Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

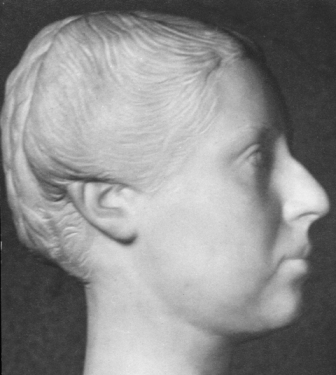

Dr. Olga Herschel * 1885

Oderfelder Straße 13 (Eimsbüttel, Harvestehude)

Freitod am 17.11.1938 HH

Dr. Olga Herschel, born on 15 Mar. 1885 in Hamburg, suicide on 17 Nov. 1938 in Hamburg

The Hamburg ophthalmologist Dr. Wolfgang Herschel (1855–1913) and his wife Sophie, née Warburg (born on 5 Apr. 1862) had been married in June 1884. Sophie Warburg was the daughter of the merchant and Hamburg citizen Siegmund (formerly Simon) R. Warburg (1817–1899), co-owner of the silk company R. D. Warburg & Co., which had branches in Zurich, Paris, and Lyon, and Anna, née Goldschmidt (1833–1894). Her brothers Rudolph D. Warburg (1857–1902) and Otto Warburg (1859–1938) completed their schooling with the high-school leaving certificate (Abitur).

The family lived at Mittelweg 151. While Rudolph Warburg joined his father’s company as a partner in 1888 after a commercial apprenticeship and a one-and-a-half-year trip around the world, Otto Warburg studied botany and afterward traveled in East Asia for study purposes for four years. He became active in the Zionist movement. They were related only very distantly to the bankers Max Warburg (1867–1946) and Fritz Warburg (1879–1964), as well as Professor Aby Warburg (1866–1929).

The marriage of Wolfgang and Sophie Herschel produced the two daughters Olga (born in 1885) and Anna Ottilie (1888–1904). Since 1893, they grew up in the immediate vicinity of the Alster River in a ground-floor apartment located at Alte Rabenstrasse 34 (Rotherbaum), a street laid out 35 years before. Wolfgang Herschel’s ophthalmologist’s practice was located at Bergstrasse 6 (Hamburg-Altstadt) until 1905 and was then relocated to Neuer Wall 5 (Hamburg-Neustadt). In 1964, Paul Wohlwill observed that Olga Herschel "inherited from her father a markedly patriotic disposition.”

The interest in history, too, may have been set by example, for the father was a member of the Patriotic Society (Patriotische Gesellschaft) in Hamburg since 1905. Financially secure due to her family background, Olga Herschel was able to dedicate herself to her inclinations: national politics and national culture. Contact to the poet Richard Dehmel (1863–1920) had intensified to such an extent after his comedy Michael Michael, which premiered at the Deutsche Schauspielhaus in Hamburg on 11 Nov. 1911, that since mid-1912 Olga Herschel and Emmy Auguste Wohlwill served as main initiators in collecting donations for his new domicile in Blankenese from well-to-do friends, including Walther Rathenau (1867–1922), from 1915 onward president of the AEG Electrical Corporation and in 1922 German foreign minister as member of the German Democratic Party (DDP), Josef Winckler (1881–1966), the Westphalian poet, as well as Albert Ballin (1857–1918), the director general of the Hamburg America Line (HAPAG).

Olga Herschel brought good skills to this mediatory role between financially strong figures, whom she knew from her family, and literary personalities, whose artistic-societal work she deemed important. Since this time, she was close friends with the Jewish wife of the poet Richard Dehmel, Ida Dehmel, née Coblenz (1870-1942). The two also agreed politically.

The death of the father in 1913 brought far-reaching changes in the lives of the wife and daughter: About one year after his death, Olga Herschel’s mother left the Jewish Community, and Olga Herschel had herself baptized as a Protestant in Nov. 1916.

In Oct. 1913, only a few weeks after the death of her father, she began studies of medieval and modern history at Ludwig-Maximillian-University in Munich. She took, among others, courses in economic history (with Prof. Dr. Lujo Brentano), source studies and document reading (with Hellmann), general history of the seventeenth to the nineteenth century (with Marcks), as well as history of the German imperial period (with Prof. Dr. Hermann von Grauert), which required payment of fees depending on the weekly number of hours. In an evaluation, Professor von Grauert described her as an "astute mind.”

She was a member of the "Association of Women Students” ("Verein Studentischer Frauen”) and possibly obtained living quarters via this avenue. Olga Herschel did her Ph.D. in Munich on the topic of Die öffentliche Meinung in Hamburg in ihrer Haltung zu Bismarck 1864–1866 ("Public opinion in Hamburg in terms of its attitude toward Bismarck 1864–1866”); the oral exam took place on 11 Dec. 1915, and in 1916, her 80-page doctoral thesis appeared with Boyens Publishers in Hamburg. Even the independent Mayor Werner von Melle (1853–1937), a school friend of Olga Herschel’s father, commented on her dissertation.

