Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Walter Schulz * 1928

Kegelhofstraße 14 (Hamburg-Nord, Eppendorf)

HIER WOHNTE

WALTER SCHULZ

JG. 1928

VERHAFTET 8.10.1943

GEFÄNGNIS HERFORD

TOT 10.5.1945

Walter Richard Otto Schulz, born 18.1.1928 in Hamburg, arrested on 8.10.1943, sentenced on 6.1.1944 by the Special Court at the Hanseatic Higher Regional Court, died on 10.5.1945 in the Catholic Hospital Herford

Kegelhofstraße 14 (Hamburg-North, Eppendorf)

Towards the end of the fourth year of the war, on October 4, 1943, at about 8:30 p.m. - darkness reigned on Hamburg's streets because of the blackout order - a group of five youths attacked two uniformed Hitler Youths. They were just leaving the house of their unit (the HJ-Bannhaus) at Loogeplatz 14 in Hamburg Eppendorf. The HJ belonged to the HJ's patrol service and wanted to check their territory. Before they realized it, they were covered with blows from their fists, went to the ground, and received a few more violent kicks.

The five attackers made off to their usual meeting place at the tube bunker (Röhrenbunker) at the intersection of Lokstedter Weg and Tarpenbekstraße. There they met other youths. The mood was excellent after the successful lightning strike.

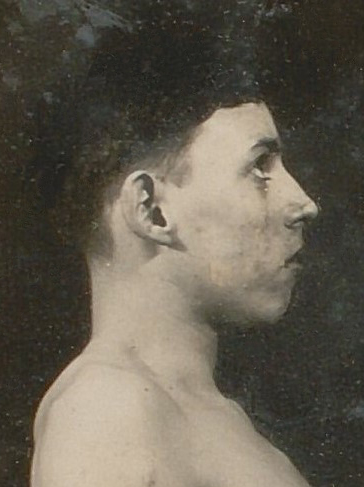

The assembled boys belonged to the 1926 to 1928 cohorts, i.e. were 15 to 17 years old. They all came from the more modest neighborhood of Eppendorf between Tarpenbekstraße, Lokstedter Weg, Frickestraße, Niendorfer Straße (today's Geschwister-Scholl-Straße). Their parents were workers and small employees, they themselves were apprentices in industry or handicrafts or did simple wage labor. Among them was Walter Schulz (born 18.1.1928), a young worker. He was later hit hardest by the revenge of the Nazi justice system.

Strengthened by their success, the HJ opponents tried to extend their victory even further. First in a disguised voice, then using his full name and HJ rank, one of them, the locksmith apprentice Karl-Heinz Soost (born 24.2.1926), HJ-Oberrottenführer and member of the HJ-Motorradgefolgschaft Nord, called from a telephone booth in the "Bannhaus" and reported with emphasis in his voice the "gathering of bawling and rampaging semi-strong Teenager" ("Halbstarke”) at the Röhrenbunker. In the "Bannhaus" however one recognized the trap and sent a larger troop of strong lads off. The clique at the tube bunker dispersed, there were chases and isolated brawls in the streets where the HJ opponents lived. In the process, one of them was arrested and initially taken to the "Bannhaus".

The Eppendorf clique tried it again in a similar way the next night, October 5. But this time the police were forewarned, and when some officers arrived, the youths quickly scattered in all directions, so that the police left empty-handed. Over the next few days, however, the troublemakers were arrested one by one, eventually numbering ten. Some of them had been recognized by the HJ-men, others had given names in the interrogation. Two Gestapo men arrested Walter Schulz on October 10 in his parents' apartment at Kegelhofstraße 14. So the Gestapo was involved. That did not bode well.

Walter's mother recalled after the war: "He was picked up with the remark that he should only come along to make a statement and would be back with us in the evening at the latest! After a long and fruitless search, I received the first notification of his whereabouts in November from the remand prison, where I was allowed to visit him once. There he had a thick spot smeared with ointment on the top of his right eye, as well as on his left cheek, which was very swollen. When I asked him about the origin of the wounds, he could not answer me, because an official was present during the visit! ..."

But what had motivated the adolescents, in Nazi propaganda the "guarantors of the future," to attack the HJ, especially the patrol service? They had all had direct or indirect experience with the HJ, at the latest since membership in the HJ or the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM) had become compulsory in March 1939. As today's research shows, the constant drill, the obtuse being ordered around, the increasing service obligations in the escalating course of the war, the ever tougher pre-military exercises, the suppression of any initiative in the gathering of young people, aroused increasing reluctance, even hatred, for the institution of the HJ and especially for the patrol service (SRD). Its role had been continually strengthened during the war by a series of decrees: The SRD had the task of monitoring the lives of young people outside the HJ, taking action against independent gatherings - as here at the tube bunker - and reporting deviant behavior to the police and the Gestapo. The HJ patrol maintained close contact with the Gestapo and also with the SS, whose reservoir of new recruits it was seen as. An attack on the patrol service was thus indirectly an attack on a central institution of the Nazi violent regime.

