Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

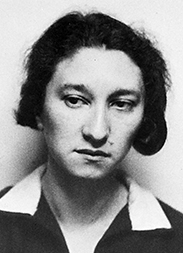

Ruth Kantorowicz * 1901

Eimsbütteler Chaussee 63 (Eimsbüttel, Eimsbüttel)

HIER WOHNTE

DR. RUTH KANTOROWICZ

JG. 1901

FLUCHT 1936

HOLLAND

INTERNIERT WESTERBORK

DEPORTIERT 1942

ERMORDET IN

AUSCHWITZ

Dr. Ruth Renate Friederike Kantorowicz, born on 7 Jan. 1901 in Hamburg, deported on 7 Aug. 1942 to Auschwitz, died there probably on 9 Aug. 1942

Eimsbütteler Chaussee 63

For nearly 34 years, Ruth Kantorowicz lived on Eimsbütteler Chaussee. She was born in house no. 27. In 1916, her family moved to house no. 63 and in 1932 further to house no. 124. House no. 63 had been built as Hamburg’s first permanent movie theater in 1910 and was known all over town. The doctor’s practice of her father was located on the second floor above the movie theater auditorium. Thus, the secondary student Ruth intensively experienced cinematic art in its pioneering days. The movie theater building exists to this day, whereas houses nos. 27 and 124 were destroyed by bombs.

Ruth’s special areas at school fit well with the modern world of the movies. Her teachers assessed her performance in biology, physics, chemistry, and singing with very good grades. A handwritten comment in her high-school diploma (Reifezeugnis) dated 3 Feb. 1921 says, "Miss Kantorowicz received a copy of the Reich Constitution.” The constitution had been in effect for a mere year and a half, stipulating for the first time, "All Germans are equal before the law.” (Par. 109). Accordingly, in her school-leaving certificate, a faint line behind "religious instruction” was the only clue to the fact that this student belonged to a religious minority.

At the time, Eimsbüttel was a new housing development and many inhabitants came from outside of Hamburg. For instance, Ruth’s father, the general practitioner and obstetrician Dr. Simon Kantorowicz, was a native of Posen (today Poznan in Poland), a large Prussian city characterized mostly by Polish influences. In 1894, he had sworn the Hamburg citizen’s oath. Young physicians happened to be very welcome on the Elbe River due to the cholera epidemic the city had just overcome. Ruth’s mother, Hulda Friedheim, was a native of Hamburg and Ruth would be their only child.

An early childhood episode deserves mentioning in somewhat more detail: When Ruth was four years old, she met for the first time the Breslau native Edith Stein, who would later become a role model and support for her, a woman Catholics have been worshipping as a holy martyr since 1998. Edith Stein was nine years older than Ruth and for one year, as a 14-year old, she had lived on Eimsbütteler Park (at Ottersbekallee 6) with her married sister (Else Gordon), whose husband was a colleague of Ruth’s father, Simon Kantorowicz. Edith became a philosopher and the first assistant of the influential thinker Edmund Husserl (a phenomenologist), who awarded her a doctoral degree. In 1922, she had herself baptized, after years spent distant from religious beliefs. The scholar’s attempt to obtain her postdoctoral qualification (Habilitation) failed in Göttingen, Freiburg, and Breslau – probably because she was a woman and of Jewish descent. She left behind a well-regarded and extensive oeuvre to which Ruth Kantorowicz was able to contribute a modest share starting in 1935.

In the second year of the existence of Hamburg University, Ruth enrolled in two faculties: Law and Political Science as well as Mathematics and Natural Sciences. The teacher who would become her mentor was the first full professor of Theoretical Economics in Germany, the economic-liberal Heinrich von Gottl-Ottilienfeld, whom she later followed to Kiel and Berlin. It took a lot of courage to dare venture into this male preserve. During her time in Hamburg, she devoted an unusual degree of thoroughness to practical skills: In 1922, she worked at the Unterelbe Tax Office during her semester break; afterward, employed with Deutsche Bank for 12 months, she experienced the hyperinflation of 1923 and its mastery. In mid-1930, as a logical consequence, she received her doctorate in Berlin for a thesis on Die Wirklichkeitsnähe nationalökonomischer Theorie ("Sense of realism of economics theory”) "with great distinction,” magna cum laude. Even while still a doctoral candidate, Ruth already started an internship at the business editorial department of the Kasseler Tageblatt. Hard to comprehend that the highly qualified woman already changed four months later to become a secretary at the Pädagogische Akademie Cottbus, an educational academy in Cottbus, and, when this institution had to close, for a brief period to a corresponding position in Frankfurt/Main for slightly under 200 RM (reichsmark) a month. From 1930 until 1932, the world economic crisis depressed the country. In Hamburg, every second man became unemployed and the city nearly insolvent. A look at the Jewish religious tax (Kultussteuer) card file of the Hamburg Jewish Community reveals that the parents only had very little money at their disposal by then. In 1930, the father, who had earned a good income before, and the daughter were assessed there with only 15 RM. Therefore, the father was unable to contribute anything to the expensive doctoral studies outside of Hamburg.

This was the beginning of a series of more terrible strokes of fate: In Apr. 1932, death released the mother "from agonizing sufferings.” Daughter and father left the doctor’s practice and residential quarters, moving to more affordable accommodation. In October of that same year, the economist with a doctorate had to be satisfied with a traineeship with the Hamburg Öffentliche Bücherhallen ("public book halls”) to do "service in the popular books libraries,” from which she was already dismissed again, however, in 1933 for being Jewish. Ruth found a job as an office worker in a pencil factory (Schüler & Co.). From her small income, she was forced to support her father as well, who by then had become destitute. When she lost this position, too, after six months, she was left with no more than 100 RM a month.

