Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

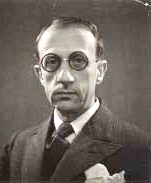

© Yad Vashem

Otto Hertmann * 1890

Justus-Strandes-Weg 4 (Hamburg-Nord, Ohlsdorf)

1941 Minsk

ermordet 18.11.1944

Otto Hertmann, born on 4 May 1890 in Hamburg, deported on 18 Nov. 1941 to Minsk, murdered in Apr. 1943 in Minsk

Justus-Strandes-Weg 4 (until 1937, Reesweg 4)

Otto Hertmann was born in Hamburg in 1890 as the son of John Hertmann (1855–1911) and Laura Hertmann, née Bergso(h)n (1859–1943). He had three siblings: Georg Hertmann (1884–1914), Karl Hertmann(1887–1915), and Anna Marie Hertmann, later married name Rössler (1892–1981). His father had acquired Hamburg citizenship in 1881 and he was co-owner of the Hamburg-based Behrens & Heimann banking business (founded in 1881 by Josef Behrens and John Hertmann/Heimann). The Hertmann family had belonged to the Lutheran Church since 1893 and officially changed the family name from Heimann to Hertmann on 17 Apr. 1903 by "resolution of a high senate” in Hamburg. With regard to the change of Jewish family names, the Hamburg Senate had decided in Oct./Nov. 1902 that "as a rule, only completely indifferent names, preferably those not borne by Christian families, would be approved (In 1902, the name Hertmann, did not exist in the Hamburg directory). The Hertmanns lived in a spacious rented apartment at Mittelweg 118 (Rotherbaum) since 1897. In the Hamburg directory entries before 1904, the family name was still "Heimann,” and only from 1905 onward was the name Hertmann printed there. The death certificate of John Hertmann showed the names of his parents: Nehemias Heimann and Line Heimann, née Schreiber. Nehemias Heimann (born on 9 May 1815 in Hamburg) worked as an accountant, and he acquired Hamburg citizenship in 1852.

Otto Hertmann’s brother Karl, born on 9 Mar. 1887 in Hamburg, studied law after graduating from high school, was a trainee lawyer from 1908, and an assistant judge in Hamburg from 1914. As a lieutenant in the reserve of Field Artillery Regiment 3, he died on the western front near Conty on 17 Mar. 1915. His brother Georg, who was an architect by profession, fell at the end of Aug. 1914. His sister Anna Marie (born on 4 June 1892 in Hamburg) married the merchant Karl Rössler (born on 7 Nov. 1887 in Werdau) in Dec. 1917 in Hamburg. He lived in Crimmitschau (Saxony) and was of the Christian faith.

Otto Hertmann attended the Wilhelm-Gymnasium, a high school emphasizing the study of the classics, from 1896 to 1908 and passed his high school graduation examination (Abitur) there in the spring of 1908; in October of that year, he began his commercial apprenticeship at the Riensch & Held import and export company (Plan 4-6, near Rathausmarkt). Due to a serious illness of his father, he quit his apprenticeship in Dec. 1910 and entered his father’s banking business. In 1910, he was deferred from the one-year military service by the draft board until 1913. He acquired the knowledge required for banking in Germany and in 1913 in Britain, working for a securities trader and a credit bank. His passport issued for Britain in Jan. 1913 is probably related to this. After the death of his father in 1911, his mother Laura Hertmann briefly took over the banking business, but the 1913 directory already listed Arthur Barden as the owner. Otto Hertmann moved up to a senior position in the banking business of Behrens & Hertmann (Adolphsplatz 6).

Since his two brothers had been drafted as reserve officers for military service and killed in action, Otto Hertmann, who had also been drafted into the Imperial Army since Feb. 1915, was transferred to the "Food Supply Office for the POW camps IX. A.K.,” a largely independent commercial position, starting in Oct. 1915.

Otto Hertmann and non-Jewish Inge Lucas (born on 21 Oct. 1902 in Hamburg) married in Jan. 1925; the couple had two daughters: Marion Susanne (born on 8 Mar. 1926) and Ruth Andrea (born on 5 Aug. 1927).The older daughter attended the Alsterdorferstrasse elementary school (1932–1935) and, from 1 Jan. 1936, Antonie "Toni” Milberg’s private school at Klopstockstrasse 17 (today Warburgstrasse/Rotherbaum); after graduating from high school, she intended to study medicine. Among the close circle of friends of Mr. and Mrs. Hertmann were the attorneys Oswald Barber (1877–1951) and his wife as well as Max Blunck.