The tube bunker group was not the only one of its kind in Hamburg, but it was probably the last to be crushed. Since 1941/42, a whole series of comparable groups had formed in other parts of the city in the more modest social milieus, for example in Eimsbüttel ("Die Pfennigbande"), Barmbek, Altona or Hoheluft. They also existed in other large cities such as Munich ("Die Blasen"), Leipzig ("Die Meuten"), Krefeld or Cologne, where they counted themselves among the "Edelweiss Pirates."

All of the Hamburg groups had emerged from convivial, peaceful after-work gatherings of young people in a particular square or street corner of their neighborhood. It was not until the persistent harassment by the HJ patrols that they joined together more firmly and wanted to do something about their oppression. There were no political goals in the strict sense. The various groups had little or no contact with each other; they were too unstructured for that. What they had in common was that they were born before 1933, but they experienced their youth during the Nazi era. As a youth organization, they really only knew the Hitler Youth or the clubs that were aligned with it. There were no more alternatives.

Where were the adolescents supposed to find orientation and support in their rage? The Eppendorf boys did not come from academically educated homes; they could not study philosophy and political issues at university or college like the Scholl siblings and their fellow students. The followers of the Hamburg Swing Youth, on the other hand, almost all came from well-to-do backgrounds and could afford to get together in their cultivated oppositional style, although that was also dangerous. Only a few youths, like Helmuth Hübener (8.1.1925 - 27.10.1942), who was executed at the age of 17 (see www.stolpersteine-hamburg.de), developed their resistance on their own initiative; they are highly impressive exceptional phenomena.

But what the boys from Eppendorf and also the other boys from Hamburg - girls were not represented at all in such actions as those against the HJ patrols - knew was violence. They knew it from their families, from school, from work, from the HJ. Violence determined the Nazi social system anyway, and the war of extermination had an effect on German society. So one, if not the formative experience of their young lives was violence. A few months before their action against the HJ patrols, large parts of Hamburg had been reduced to rubble in June/July 1943, and tens of thousands of people had been injured or perished. Why shouldn't they dig in and kick in in their rage, perhaps even in their desperation?

In any case, the Nazi justice system struck without pardon. All the Hamburg groups mentioned above were rooted out, those involved were sentenced in some cases to long prison terms, and some of them were subsequently sent to the front on death squads, which they did not survive. An instruction from the Reich Main Security Office (dated 25.10.1944) stated: "Surveillance and combating of the cliques are important for the war.

After several months of pre-trial detention, the ten people arrested from the tube bunker stood before the Special Court of the Hanseatic Higher Regional Court on January 6, 1944. Their trial bore the file number 11 Js. P. Sond. 411/43 (38c) Sond. Ger. 253/43. The "P" indicated that the attack on the HJ patrol was considered a political offense (as opposed to V/Volksschädling or W/Wirtschaftsverbrechen). The special court made short work of the case in the truest sense of the word. The indictment was not available to the defendants until the day of trial. Defense counsel could be appointed only with the court's approval. Exculpatory witnesses could not be called, motions and appeals against the verdict could not be filed.

The indictment read: "The defendants joined forces on the street in order to jointly prevent the HJ patrol from carrying out the control activities incumbent upon it under the police regulations for the protection of youth. In doing so, they jointly maltreated members of the patrol and members of the Hitler Youth by means of deceitful assault, the defendant Schulz also by means of a dangerous tool... They thus participated in an association whose purposes and occupations include preventing measures of the administration by unlawful means...".

That sounded like endangering the state. Walter Schulz, along with Günther Pehlcke (born 18.4.1926) and Karl-Heinz Soost (born 24.2.1927), was also classified as "founder and head" of the "association". By the "dangerous tool" with which Schulz was furthermore supposed to have abused the patrol HJers, the metal fittings on the heels of the shoes were meant, which were common at that time to protect the soles from wear and tear.

Walter, who had just turned 16, was hit particularly hard: youth prison for an indefinite period, but at least for one year and three months. When he would be released depended on the goodwill of the prison officials and the juvenile authorities. In addition, it was stipulated: "On release, return to the Gestapo.” Walter was also accused of having been in a camp for Polish forced laborers four or five times in December 1942 and of having made contact with one of them, which Walter admitted.

Günther Pehlcke was somewhat less badly hit: imprisonment for an indefinite period, but at least one year. The sentences of the others ranged from six to two months in prison and four weeks of youth detention. Günther's brother Bruno Pehlcke (born 1913), who had not been involved in the nocturnal actions, was sentenced to 1 ½ years in prison for aiding and abetting grievous bodily harm because he had "incited the juvenile defendants to their assaults."