The father died in the hospital of the Jewish Community (at Eckernförderstrasse 4) in Sept. 1934. Ten days before – on 8 Sept 1934 – Ruth had herself baptized. Father Karl Joppen administered the sacrament in the Catholic St. Elisabeth’s Church in Harvestehude. Father Joppen belonged to the Hamburg branch of the Jesuits, who supported the persecuted Jews in the Grindel quarter "with great vigilance, cleverness, cunning, circumspection, and care.”

One cannot help but think that perhaps grief about the baptism caused the father’s death. Edith Stein provides the answer in her letter of condolence dated 4 Oct. 1934: "That for your dear father, your conversion was a source of joy is a special grace for you and for him.” After decades, this letter re-established contact. The letter also stated, however, "By way of my sister … I was always informed about your external development and you probably about mine as well.” A total of 49 letters document that the connection was intensive and remained active until both of their deaths.

In Oct. 1933, after extended preparations, the baptized philosopher Edith Stein had become a Carmelite nun in Cologne. In this contemplative enclosed order, the nun bore the name of Teresia Benedicta a Cruce from that time onward. Ruth intended to follow her on this path and spent Christmas of 1934 in Cologne. In the summer of 1935, she moved there for good, to Classen-Kappelmann-Strasse 14. After the Cologne Carmelite order had refused her admission, one year later Sister Benedicta succeeded in placing Ruth as a postulant in the Carmelite order in Echt near Maastricht (Netherlands). She was greatly worried about her depressed and sickly protégé, writing "We must pray again now, however, that strength will suffice.” After a year, when the Dutch nuns also decided against the novitiate following the postulate, Sister Benedicta wrote to a confidante, "Just how helpless and at a loss the poor creature probably is over there …” Ruth’s father confessor, the Steyler Missionary Father Heinrich Hopster, reported after the war: "… she had to leave the convent because she was much too weak physically.” He also wrote, "… I have rarely seen a human being who was so scared.” Later, she also suffered from rheumatism. Ruth wrote to Sister Benedicta: "The nights are fatal as I am in a lot of pain when lying down.”

Eventually, the nun managed to accommodate Ruth as a "maid of all work” in the Ursuline convent (teaching order) in the Dutch town of Venlo, and in 1938, Sister Benedicta came into Ruth’s vicinity, when the Carmelite nun fled to the Carmelite order in Echt after the November Pogrom of 1938 in Germany. Now, for both of them four years of prolific collaboration began, without which it would not have been possible to publish the 26-volume oeuvre of the philosopher in the future. During this time, Ruth transcribed with a typewriter thousands of poorly legible manuscript pages of the Catholic saint.

The end approached when the archbishop of Utrecht, Jan de Jong, in close cooperation with the Protestant churches of the Netherlands, had a pastoral letter against the persecution and deportation of Jews read from all Catholic pulpits on Sunday, 26 July 1942. The Gestapo had learned about the plan early on, threatening the archbishop, who would not be put off, however. As early as the following Monday (27 July 1942), the "commander of the Security Police and the SD [Security Service] for the occupied Netherlands” issued the following directive:

"Since the Catholic bishops have meddled – without being affected themselves – in the matter, all of the Catholic Jews will now be deported within this week … On Sunday, 2 Aug. 1942, Commissary General [Generalkommissar] Schmidt will give a public reply to the bishops at a party event in Limburg.” The Deutsche Zeitung in den Niederlanden reported on 3 Aug. 1942, "… Hauptdienstleiter [‘Head Service Leader,’ a senior party rank] Schmidt spoke … If, however, the Catholic clergy disregards negotiations in this way, we in turn are forced to regard the Catholic full Jews as our worst enemies and ensure their transport to the East as fast as possible. That has happened.”

Indeed, on Sunday all Catholics of Jewish descent of whom the SS and Gestapo managed to get a hold were arrested, 244 overall. They perished a week afterward, on the day of their arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: October 2016

© Dietrich Rauchenberger

Quellen: 1; 4; StaH 332-5 Standesämter 1024, Nr. 360 - 8115, Nr. 172 – 8605, Nr. 89 – 13620, Nr. 89; Karmelitinnenkloster Maria vom Frieden in Köln (Hrsg.), Edith Stein-Gesamtausgabe, Bd. 1, 3. Aufl., Freiburg 2010; Bd. 2, 3. Aufl., 2010; Bd. 3, 2. Aufl., 2006; Nachlass Dr. Ruth Kantorowicz (Kopien Archiv Elisabeth Prégardier, Oberhausen; Nachlass Edith-Stein-Stiftung Köln); Holde (Friedenau), Kondolenzbrief an Ruth Kantorowicz v. 21.4.1932, Kopie Archiv Elisabeth Prégardier; Heinrich Hopster, Brief v. 23.4.1949 an die Priorin des Karmelitinnenklosters in Köln (Bericht des Beichtvaters von Ruth Kantorowicz über die Jahre 1940–1942, Kopie Archiv Elisabeth Prégardier); Robert M. W. Kempner, Edith Stein und Anne Frank; Elisabeth Prégardier, Gefährten – Edith Stein; Elisabeth Prégardier, Dr. Ruth Kantorowicz; Clemens Thoma.