Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

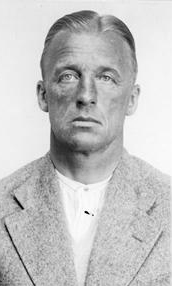

Asbjørn Halvorsen * 1898

Hallerplatz 12 (Eimsbüttel, Rotherbaum)

HIER WOHNTE

ASBJØRN HALVORSEN

JG. 1898

RÜCKKEHR 1933 NORWEGEN

IM WIDERSTAND

VERHAFTET 5.8.1942

SS-POLIZEILAGER GRINI

DEPORTIERT 1943

NATZWEILER

BEFREIT 5.4.1945

SCHWEDISCHES ROTES KREUZ

Asbjørn Halvorsen, born on 3 Dec. 1898 in Sarpsborg/Norway, imprisoned as a resistance fighter, died on 16 Jan. 1955 as a result of concentration camp imprisonment

Hallerplatz 12

Asbjørn Halvorsen was born on 3 Dec. 1898 in the up-and-coming industrial and port town of Sarpsborg, east of the Oslo Fjord, as the fifth of seven children of the self-employed master baker Christian Halvorsen and his wife Jacobine Dorthea. Like his older brother Mathæus, Asbjørn soon spent much of his free time on the soccer field. His talent was so exceptional that he was already playing in a few games in 1914 in the premier team of Sarpsborg FK and the following year – in the middle of his final exams at Mittelschule (approx. equivalent to junior high school) – he was appointed to the permanent squad at the age of only 16.

As a "center back,” he was the playmaker of his team in the game system of the time and quickly grew to be one of their outstanding players. In 1918, his performance was partly responsible for winning the first Norwegian championship for his club. In the same year, he was called up to the national team and became one of the protagonists of the first "Golden Age” of Norwegian football, during which not only the first victory finally occurred after ten years of national team history, but in 1920 in Antwerp, the Norwegian team inflicted the first defeat on the British Olympic team in its history, a team that had won all the major Olympic tournaments up to that point. By 1923, Halvorsen had played in 19 international games for his home country.

In fall of 1921, Asbjørn Halvorsen turned his back on his Norwegian homeland. With his good knowledge of German, which he had already acquired during his school days, and the commercial high school diploma he had obtained in the meantime, he wanted to further his education in the shipping industry at the Hamburg Sloman shipping company. He did not initially have any soccer ambitions, but was soon discovered for the Hamburg soccer team HSV and joined its premier league team in the same year. As a playmaker, he quickly became, alongside center forward Otto Harder – later the concentration camp guard in Neuengamme and camp commander of the Hannover Ahlem subcamp – an outstanding player and a real character who impressed with his sporting spirit, fairness, and camaraderie. Asbjørn Halvorsen played a significant role in the HSV winning the German championships in 1923 and 1928. After Harder left the club in 1931, Halvorsen was appointed team captain and in the spring of 1933, he took over the coaching duties as well.

Members and friends of the club helped him secure an adequate livelihood by giving him a share in an international freight shipping company, which was given the name Halvorsen & Koch GmbH. It maintained its office first at Enckeplatz 4 in Hamburg-Neustadt, later at Grosse Reichenstrasse 79, and at Katharinenkirchhof 2. After two of the partners had already resigned in 1924, Halvorsen was finally appointed sole managing director in 1929. Initially, the private address can be identified as the residential building at Kiebitzstrasse 66 in Eilbek, which was destroyed in the nights of bombing during the Second World War and which also housed a lottery business of his business partner Hans Koch. From 1928 onward, the Hamburg directory listed him at Hallerplatz 12 on the fourth floor. From the HSV membership directory, we learn that he resided as a subtenant with the widow of a "postal councilor” (Postrat) by the name of Paplitz.

In Sept. 1933, Asbjørn Halvorsen ended his career as an active soccer player and returned to Sarpsborg because he had been offered a "life position” as the manager of the local state health insurance company. However, after the subsequent vote of the city council against him, he gave lectures on German soccer and his time in Hamburg in the winter of 1934, and the following summer, he took over the training of the Sarpsborg FK premier league team, which he led to the finals of the Norwegian championship. In addition, the Norwegian Football Federation NFF was able to enlist his services, first in an honorary capacity as a member of the selection committee for the national team and as a soccer field inspector, and then, from 1935 onward, as a paid association coach, who was responsible for the national team and, as a traveling instructor, managed the training of club coaches. In 1936, he additionally took on the management of the association as secretary of the NFF and by this time, he combined tremendous power in his hands, which quickly earned him the title of Norway’s "Soccer General,” although this military attribute was not to be added to his official title until after World War II. With his professional competence, the persuasiveness of his personality, and his ability to lead people, Asbjørn Halvorsen created a national team that, under the eyes of the "Führer,” brilliantly defeated the German team 2-0 in the quarterfinals at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and eventually won the bronze medal.