Walter was transferred from the Hamburg remand prison to the Herford juvenile prison on February 7, 1944, as was Günther Pehlcke. For Walter Schulz, the minimum prison sentence would have ended on January 4, 1945, for Günther on October 8, 1944.

The juvenile prisons of the Nazi era can hardly be compared with those of today: after 1933, they - including the one in Herford - increasingly took on the character of penitentiaries.

What is known about Walter Richard Otto Schulz's life from the time before his conviction? He was born - as mentioned - on 18.1.1928 as the son of the motorist Richard Otto Schulz (born 12.2.1896 in Rathenow/ Westhavelland) and Martha Augusta Schulz, née Schlobohm (born 13.10.1907 in Hamburg), and had three younger siblings: Anneliese Martha (born 30.3.1931), Harry (born 11.9.1932) and Renate Emmy Schulz (born 27.6.1940). The family lived in very modest circumstances, until 1940/41 in Niendorfer Straße 56/ Eppendorf (today: Geschwister-Scholl-Straße), then in the basement apartment Kegelhofstraße 14.

In 1934, Walter had been enrolled in the elementary school for boys in Erikastraße (in the section of the street that was later renamed "Schottmüllerstraße"). He did not stay here long because he had difficulties learning to read and write, so the authorities referred him to the "auxiliary school" on Opitzstraße (Winterhude). Walter now had to travel a long way to school on his own, but above all this meant that he was stamped as a pupil who needed special education. Documents in his file indicate that the Youth Welfare Office was considering sterilizing him. This did not happen infrequently with auxiliary pupils under the Nazi regime.

After graduating from the eighth year of the school (1942), Walter found a job in a car repair shop, but his wish to be allowed to do an apprenticeship as a car mechanic came to nothing: the auxiliary school certificate was not enough. After 1 ½ years in the auto repair shop, in the fall of 1943, "I got" - he writes in his CV of Feb. 7, 1944 - "the papers back because I didn't get along with my boss." He then found employment as a so-called young worker in a wholesale spice shop. Here he remained until his arrest.

Walter Schulz, he later stated in the Herford personnel questionnaire, had been registered with the "Jungvolk" of the Hitler Youth on March 14, 1938, but he had never gone to the meetings of the "Pimpfe," partly because his parents refused to buy him a uniform. It was only while he was working in the car repair shop that the HJ pressured him and his boss to such an extent that he volunteered for the fire department's Schnellkommando. He thus belonged to the HJ fire department crowd and had an easier time avoiding the other service obligations.

The so-called Schnellkommandos, which were set up in the course of the war, had the task of ensuring "the rapid and intensive fighting of stick fire bombs as they developed." In 1943, such a commando in Hamburg usually consisted of two policemen and three Hitler Youth under the age of 16. The technical equipment included heavy passenger cars with trailers, sand buckets, shovels, and bucket sprayers. The service was highly dangerous for the adolescents trained in the fast course. Many lost their lives, others were seriously injured. Walter, however, had survived his missions unharmed. On May 25, 1944, he was expelled from the HJ because of his crime.

For Walter Schulz, a time of suffering began in the juvenile prison. Whether in the carpenter's shop or the saddlery: In the eyes of his supervisors he worked too slowly, too clumsily, too reluctantly. He was obdurate and did not keep his things in due order in the cell. His observation sheets are full of these negative entries for months. It did not remain with notes. A long series of repeatedly imposed punishments is recorded: detentions of between one and four weeks, "special sport" is mentioned several times, repeated transfer to another cell.

What the sanctions actually meant in Herford in 1944/45 has not yet been ascertained beyond doubt: Herford Prison documents on this subject have not been preserved. Certainly, in those years of Nazi penal practice, confinement included solitary confinement in a cramped, bare, cold cell with water and bread, a hard cot without a mattress, yard confinement, isolation. The "special sport" probably meant drudgery. The punishments were aimed at isolating the prisoner, preventing the development of relationships, breaking his will.

For Walter Schulz, the uncertainty as to whether he would ever be released was certainly also a burden. On March 16, 1944, he tried to hang himself. This failed. The receipt was seven days of arrest. A few days later, on March 26, he tried to escape with the help of a fellow prisoner. This also failed. The punishment followed immediately: three weeks' arrest. Not recorded in the files are the - officially forbidden - beatings that the angry guards regularly administered for escape attempts.

Only at the end of 1944 are there more positive entries in the file. Perhaps this was due to a more lenient attitude of individual prison officers toward the increasingly ailing prisoner.

Günther Pehlcke, who was also imprisoned in Herford, got along better. He behaved as he wished there, did not incur any additional sanctions and, after serving his minimum sentence of one year to the day, was released on October 4, 1944 - and drafted into the Luftwaffe.