In June 1917, the Otto Hertmann & Co. KG banking business, the successor company of Behrens & Hertmann, started operations with foreign exchange transactions and commercial banking business. Otto Hertmann was a personally liable partner; his mother Laura Hertmann, née Bergsohn, was a limited partner with an investment of 40,000 marks; Johann Theodor Köpcke and Karl Friedrich William were granted joint power of attorney. In 1921, Laura Hertmann’s capital contribution was increased by 110,000 marks and Heinrich Wilhelm Buse was granted joint power of attorney.

In the hyperinflation of 1923, Otto Hertmann’s banking operation suffered a severe capital loss. The 1924 business year also closed with a loss of 1,550 RM. Four years later, the bank official Theodor Köpcke (Oberstrasse 132) and Heinrich Wilhelm Buse entered the banking business as personally liable partners and Carl Wienecke was granted joint power of attorney; the capital contribution of his mother Laura Hertmann was converted into 40,000 RM in the course of the currency conversion. At the end of 1922, a branch office in Harburg/Elbe (Lüneburgerstrasse 32) was entered in the Harburg company register, but a foreign exchange law enacted shortly afterward prevented it from commencing operations. Only one year later, in Jan. 1926, Buse left the company; he reportedly died due to a hunting accident.

In 1929/1930, the world economic crisis also led to a massive drop in sales at Otto Hertmann & Co KG, as a result of which all employees had to be laid off and the office at Mönkedamm 8 had to be closed. In July 1934, Köpcke was forced to leave the company after embezzlement; the two remaining authorized signatories, William and Wienecke, were also deleted from the company register. According to the directory, the Otto Hertmann & Co KG banking business had its business premises at Mönkedamm 8 (1918–1936) and Neuer Wall 10 (1937). At the stock exchange, the place designation was "Pillar 62,” which had previously been used by the Behrens & Hertmann banking business.

One year after the Nazis had assumed power, in 1934, the monthly sales of securities amounted to approx. 50,000 RM, which meant that "the average monthly profit in current business was slightly over 300 RM.” Also in 1934, the former senior accountant of the bank (and since 1933 independent class lottery agent) Walter Geertz and the stockbroker Friedländer conducted negotiations with Otto Hertmann regarding the takeover of the banking business. Walter Geertz recalled 20 years later that the negotiations had failed at the time due to the bank’s unpromising economic prospects.

In the following year, the majority of Otto Hertmann & Co.’s orders were handled by the Hermann Hamberg banking house, where Otto Hertmann had been working as an authorized signatory since Sept. 1933. At the end of Dec. 1936, Otto Hertmann resigned as a member of the Association of Members of the Stock Exchange. In Feb. 1939, Otto Hertmann & Co. KG was deleted from the company register.

Otto Hertmann’s residential addresses were Mittelweg 118/ Rotherbaum (1897–1929) and Reesweg 4, on the fourth floor, in Fuhlsbüttel (1929–1936). In 1929, the Hertmann family had moved to the "still very rural Ohlsdorf” because of the children. The owner of the house at Reesweg 4 was police major Erik von Heimburg (1892–1945), who also lived on the ground floor. (In Oct. 1938, Reesweg, which had been named after the Jewish reform pedagogue Anton Rée (1815–1891) from Hamburg, was renamed Justus-Strandes-Weg. Justus Strandes (1859–1930) was an Africa merchant from Hamburg and supported the establishment of a colony in what later became German East Africa).

In 1933, after the transfer of government to Adolf Hitler by Reich President von Hindenburg, Inge Hertmann urged toward emigration. Otto Hertmann rejected this idea with the following argument: "Since my two brothers died as officers in the world war, since I myself – as the last surviving son of the family, who was sent back from the front – spent the entire world war here doing war-related work (food supply office) – since my father’s family has been resident in Hamburg for a long time ...” Contrary to hopes, the Nazi regime established itself firmly and its anti-Semitism was gradually incorporated into the laws of the German Reich.