Halvorsen had not been an opponent of National Socialism until then. To be sure, in 1947, he stated in a newspaper interview that he had left Germany in 1933 because he had not been able to live under the Nazi regime, and that he had preferred to dissolve his company before being expelled from the country. Actual conflicts with those in power, however, cannot be ascertained. Even when he left the HSV, the undiminished esteem in which the Nazi sports officials held him was just as clear as his willingness to participate in the ritual shaped by the regime. Although as an honored person he did not raise his arm to the "Hitler salute” like his teammates, he did call on those present in his closing words to give a triple "Hip-Hurrah for Germany and the HSV.” Criticism of the Nazi tyranny has not been handed down, neither in his lectures the following winter nor during his participation in the 1936 Olympics.

Only when Norway became a victim of the German war machine on 9 Apr. 1940 did the fervent nationalist began to resist. After the capitulation on 10 June, he consistently rejected the demands of the occupying power to agree on an international match between the two nations, which was intended to put on a propagandistic display of a normalization of relations. In Oct. 1940, he prevented the cup final from being claimed as a Nazi propaganda event when he threatened to cancel the game.

However, in the summer, Halvorsen’s attitude was still contradictory. He decided to make use of the Nazi rulers to assert his own sports policy interests. When on 15 July, the middle-class LI sports umbrella federation and the working-class AIF sports federation concluded an agreement on unification that did not take sufficient account of the interests of the middle-class professional associations, he turned to the Reich Commissariat, the power center of the occupying forces, to warn them of the "Marxist contamination” of the sports associations and to ask them to prevent Rolf Hofmo, the chairman of AIF, who at the time had already intensively pursued a boycott of the Berlin Games, from doing any further association work.

In the following weeks, however, his attitude changed. Halvorsen and Hofmo in particular created a new basis for the association in further negotiations. As a result, a joint "interim management” of both umbrella organizations was formed in September to prepare for its implementation. However, when the occupying forces and their Norwegian collaborators dissolved the existing sports organization on 22 November and created an umbrella organization structured according to the leader principle, the interim leadership went into illegality in order to use its authority to organize resistance against the Nazification of the sports movement.

On 16 Dec. 1940, Asbjørn Halvorsen was appointed to the interim leadership and quickly proved one of the most important organizers of the refusal to engage in any kind of sporting activity, which the interim leadership had called for in order to demonstrate its unyielding insistence on a democratic structure of the sports associations. Within the sports movement, this resistance was extremely successful: Sports events were boycotted and sabotaged by spectators and athletes, top athletes refused to train, and a large number of clubs disbanded. Moreover, this was also the first significant act of civil resistance by the Norwegian population, which was to serve as a model for the "struggle of attitude” ("Haltungskampf”) during the following years, in which people from various population and professional groups and institutions – artists, students, teachers, and parents of school children, church officials, and many more – resisted cooperation with the regime and refused to comply with its demands.

In addition to organizing the sports resistance, Asbjørn Halvorsen was also involved in the publication and distribution of illegal newspapers. This activity became his undoing. On 5 Aug. 1942, he was arrested in his apartment and severely tortured in Gestapo interrogations lasting several nights. Although he had not betrayed any of his comrades in the Resistance, after three nights – possibly following an intervention by the Reich Commissariat in favor of the soccer player who was still popular in Germany – his tormentors let up on the man who had already been beaten bloody all over his body and transferred him to the Grini police prison camp on the outskirts of Oslo. There he spent more than seven months in solitary confinement before young Kristian Ottosen, later to become the historian of Norwegian concentration camp prisoners, was assigned to him as a cellmate.

When Halvorsen’s tormentors were brought to justice after the war, he had to learn something devastating for him from their statements: His wife Minna had apparently denounced him to the Gestapo. Minna was from Hamburg and the widow of a close business friend of Asbjørn. In the winter of 1936, she followed him to Oslo with her son Felix Achim. When they married in June 1936, she also received Norwegian citizenship. The marriage, however, did not go well, and in the spring of 1942, the couple initiated divorce proceedings, which were completed in Jan. 1943, during Asbjørn’s imprisonment in Grini, apparently by mutual consent. Although Minna was acquitted of the very serious charge of denouncing her husband in Mar. 1946, and although the Gestapo lackeys may not have testified truthfully in order to shift moral responsibility for their actions or to protect their true source, there was never again reconciliation between the former spouses. While Asbjørn married a second time in Dec. 1951, Minna remained isolated in Oslo for the rest of her life, earning her living by working hard in the kitchen of the nursing home of the Catholic St. Elizabeth Sisters.