Walter's minimum sentence of one year and three months would have expired - as mentioned - on 4.1.1945. Nevertheless, he was not released, because on December 30, 1944, the Hamburg/Eppendorf State Youth Welfare Office informed the prison: "W. Sch.'s primitiveness does not allow him to be considered from a higher point of view. He must therefore remain in the penal system longer so that he does not fail again on the outside. A release is therefore out of the question for the time being."

On April 2, 1945, U.S. troops entered Herford. A detachment briefly reviewed the prisoners' requests for release and approved some. Walter was not released, although he had not had a fair trial and had already served the minimum sentence. The reason given was that it had been a brawl among youths. Thus the verdict of the Nazi Special Court was de facto recognized as legal.

On April 4, 1945, Walter and three fellow inmates attempted to escape while working in the fields at an outpost of the prison, just as an American military convoy was passing by and the opportunity seemed favorable to them. But the four were caught up by the guards and brought back to Herford. Ten days of arrest were recorded as punishment.

On admission to Herford on February 7, 1944, Walter weighed 63 kilograms (kg) at a height of 178 cm. (The medical report states that his target weight was 68 kg.) On May 25 he weighed 60 kg, on October 8 he weighed 58 kg, and on February 11, 1945 he weighed 56.5 kg.

Since the beginning of May 1945 Walter complained of increasing stomach pains. On May 9 - one day after Germany's surrender - he was transferred to the Catholic Hospital in Herford because of "stomach catarrh" (gastritis). There he died the next day, May 10, 1945, at the age of 17 years and four months, according to the hospital's notice to the prison of "influenza with gastrointestinal involvement and cardiac insufficiency." A scarlet fever in childhood was considered possible as a more distant cause.

An autopsy to determine the cause of death did not take place. Walter Schulz was buried in the cemetery "Zum ewigen Frieden" in Herford.

The prisoner's book shows that Walter Schulz received private mail only once during his 16-month imprisonment in Herford, from a friend in Eppendorf. And: He received only one visit: On June 8, 1944, after four months of imprisonment, he saw his mother for a good hour under the eyes of a guard. There were no further visits, despite several attempts on her part, which - she later said - had failed due to the increasing chaos of the war in 1944 and the disrupted train connections.

Translation Beate Meyer

Stand: February 2023

© Johannes Grossmann

Landesarchiv Ostwestfalen-Lippe, OWL_ D22_ Herford_ Nr.4725 (Schulz, Walter), darin auch das Urteil des Hanseatischen Sondergerichts plus Begründung (11 Js P. Sond. 411/43 (38c) Sond. Ger. 253/43); ebd. OWL_D22_Herford_Nr.4711 (Pehlcke, Günther); StaH 351-11_18225 (Schulz, Martha Auguste); StaH 351-11_18224 (Schulz, Richard Otto); StaH 351-11_48107 (Pehlcke, Günther); StaH 351-11_48346 (Soost, Karl-Heinz); StaH 351-11_48934 (Kraatz, Hans-Heinrich Karl); Archiv Gedenkstätte KZ Neuengamme, Aktenbestand des Komitees ehemaliger politischer Gefangener" (VVN-BdA, Landesvereinigung Hamburg); StaH332-5_9570 (Heiratsurkunde Schulz, Richard Otto); Klönne, Arthur: Jugend im "Dritten Reich"/ Die Hitlerjugend und ihre Gegner, Köln 2020; Matthias von Hellfeld/Arno Klönne: Die betrogene Generation/Jugend im Faschismus, Frankfurt/Main 1987; Kater, Michael H.: Hitler-Jugend, Darmstadt 2005; Böge, Volker: Jugendliches Aufbegehren im Krieg – die Eimsbütteler "Pfennigbande", in: Ulrike Jureit/Beate Meyer (Hrsg.): Verletzungen. Lebensgeschichtliche Verarbeitung von Kriegserfahrungen, Hamburg 1995; Diercks, Herbert: Wege Hamburger Jugendlicher in den Widerstand 1933 bis 1945, in: Zwischen Verfolgung und "Volksgemeinschaft"/Kindheit und Jugend im Nationalsozialismus, Beiträge zur Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung, Heft 01/ 2020, Göttingen 2020; Knaack, Kirsten: Die Hilfsschule im Nationalsozialismus, Examensarbeit im Fach Lernbehindertenpädagogik, Universität Hamburg, Juli 2001; Bozyakali, Can: Das Sondergericht am Hanseatischen Oberlandesgericht, Frankfurt 2005; Wachsmann, Nikolaus: Gefangen unter Hitler/Justizterror und Strafvollzug im NS-Staat, München 2004; Brunswig, Hans: Feuersturm über Hamburg/Die Luftangriffe auf Hamburg, Hamburg 1985; Jahnel/Waldmann: 125 Jahre JVA Herford, Herford 2008.