In 1936, property manager Schulz, who, according to Mrs. Hertmann, was a staunch Nazi, gave notice without providing any reasons. The Hertmanns found a five-and-a-half-room apartment at Woldsenweg 14, which they furnished with the high-quality furnishings of the two previous residential addresses, including the dining room furnishings designed by architect Oskar Gerson (sideboard, cupboard with extension, large round table with eight chairs and flower stand – each in cherry wood with simple wood inlay), the furnishings in the study, also by Oskar Gerson (walnut or dark pear wood with tapestry covering on chairs and bench), a Chinese porcelain Buddha, an oil painting (landscape with farmhouse) by the painter Henle (probably Paul Henle 1887–1962) as well as dinner and coffee service by Copeland/England and from Meissen as well as Russian silver cutlery.

They had to give up the apartment at Woldsenweg 14 in the fall of 1938 for financial reasons and because of anti-Semitic complaints by some of the residents.

Otto Hertmann worked as an authorized signatory at the Hermann Hamberg banking business (Neuer Wall 10, fourth floor) from Sept. 1933. However, there, too, the anti-Semitic policy of destroying livelihoods led to a slump in sales, so that Otto Hertmann’s income had to be cut in half by the company owners. Walter Specht had left the company in 1935 with his investment of around 400,000 RM, emigrating to the Netherlands. In Jan. 1936, the banking operation was subsequently converted into a general partnership (offene Handelsgesellschaft – oHG), in which Julius Philip was admitted as a partner, but according to the extract from the company register, Walter Henry Specht was still registered.

An audit report of the foreign currency office dated Sept. 1938 came to the following assessment with regard to the ownership and shareholding structure: "The distribution of profits is based on 20% for Walter Specht and 80% for the partner Philip, who in turn gave sub-participation to the former bankers Otto Hertmann and Erich Friedberger with 33 1/3% each, after the two latter had made their securities clientele available to the company under review.” On 20 Oct. 1938, Customs Secretary Janssen issued a "security order” ("Sicherungsanordnung”) against the Hamberg banking business as well as its owner Julius Philip (born on 18 May 1877 in Hamburg) and his wife Irma Philip, née Specht (born on 26 June 1884 in Hamburg), as a result of which all accounts were frozen.

In Jan. 1939, the Hermann Hamberg banking business, founded in 1885, was deleted from the company register. Eventually, the clientele had also stayed away (on 19 July 1938, withdrawal of the status as foreign currency bank). The company was managed by the authorized signatory Otto Hertmann and the external auditor Friedrich Marquardt. The owners of the banking business emigrated: Walter Specht in 1935 to the Netherlands, Julius Philip in Nov. 1938 to the USA, and Erich Friedberger also to the Netherlands.

Henceforth, the Hertmann family lived from their assets and from the sale of silverware and jewelry. For eight weeks, they looked for a cheaper apartment, but most landlords no longer wanted to rent to Jews. In the fall of 1938, Fritz Warburg, who owned a house at Mittelweg 17, offered them a two-room apartment in the house next door at Mittelweg 16. Of necessity, the household of the apartment on Woldsenweg, twice as large, then had to be given away cheaply. There is no documentation as to which furnishings and works of art were lost in this way. Otto Hertmann was also registered in the May 1939 national census, which recorded Jewish residents separately, together with his wife and another twelve people at Mittelweg 16.

In order to be able to have an income again in Nazi Germany, the couple officially decided to divorce, which took place in Apr. 1939. In fact, the spouses intended to continue living together or to spend most of their time together. The divorce was intended to enable Otto’s non-Jewish wife to pursue a professional activity that she had previously been denied because of her Jewish husband. In May 1939, Otto Hertmann traveled for a few weeks to see his sister Anna Marie Rössler in Crimmitschau, whose marriage was divorced in Aug. 1939. The mother, Laura Hertmann, also lived there in the 1930s (exact details cannot be reconstructed anymore, as both the Hamburg and Crimmitschau registration files from this period no longer exist).

After his return, Otto Hertmann rented a room at Colonnaden 41 as a subtenant of the former owner of a banking operation, John Sander (born on 18 Nov. 1874 in Hamburg), and his wife Hanna Sander, née Isenberg, divorced name Marcus (born on 2 May 1886 in Hamburg), both of whom were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto on 15 July 1942.