On 29 July 1943, Asbjørn Halvorsen was deported from Norway as a so-called NN prisoner, probably on the personal order of the Oslo Gestapo chief Reinhard. A Führer’s directive dated 7 Dec. 1941 had stipulated that in the case of "crimes against the Reich or the occupying power” which could not be punished directly with the death penalty, relatives and the public were to be kept in the dark about the fate of the delinquents. For the purpose of deterrence, they were to disappear without a trace into "night and fog” ("Nacht und Nebel” – NN). The most important reception camp for Norwegian NN prisoners was the Natzweiler concentration camp, which had been erected at an altitude of more than 700 meters on a ridge in the Vosges Mountains after the Wehrmacht victory over France.

Asbjørn Halvorsen reached the camp together with 33 fellow prisoners on 6 August. When he was admitted, he could not give any professional qualifications that would have made him suitable for a work assignment easier on his physical strength. The verdict on his prisoner’s card "deployment as unskilled laborer” meant that he was assigned to work in the quarry where the red granite for the megalomaniacal buildings of the future "Reich capital Germania” was to be extracted. It was one of the deadliest work detachments in the camp, for in this area, the prisoners were exposed to particularly rapid depletion of their strength through the heaviest labor. Although he received covert benefits for several weeks from one of the Kapos (concentration camp overseers), who had recognized his former soccer idol, it was a relief for him that in Jan. 1944, he was transferred to the work detachment in the "Bad” ("bath”) – the new crematorium barrack, which housed the incinerators and also shower rooms for the newly arrived prisoners.

However, the humidity to which he was exposed in the "Bad,” together with the cold of winter, took its toll: On 21 Mar. 1944, he was admitted to the infirmary with high fever and a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. It was not until 21 June that he was discharged with the restrictive note indicating, "Discharged for light work in the sick quarters.” Although he had thus attained a relatively protected position, he was by no means a preferential prisoner recognized by the camp administration. He was not listed in a corresponding list by Commandant Hartjenstein dating from Aug. 1944, which also contained the names of some Norwegians.

On the other hand, the soccer star, well-known in many countries, enjoyed great respect among his fellow prisoners, including important prisoner functionaries. This enabled him to build up a network of contacts through which he obtained valuable information about the world outside the barbed wire, especially about the war events, which he passed on to his Norwegian comrades in evening lectures that were always marked by an optimistic mood. This fact alone made him a very important pillar of support for the group of Norwegians in Natzweiler. He was able to help individuals in critical situations, but occasionally also personally. For example, when Trygve Bratteli, the Labor Party politician and later head of the Norwegian government in the early 1970s, was close to physical collapse because of work in the quarry, Asbjørn Halvorsen managed to get him assigned to less exhausting work.

Since the offensive of the Allied invasion forces in the summer of 1944 led to the expectation that the Natzweiler main camp on the left bank of the Rhine would soon be liberated, the evacuation order was issued by the SS leadership on 1 September. While the vast majority of the prisoners were transferred to Dachau concentration camp, Asbjørn Halvorsen remained in the Natzweiler complex with two doctors, the Norwegian Leif Poulsson and the Belgian Georges Boogaerts, as well as five other prisoners employed in the infirmary. They were assigned to the Neckarelz subcamp in North Baden on 20 September to support medical care there and in the other Neckar camps. We do not know exactly what work Asbjørn Halvorsen did in Neckarelz. According to his own account, however, he himself was a patient in the camp for more than two and a half months, as he had contracted pneumonia on both sides of the lung.

In early 1945, Halvorsen and Leif Poulsson were transferred to the Vaihingen concentration camp, 30 kilometers (some 18.5 miles) northwest of Stuttgart, where they arrived on 5 January. Georges Boogaerts followed them a few days later. Vaihingen was intended to be a "patient and recreation camp,” where the prisoners who were unfit for work within the Natzweiler complex were to be concentrated in order to make them fit for work again later. In reality, however, due to completely inadequate structural and hygienic conditions and a serious lack of basic prisoner supplies, it had become a pure death camp. Leif Poulsson, as senior prisoner doctor, and Asbjørn Halvorsen, as infirmary elder, were commissioned by the SS commandant’s office of the Natzweiler concentration camp to bring about an improvement in the conditions. They failed, however, because of the criminal structures that corrupt SS ranks and a clique of prisoner functionaries in Vaihingen had set up. Since Asbjørn Halvorsen refused to assert his authority by the use of force, he was relieved of his function by the SS camp physician soon after his arrival and demoted to the position of infirmary clerk.