It is no coincidence that she chose one of the Conservative figureheads as a topic for her dissertation; after all, even during her university days, she already included herself among the conservative-nationalist camp. In the years ensuing, articles authored by her repeatedly appeared in various newspapers, though no overview exists to date. Two examples: In Dec. 1929, Olga Herschel published in the Hamburg University Newspaper an obituary entitled "Erinnerungen an Professor Aby Warburg” ("Remembering Professor Aby Warburg”), and in Nov. 1924, she reported in a newspaper about a lecture by the völkisch lyric poet Maria Kahle (1891–1975).

After the end of World War I and the abdication of the German emperor, Olga Herschel joined the conservative German People’s Party (Deutsche Volkspartei – DVP) in Hamburg, where she belonged to the right wing from then on. The DVP had emerged from the pro-Bismarck National Liberal Party founded in 1867, and during the initial years of the Weimar Republic, the party was monarchist in orientation. Olga Herschel became active in, among others, the women’s committee of the DVP and reported on it in the DVP’s Nachrichtenblatt dated 25 Nov. 1920 under the heading of "Eine Aufgabe für Frauenausschüsse” ("A task for women’s committees”).

Her relationship to the new democratic system of government in Germany was – similar to that of the DVP – not untroubled: "It is characteristic of her attitude that she congratulated the Kaiser year after year. The letter of thanks with the emperor’s picture was on her desk all those years,” recalled Paul Wohlwill in 1964. Her friend Ida Dehmel also temporarily became active for the DVP, which she had joined in Nov. 1918. Until Sept. 1920, she even belonged to the acting Reich Executive, from 1922, she was a regular party member; as a national patriot, her husband Richard Dehmel had sung the praises of the First World War in verses.

From 1924 until 1932, the DVP in Hamburg participated in a coalition government consisting also of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP). In the 1920s, Olga Herschel vehemently advocated the rearming of the German military. In the 1928 Hamburg directory, she was listed with the addition of "Dr. phil., independent scholar.” At this time, she continued to live at Alte Rabenstrasse 34 with her mother, who died on 28 Mar. 1929.

The DVP, Olga Herschel’s political home, disintegrated in the entire German Reich as of 4 July 1933, after political institutions had already been "forcibly coordinated” ("gleichgeschaltet”) by the Nazis before. In Hamburg, the executive bodies of the DVP had decided by a majority as early as 12 Apr. 1933 that their members ought to go over collectively to the Nazis, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party [NSDAP] – nearly 75% of party members followed this resolution. With the "Law against the Formation of New Political Parties” ("Gesetz gegen die Neubildung von Parteien”) dated 14 July 1933, the NSDAP secured its monopoly position also in a pseudo-formal way. Probably in 1936/1937, Olga Herschel moved to Oderfelder Strasse 13 (Harvestehude).

Whereas as late as Aug. 1936, she had written with national emotionalism from the Island of Helgoland, "I enjoy every piece of artillery [in the context of rearmament] as a resurrected friend,” two years later the administrative authority of the health resort denied her the vacation stay. "In response to your obliging inquiry dated 9th day of this month, we most humbly inform you that the visit of our spa by Jews is not welcome. Heil Hitler! Administrative Authority of the Helgoland Health Resort.” The rejection letters by the Hiddensee and Cuxhaven resorts were almost identical in content. The patriotic German woman was reduced by the Nazi rulers to her Jewish descent, classified as "alien to the [German] people” ("volksfremd”), and ostracized. Swimming, too, something she practiced on a regular basis for physical strengthening, was made impossible for her. Jews were banned from using swimming pools from about June 1937; large signs at swimming pools indicated this ban. (From Dec. 1938 onward, a police order prohibited Jews from visiting public and private spas as well as cultural institutions.)

As late as fall of 1937, she had regarded the emigration of a female cousin as a "betrayal of Germany.” However, gradually it dawned even on the committed nationalist and religious Protestant that the National Socialist German state shaped its "[German] national community” ("Volksgemeinschaft") in violent segregation from its self-proclaimed enemies, in whose ranks she, a woman of Jewish descent, was included as well.

During the November Pogrom of 1938, violence escalated, and afterward, a new phase of rightlessness and lawlessness was initiated. The only thing granted to Jews or, respectively, persons declared to be Jews by the Nazis, was emigration. Olga Herschel was not willing to take that avenue. On 13 Nov. 1938, she wrote a farewell letter. The two-page letter was addressed to "Dear relatives and friends” and in it, she calmly explained her decision to commit suicide. The pain at being condemned to doing nothing, when energy and will were certainly there, resonated as she wrote, "[I]n the last ten years, during which life was without immediate duties for me, I have on various occasions had thoughts of voluntary death, contemplating it in earnest dialog with God. However, I always had the feeling until the end that God had not opened up that path for me yet. Today it is different. Today, as I can no longer respect my fatherland, which I love more than anything, this barrier has fallen. Yes, I do have the firm feeling that God Himself points the way for me, and I will go that way.”