Inge Hertmann stayed with the children in the apartment at Mittelweg 16, where Otto went daily at this time, spending only the evenings in his subtenant room. According to Mrs. Hertmann’s statement, the female Jewish resident of the house by the name of Kaufmann (deported to Lodz on 25 Oct. 1941) complained about these visits and threatened to report the divorced Hertmann couple, as she herself feared consequences resulting from the visits of the divorced couple, which were punishable by this time ("racial defilement”).

The private Milberg secondary school for girls (Rotherbaum) had to close "under the influence of the school reform, the reduction of the lower grades, and the decree to the civil servants” (school principal Bertha Schmalfeldt) at the end of the school year 1937/1938. At this time, a new secondary school had to be found for both daughters, but the state schools refused to accept new "half Jews” ("Halbjuden”). The convent school at Westphalensweg 1 (St. Georg quarter) declared itself willing to accept the new students. Daughter Marion still remembered this chapter of her history of marginalization 20 years later: "This school did indeed take us in, and my parents were very happy to be able to give us a secondary school education after all. The teaching staff (of the convent school) were touchingly loyal to us.” However, from 1942/43 onward, "half-Jewish women” like they, in the terminology of the Nazis "Jewish crossbreeds of the first degree” ("Mischlinge 1. Grades”), were banned from attending secondary schools (forced "Abschulung” [school departure”] by 30 Mar. 1943). In the case of the older daughter Marion, exclusion and stigmatization were increasingly noticeable in her school grades. From the end of the 1930s onward, Otto Hertmann tried to counteract this downward trend in school performance by constant practice with his daughter Marion.

Inge Hertmann had been working as a shorthand typist at the H. & A. Gratenau import and export company (Mönckebergstrasse 5) since 1939. In 1946, the owner of the company, August Gratenau, described the problems that arose for the company due to her inappropriate behavior: "Unfortunately, Mrs. Hertmann was very communicative. She expatiated among her fellow worker on the relations she maintained with her divorced husband, which seemed to us to be very worrying and which put her, her children, and her husband at risk. She behaved even more unwisely during the currently unavoidable and prescribed company roll calls, at the end of which, after the broadcasts via the P.A. system, the Horst Wessel song had to be sung with right hand raised. Instead of considering this a forced formality, she put the shop steward on the spot with her negative attitude, endangering our company because we were in the sights of the Gestapo and at the time, two of our owners and as well as an authorized signatory were interned in a concentration camp for up to several months.” At the end of Sept. 1938, "protective custody” ("Schutzhaft”) orders had been issued by the Gestapo in Berlin against August Gratenau and Adolf Steengrafe as well as the authorized signatory Gerhard Titzck. The Reichsstelle Chemie (Berlin) and the competitor company Flach, Muther & Co. (Hamburg) claimed a breach of fixed price agreements, but a court failed to establish this charge in 1940. The fact that H. & A. Gratenau lost all delivery orders and quota allocations was probably more crucial for the competing company.

At the end of 1938, Otto Hertmann was registered as unemployed by the Hamburg employment office; his friend Max Stierwaldt then hired him in his agency for wool and skins (at Spadenteich 1), but this was prohibited by the employment office. From 21 July 1940 onward, Otto Hertmann had to do physically strenuous forced labor ("compulsory labor”) as a cable layer and from 17 July 1940 to 9 Nov. 1940, as an excavator. When his strength was no longer sufficient, he was obliged to carry sacks in the Dr. Langer seed factory (Altona-Süd, Langestrasse) from 17 Apr. 1941. Starting on 3 June 1941, he was compelled to work for Hermann Tissies KG (in Eidelstedt, at Ottensenerstrasse 24), whose main focus was on transport; there he had to clean the plant tanks in their Eidelstedt tank farm.

Like all Jews, Otto Hertmann was also obliged to wear a "star of David” from 19 Sept. 1941, in a clearly visible manner. On 18 Nov. 1941, he was deported to the ghetto of Minsk in occupied Belarus. His wife attempted unsuccessfully to obtain the repatriation of her divorced husband from the "Jewish Affairs Department” ("Judenreferat”) of the Hamburg Gestapo (Claus Göttsche, Walter Wohlers, Stallknecht).