The dying in the Vaihingen concentration camp reached a horrifying climax when typhus was introduced into the camp by a prisoner transport in mid-February. Almost half of all prisoners succumbed to it until liberation. Late in the day – on 20 March – the epidemic also took hold of Asbjørn Halvorsen. Surviving the febrile crisis just barely, emaciated to a weight of only 48 kilograms (about 106 lbs) and suffering severe damage to the heart. When the 16 Norwegians still alive were rescued from the inferno on the morning of 5 April by a White Bus of the Swedish Red Cross and transferred to Neuengamme concentration camp in the following two days, he was barely fit for transport.

The Red Cross physicians decided that the Vaihingen prisoners, because of their pitiful condition, would be the first prisoners to be allowed to travel on to Sweden on 9 April to recover. The only exception to this was Asbjørn Halvorsen, who was so weakened that they did not want to take responsibility for his transport. Only on 12 April did they dare to take him to Helsingborg in a White Bus. After his arrival two days later, he was first admitted to the Epidemics Hospital and after some time, transferred to the Ramlösa Sanatorium. There, he recovered noticeably and in the evening of 7 May – in the high spirits triggered by the news of the German surrender and the armistice agreed upon for the evening of the following day – he was able to leave for Stockholm, where he was to remain a guest of the Swedish Soccer Association until his complete recovery. However, his impatience finally to see his homeland again in freedom after almost three long years was so great that, contrary to all medical advice, he set off on his journey home to Oslo on the morning of 30 May, where at noon he was greeted joyfully by a small group of friends at Oslo East Station.

It was also the desire to get back to work at last for soccer that drove Asbjørn Halvorsen home so early. Important tasks awaited him: The soccer infrastructure destroyed during the occupation had to be rebuilt; the Nazi sports association had to be liquidated; and the democratic union of umbrella federations, which had begun in 1940, had to be completed. In addition, thousands of soccer players craved to compete in sports again after the years of the sports boycott. Thus, Halvorsen organized a "Liberation Cup” in the summer, to which spectators, too, flocked in unprecedented numbers. The first international matches against the Scandinavian neighbors showed, however, that Norwegian football was down in terms of performance after the years of self-imposed passivity, so that additional measures had to be taken to raise its level again. In addition to these tasks, Halvorsen also took over the office of General Secretary for the interim management of the umbrella associations for a transitional period in the summer.

In June 1945, Asbjørn Halvorsen joined the founding manifesto of the "Norwegian-Soviet Russian Connection” (Norsk-Sovjetrussisk Samband), which, in gratitude for the war effort of the Red Army, which had also liberated parts of the Norwegian Finnmark in the fall of 1944, was committed to strengthening friendship and cultural exchange between the two peoples. Already in the negotiations with Rolf Hofmo and the cooperation with the representatives of the AIF during the illegal interim leadership of the umbrella organizations, the parties had built up mutual trust and respect for the differing convictions of the others, especially since they were united by this time in the pursuit of the restoration of democracy and the rule of law in a free Norway. Finally, during the struggle for survival in the camp, Asbjørn Halvorsen also felt that every ideological dispute had lost its justification. He was thus able to get the Socialist Trygve Bratteli to give a series of lectures in Vaihingen to Norwegian prisoners on the future of the country after the war, so that by looking ahead to the near future of regained freedom, the remaining will to live could be mobilized. A personal friendship that lasted throughout the period of captivity was forged by Asbjørn Halvorsen and the Communist Léon Thurm, a member of the board of the Luxembourg Soccer Association, who was imprisoned in Natzweiler with two other colleagues from the Association’s management. The hope was that the first international match between the two nations would finally be organized after the war. When FIFA’s first post-war congress met in Luxembourg in July 1946, the opportunity had come. The match – "born in suffering, launched in exuberant joy” – was not only a worthy conclusion to the congress, but also a very personal "celebration of joy in rediscovered freedom” for the camp comrades.

