschild served as a cantor during the 1920s and the 1930s – until Nov. 1938 – in the synagogue at Hoheluftchaussee 25. He and his wife earned a living doing accounting, trading cigarettes, cooking, cleaning, and house-sitting. The sons Salomon (Schlomo) and Leopold attended the Talmud Tora School. The Schwarzschilds were integrated in their environment, but they decidedly considered themselves "Jews living in Germany.” In 1936/37, the spouses separated. Both married new partners. Son Salomon succeeded in emigrating: He left school, completed agricultural training in Blankenese and left Germany in Dec. 1939. His brother Leopold, who had also attended the preparatory camp in Blankenese from 1938 until 1940 and learned the trade of a horticulturist from 1940 until the end of 1941, failed because of the age limit. The "Palestine Certificate” ("Palästina-Zertifikat”) that an emigrated uncle had tried hard to obtain was valid only for adolescents up to 15 years of age; thus, Leopold, born in 1924, was too old. The efforts toward emigration of his mother (married name by that time Bundheim) [author’s note: residing at Hansastrasse 57, Stolpersteine at Brahmsallee 19] and her new husband failed as well. Along with his daughter from his first marriage, they were deported to Minsk and murdered. Ignatz Schwarzschild, his wife Betty, son Leopold, and the four-year-old and five-year-old children Abraham and Sara got the deportation order sent to their last residential address at Bornstrasse 22. They ended up on the Jungfernhof farming estate near Riga, which was in no way equipped to accommodate thousands of people. Of the 4,000 Jews herded together there, almost 800 persons perished in the winter of 1941/42. However, the Schwarzschilds survived until the spring of 1942. Led into believing that they would be taken to do easier work at a fish-processing plant, some 1,700 to 1,800 persons, including the children Abraham and Sara and their mother Betty, were transported off and shot in the Rumbula forest. Ignatz and Leopold Schwarzschild had been taken along with 1,000 other men (later an additional 500) to the Salaspils camp located about 12 kilometers (nearly 8 miles) away, allegedly to build a camp where their families would follow them later. Sometime in 1942, they succumbed to the hunger, the cold, and the dreadful working conditions or they were murdered in one of the large-scale "punitive operations” ("Strafaktionen”).

Excerpt from Beate Meyer (ed.), Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933–1945 – Geschichte. Zeugnis. Erinnerung, Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, Hamburg 2006, p. 180 ff.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: January 2019

© Karin Guth, Beate Meyer