At the beginning of Nov. 1941, SS and police units had partially "cleared” the ghetto to the northwest of the largely destroyed city of Minsk by means of mass murders for the Jews deported there from the "Old Reich” [Altreich, i.e., Germany within the 1937 borders]. The living conditions in the ghetto were catastrophic. The old houses, by then overcrowded, lacked sanitary facilities, and in addition there was insufficient water and food supply as well as an infestation of rats. Dysentery from malnutrition, pneumonia, and frostbite led to the death of numerous camp inmates. Behind this was the soberly calculated plan to let the ghetto population die from lack of nourishment. About 900 of the 7,000 ghetto occupants were deployed in work detachments outside the camp.

In Minsk, Otto Hertmann met a former apprentice of his Hamburg banking business, who at the time was working for the Wehrmacht in a leading position in the Minsk leather factory. The latter asked the Minsk Labor Office, which was responsible for organizing forced labor, to provide him with a list of Jews who were fit for work and selected Otto Hertmann, justifying the choice with his accounting knowledge. Because of the bond with his former boss, he tried to protect him at least temporarily by a physically less strenuous job. He wrote a letter to Mrs. Hertmann in which he reported (without authorization) on her husband’s current condition and activities in the Minsk Ghetto. How long this protection lasted or, respectively, whether and when Otto Hertmann had to set out again with the Jewish forced laborer detachments is not known.

Otto Hertmann’s date of death is also unknown. The Hamburg Memorial Book entitled "Jewish Victims of National Socialism” records 18 Nov. 1944 as the date, which is also indicated on the Stolperstein laid in 2009. It is not known whether Otto Hertmann actually lived that long or whether he, like most Hamburg residents deported who survived the first year in the ghetto, was shot in a massacre on 8 May 1943: In Oct. 1943, the Minsk Ghetto was "evacuated” by the Security Police (Sipo) and Security Service (SD) of the SS. Until 1944, some prisoners survived as imprisoned forced laborers in Minsk. In the restitution file of the Hamburg State Archives, his wife stated Apr. 1943 as the period of death. In the course of the restitution proceedings, his death was officially set at the date of the German surrender, 8 May 1945.

Otto Hertmann’s 83-year-old mother, Laura Hertmann, née Bergso(h)n (born on 7 July 1859 in Warsaw), who was last listed in the Hamburg directory of 1929 as the main tenant and who had lived in Crimmitschau (Saxony) since at least July 1934, had to move to Plauen (Saxony) in Apr. 1942 on the orders of the Gestapo, where she was quartered in a "Jews’ house” ("Judenhaus”). Later she was moved to a run-down backyard factory building at Albertstrasse 18 (later Breitscheidstrasse) in Plauen, which in 1929 still housed the linen factory of Maurice Runberg and Samuel Glückmann. The "rooms” of those forcibly quartered there were separated only by sheets attached to lines. The auction of Laura Hertmann’s Crimmitschau household effects was arranged by the Lord Mayor of Crimmitschau, Franz Schmidt, and carried out by the auctioneer Alfred Trätner (Carolastrasse 4), who, according to the 1938 residents’ register, was a "local judge, legal adviser, and sworn and publicly appointed auctioneer.” Laura Hertmann was deported from Plauen to the Theresienstadt Ghetto on 29 Mar. 1943, where she died a few days later, on 8 Apr. 1943.

After her divorce (Aug. 1939), Anna Marie Rössler, née Hertmann, lost the status of a "privileged mixed marriage” ("privilegierte Mischehe”) granted by the Nazi state. She then applied for visas to the USA and Britain, but was in a less than promising position on the waiting list. Without prior notice, she was deported on 8 Jan. 1944 from Plauen (Albertstrasse 18) via Dresden to the Theresienstadt Ghetto together with 21 other residents of the "Jews’ house” in which she was quartered (Transport V/10, No. 429). All of her assets were confiscated by order of the Plauen police headquarters; the confiscation document was immediately forwarded to the Plauen District Court (Amtsgericht). Anna Marie Rössler was obliged to work for Glimmerspalterei GmbH, a mica processing company, in the Theresienstadt Ghetto starting in Sept. 1944 and she received a work permit for this purpose. She survived and managed to leave the ghetto in June 1945.

Inge Hertmann gradually fell apart due to the persecution of her family during National Socialism and the injustice of the subsequent restitution proceedings. Her daughter Marion wrote to the Hamburg "Restitution Office” ("Amt für Wiedergutmachung”) at the end of the 1950s: "Unfortunately, my mother, who had been very delicate in terms of her nerves all her life, was physically and mentally ill at that time, which then, with her having run into great financial difficulties due to long stays in hospital, had worsened. (…) On 8 Feb. 1950, my mother took her own life because she saw no way out.”