The post-war period in Norway was characterized by a will for "great reconciliation” between the middle class and the workers’ movement, which went beyond an indeterminate feeling of national unity. The resistance fighters on the home front and those returning home from captivity, exile, and wartime deployment were united by the idea that they had not "fought shoulder to shoulder” to return to pre-war conditions, "to unrestrained free competition, to crises and social hardship.” A new national consensus emerged under the leadership of the Labor Party: "The vision was a united people and a better society – the new welfare state.” Asbjørn Halvorsen implemented its basic ideas of solidarity, justice, and economic security in the "Soccer Society” in a league form that increased the permeability between the playing classes and, with its levy system, drew the rich traditional clubs a far more into financing the small clubs. Its enforcement against all partial interests, which opposed the spirit of the times, was considered by many of his contemporaries to be his greatest work for the future of Norwegian soccer.

In the years after the World War, Asbjørn Halvorsen took on a number of other tasks for the Soccer Association. As a member of the management team, he was involved in the foundation and development of a state-run soccer pool society, which was to secure a considerable amount of funding for Norwegian sports, and he was delegated to the Norwegian Olympic Committee by the NFF. In Sept. 1951, he used his personal authority as a former concentration camp prisoner to successfully campaign against fierce resistance for the invitation of West German athletes to the Winter Olympics, to be held in Oslo the following February. He wanted a new beginning in the interest of young people that were no longer responsible for the horrors of Nazi rule. In the same year, he spoke out in favor of an early resumption of relations between the two countries in soccer, and met with the former "Reich coach” Herberger and secretary general Xandry, leading officials of the DFB (German Football Association) with a Nazi past, to normalize the relationship.

Only much later did he resume his relations with his old friends at HSV. Perhaps he had been waiting for his former comrades to take the initiative, for him to receive a signal that revealed interest in his fate, that admit to omissions or errors. Obviously, this did not happen. In the membership of the HSV, no different spirit prevailed than among the great majority of the West German population. Instead of attempting to account for the causes, conditions, and extent of participation in the Nazi injustice and to come to terms with their own guilt, they chose the path of continued repression and denial. One felt oneself to be a victim of dictatorship and war, for which one did not bear responsibility. In this self-image of the former perpetrators and followers, there was no place for interest and compassion for the survivors of the crimes.

In 1953, however, the lot brought Norway and Germany together in the qualification for the 1954 Soccer World Cup. The return match was awarded by the DFB to the new Hamburg Volksparkstadion. Asbjørn Halvorsen would have been aware that the breach would probably have been final if this opportunity were not seized to approach each other again. He would then no longer have been able to relive the memory of the best years of his active soccer player’s life in the atmospheric exchange with those who had been there with him, at the places that rekindled the old emotions. There would have been forever a dark shadow on the pictures of the great battles and victories. Asbjørn Halvorsen meant exactly that when he confessed, "Despite everything that has happened later, I do not want to cut out of my life the Hamburg years and the matches at HSV and against the many German clubs. So he turned back to his old friends, met them again several times during the last two years of his life. In order to avert the loss of such an important part of his own life, he was prepared not to count the past against those who were unwilling to acknowledge the wrongs of that past, to forget for their sake what had happened – in a sense of the word that comes close to forgiveness.

It seems that Asbjørn Halvorsen – as well as many other former prisoners – also tried with all consistency to erase his memory of the horrors of the concentration camp, that is, to forget in that customary sense of the word. In order to be able to live on at all, he had to escape the shadow of the horror of the concentration camp, the constant inner presence of violence and death, of extreme humiliation and degradation. His descriptions and statements about living and dying in the camp appeared sober and dispassionate in the first months after the war, hardly revealing any of his feelings. In the period that followed, they became less frequent; he kept silent in front of his family and friends and refused to give any concrete information in judicial testimonies.

However, in the end it was not the mental, but the physical damage caused by the concentration camp that led to his early death. On 16 Jan. 1955, the 56-year-old was found lifeless in his hotel room in Narvik. During a business trip for the soccer association, his heart had stopped beating. With his death, football lost at an early stage a personality whose greatness extended far beyond the inner circle of the Norwegian association. In fact, he took on an exemplary significance from his credible and consistent perception of the social responsibility of sports, from his unbreakable humanity in a time of threat and destruction of all human values.

Translator: Erwin Fink

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: September 2020

© Jürgen Kowalewski

Literatur: Kowalewski, Jürgen, Asbjørn Halvorsen – Fußballstar, Widerstandskämpfer und NS-Opfer. In: Verband Odenwälder Museen e.V. (Hg.), Vergessene und verdrängte Geschichte(n). Kolloquium anlässlich des Internationalen Museumstages am 21. Mai 2017 in der Gedenkstätte Neckarelz, S.32 - 61. Osterburken 2019; Asbjørn Halvorsen. In: Die Raute unter dem Hakenkreuz (Arbeitstitel). Das Buch erscheint im Herbst 2020 im Verlag "Die Werkstatt" in Göttingen.