Olga Herschel tied the rope herself with which she intended to take her life. On 17 Nov. 1938, one week after the pogrom, she hanged herself at the age of 53 from the mullion and transom of her bedroom window at Oderfelder Strasse 13. As early as eight years before her suicide, she had decreed that the pastor should hold the funeral oration for her about I Corinthians 16:13 from the New Testament: "Watch ye, stand fast in the faith, quit you like men, be strong!”

Paul Wohlwill (1870–1972), retired Associate Judge at the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgerichtsrat) and second cousin, took care of the deceased’s estate.

On 27 Dec. 1938, a payment notification to the effect of 38,000 RM (reichsmark) in "atonement payment” ("Sühnezahlung”) was addressed to Olga Herschel, and only in Feb. 1939, the authorities realized that Olga Herschel had already passed away.

In Aug. 2009, a book Olga Herschel had owned (Görries, Die heilige Allianz und die Völker auf dem Congresse von Verona, 1822) was offered for sale in a Swiss second-hand bookshop. The store pointed in particular to the ex libris by Olga Herschel glued into the volume and provided a few biographical details about the book’s former owner for better contextualization.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: October 2016

© Björn Eggert

Quellen:

Hamburger jüdische Opfer des Nationalsozialismus. Gedenkbuch, Hamburg 1995, S.161; Staatsarchiv Hamburg (= StaHH) 231-3 (Handelsregister, bis 1908), B 14612 (R.D.Warburg & Co., 1848, 1850, 1879); StaHH 314-15 (Oberfinanzpräsident), R 1939/761 (Hypothekenrückzahlung an Olga Herschel, 1939); StaHH 314-15 (Oberfinanzpräsident), R 1939/2378 (Sicherungsmaßnahmen); StaHH 332-8 (Alte Einwohnermeldekartei), Dr. W.A. Herschel, Siegmund Rudolph Warburg; StaHH 351-11 (Amt für Wiedergutmachung), 150395 (Mathilde Schneider); Hamburger Adressbuch 1902, 1928; Amtliche Fernsprechbücher Hamburg 1897-1913 (Dr. W.A. Herschel), 1925-1928 (Frau Herschel), 1929-1937 (Dr. O. Herschel); Jahrbuch der Hamburgischen Gesellschaft zur Beförderung der Künste und nützlichen Gewerbe /Patriotische Gesellschaft, Hamburg 1913, S.59 (Dr. W. A. Herschel); Lieselotte Resch /Ladislaus Buzàs, Verzeichnis der Doktoren und Dissertationen der Universität Ingolstadt – Landshut – München 1472-1970, Philosophische Fakultät 1750-1950, Band 7, München 1977, S.211 (Olga Herschel, U 16.1898); Maximilians Universität München, Promotionsakte (UAM, O-II-3p), Studentenkartei I Herschel, Olga, Verzeichnis der Honorarzahlungen; Online-Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek, Dissertation von Olga Herschel; Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg (SUB), Literaturarchiv (LA): Herschel, Olga (u.a. Abschiedsbrief vom 13.11.1938 u. Lebenslauf erstellt von Dr. Paul Wohlwill, 1964); Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg (SUB), Literaturarchiv (LA): Kahle, Maria : 3 (kurzer Dankesbrief an Olga Herschel, 4.12.1924); Matthias Wegner, Aber die Liebe – der Lebenstraum der Ida Dehmel, München 2000, S. 270, 272, 367 (Olga Herschel), S.343, 355 (DVP); Helmut Stubbe – da Luz, Die Stadtmüter Ida Dehmel, Emma Ender, Margarethe Trenge, Hamburg 1994, S.28-30 (Ida Dehmel und die DVP); www.loebtree.com/warburg.html (eingesehen 12.5.2009); Raffael Scheck, Mothers of the nation – right wing woman in Weimar Germany, Oxford 2004, S.148, 155 (Olga Herschel); Eva Schöck-Quinteros /Christiane Streubel (Hrsg.), Ihrem Volk verantwortlich – Frauen der politischen Rechten (1890-1933), Berlin 2007, S. 169 (DVP-Frauenausschuss, Herschel); Ursula Büttner /Werner Jochmann, Hamburg auf dem Weg ins Dritte Reich – Entwicklungsjahre 1931-1933, Hamburg 1985, S.63/64 (DVP); Ferdinand S. Warburg, Die Geschichte der Firma R. D. Warburg & Co., ihre Teilhaber und deren Familien, Berlin 1914, S. 12-34; E-Mail von Herrn M.W. (Israel), August 2009; Wolf Gruner, Judenverfolgung in Berlin 1933-1945. Eine Chronologie der Behördenmaßnahmen in der Reichshauptstadt, Berlin 1996, S.43 (Badeanstalten).