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: July 2020

© Björn Eggert

Quellen: Staatsarchiv Hamburg (StaH) 221-11 (Staatskommissar für die Entnazifizierung), 31388 (von Heimburg); StaH231-7 (Handelsregister), A1 Band 79 (Otto Hertmann, HR A 19513); StaH 231-7 (Handelsregister), A1 Band 60 (HR A 14476, Hermann Hamberg); StaH 231-7 (Handelsregister), A1 Band 197 (HR A 43640, Hermann Hamberg); StaH 241-2 (Justizverwaltung Personalakten), P 630 (Karl Hertmann, nur 1 Seite Personalbogen); StaH 314-15 (Oberfinanzpräsident), R 1938/2398 (Sicherungsanordnung gegen Bankgeschäft Hermann Hamberg); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter) 9075 u. 866/1892 (Geburtsregister 1892, Anna Marie Heimann); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter), 8006 u. 315/1911 (Sterberegister 1911, John Hertmann); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter), 8025 u. 272/1915 (Sterberegister 1915, KarlHertmann); StaH 332-5 (Standesämter), 8717 u. 263/1917 (Heiratsregister 1917, Friedrich Karl Rössler u. Anna Marie Hertmann); StaH 332-7 (Staatsangehörigkeitsaufsicht), A I e 40 Band 6 (Bürgerregister 1845–1875 G-K), Nehemias Heimann (Bürgerrecht 23.1.1852/Nr. 72); StaH 332-7 (Staatsangehörigkeitsaufsicht), A I e 40 Band 9 (Bürger-Register 1876–1896 A-K), John Heimann (Bürgerrecht Nr. 9707, 20.5.1881); StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen), K 4231 (Alte Einwohnermeldekartei 1892–1925), Eduard Bergson; StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen), K 6244 (Alte Einwohnermeldekartei 1892–1925), Anna MariaHertmann, Georg Hertmann, Karl Hertmann; StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen), A 24 Band 116 (Reisepassprotokoll 251/1913 Otto Hertmann); StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen), A 24 Band 119 (Reisepassprotokoll 3971/1913 Otto Hertmann); StaH 332-8 (Meldewesen), A 24 Band 319 (Reisepassprotokoll 994/1925 Otto u. Ingeborg Hertmann); StaH 342-2 (Militär-Ersatzbehörden), D II 139 Band 3 (Otto Hertmann); StaH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 12038 (Otto Hertmann); StaH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 26556 (Inge Hertmann); StaH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 27585 (Inge Hertmann); StaH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 47903 (Marion Sauber geb. Hertmann); StaH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 52977 (H. & A. Gratenau);StaH 430-64 (Amtsgericht Harburg), VII B 859 (Otto Hertmann& Co, 1922–1925); StaH 362-6/16 (Milberg-Schule), Sign. 2 (alphabetisches Namensregister, S. 117 Marion Hertmann, S. 118 Ruth Hertmann); StaH 731-8 (Zeitungsausschnittsammlung), A 558 (Milberg Realschule für Mädchen, 50jähriges Jubiläum 12.3.1933); Historisches Archiv Crimmitschau (Bürgermeister Franz Schmidt, Versteigerer Alfred Trätner); Stadtarchiv Plauen (Auskunft zu Laura Hertmann u. zu Judenhaus Albertstraße); Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Gedenkbuch – Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933–1945 (Laura Hertmann geb. Bergson, Otto Hertmann); YadVashem, Page ofTestimony, mit Foto (Otto Hertmann, Laura Hertmann); Adressbuch Hamburg (John Heimann/Hertmann) 1897, 1900, 1903–1905, 1907, 1910; Adressbuch Hamburg (Karl Hertmann, Referendar, Mittelweg 118) 1910, 1912, 1913; Adressbuch Hamburg (Witwe Laura Hertmann) 1912–1916, 1918, 1920, 1923, 1928–1929; Adressbuch Hamburg (Otto Hertmann) 1918–1920, 1923–1925, 1928–1938; Adressbuch Hamburg (Straßenverzeichnis) 1940 umbenannte Straßen I (Reesweg, Ohlsdorf – Justus-Strandes-Weg); Adressbuch Hamburg (Behrens & Hertmann) 1907, 1910, 1912–1916; Adressbuch Hamburg (Theodor Köpcke) 1925, 1932–1934; Telefonbuch Hamburg 1914, 1920 (Frau John Hertmann, i.Fa. Behrens & Hertmann, Mittelweg 118); Telefonbuch Hamburg 1920, 1931, 1939 (Otto Hertmann); Handelskammer Hamburg, Handelsregisterinformationen (Otto Hertmann& Co, HR A 19513; Hermann Hamberg HR A 14476 und ab 1938 HR A 43640); Hamburger Börsenfirmen, Hamburg 1910, S. 44 (Behrens & Hertmann, Bank-Comm., Inhaber John Hertmann, Adolphsplatz 6), S. 544 (Riensch& Held, gegr. 1868, Import von u. Export nach Süd- u. Centralamerika, Mexiko u. Ostasien, Inhaber Johs. W. Justus, Plan 4-6); Hamburger Börsenfirmen, Hamburg 1926, S. 445 (Otto Hertmann& Co, persönlich haftende Gesellschafter: Otto Hertmann, Joh. Theod. Köpcke u. Wilh. Heinr. Buse); Hamburger Börsenfirmen, Hamburg 1935, S. 278 (H. & A. Gratenau, gegr. 1874 in Bremen u. 1905 in Hamburg, Im- u. Export, Mönckebergstr. 5), S. 306 (Hermann Hamberg), S. 364 (Otto Hertmann& Co persönlich haftender Gesellschafter: Otto Hertmann), S. 823 (Max Stierwaldt); Frank Bajohr, "Arisierung" in Hamburg, Die Verdrängung der jüdischen Unternehmen 1933–1945, Hamburg 1998, S. 358 (Hermann Hamberg); Franz Bömer, Wilhelm Gymnasium Hamburg 1881–1956, Hamburg 1956, S. 117 (Otto Hertmann); Volkhard Knigge u.a., Zwangsarbeit. Die Deutschen, Die Zwangsarbeiter und der Krieg (Ausstellungskatalog), Weimar 2010, S. 56 (Stadtplan von Minsk mit militärischen und Versorgungs-Einrichtungen, Januar 1942); Uwe Lohalm, Die nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Hamburg 1933 bis 1945, Hamburg 1999, S. 27 (Amtl. Anzeiger 16.10.1938 Seite 802, Änderung von Straßennamen); Hans Dieter Loose, Wünsche Hamburger Juden auf Änderung ihrer Vornamen und der staatliche Umgang damit. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Antisemitismus im Hamburger Alltag 1866–1938, in: Peter Freimark/ Alice Jankowski/Ina Lorenz (Hrsg.), Juden in Deutschland – Emanzipation, Integration, Verfolgung und Vernichtung, Hamburg 1991, S. 60–63; Beate Meyer (Hrsg.), Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933–1945, Hamburg 2006, S. 64 (Exekutionen Getto Minsk); Beate Meyer, "Jüdische Mischlinge", Rassenpolitik und Verfolgungserfahrung 1933–1945, Hamburg 2007, S. 195/196 (Bildungs- u. Ausbildungsbeschränkungen); Heiko Morisse, Jüdische Rechtsanwälte in Hamburg, Ausgrenzung und Verfolgung im NS-Staat, Hamburg 2003, S. 117 (Dr. Oswald Barber); Petra Rentrop-Koch, Die "Sonderghettos" für deutsche Jüdinnen und Juden im besetzten Minsk (1941–1943), in: Beate Meyer (Hrsg.), Deutsche Jüdinnen und Juden in Ghettos und Lagern (1941–1945), Berlin 2017, S. 105–108 (Das Minsker Ghettos als Arbeitslager); Karl-Georg Roessler, No time to die. A Holocaust Survivor‘s Story, Montreal 1998, S. 27–35, 44, 49, 55–56; https://www.holocaust.cz/databaze-obeti/obet/14920-laura-hertmann/ (eingesehen 19.3.2019); https://www.geni.com/people/Otto-Hertmann/342054177330006028 (eingesehen 13.2.2018); www.census.tracingthepast.org (Volkszählung Mai 1939: Otto Hertmann, Inge Hertmann geb. Lucas, eingesehen 7.3.2018); www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de (John und Hanna Sander).