Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

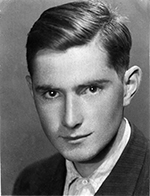

Georg Himmel * 1920

Bismarckstraße 68 (Eimsbüttel, Eimsbüttel)

HIER WOHNTE

GEORG HIMMEL

JG. 1920

AUSGEWIESEN 1938

ZBASZYN

SCHICKSAL UNBEKANNT

further stumbling stones in Bismarckstraße 68:

Max Himmel

Max Himmel, born 17 Dec. 1887 in Krukienice, deported 28 Oct. 1938 to Zbaszyn, returned, arrested several times, killed in Dachau concentration camp on 13 Feb.1941

Georg Himmel, born 19 Nov. 1920 in Hamburg, deported 28. Oct. 1938 to Zbaszyn, missing

Bismarckstraße 68

Max Himmel was born in Galicia near Lemberg. He was a tailor. He had already seen much of the world when he married Johanna Emma Emilie Pfeffer from Hamburg in the spring of 1918. She was lovingly called Hanni by her family, was of Protestant confession, and not of Jewish heritage. Max Himmel was adventuresome and fond of traveling. He and his young wife mounted his motorcycle and rode off to explore the world. Their first son Arnold’s birth (born 20 Aug. 1918) did not take place in Hamburg like those of his younger siblings Georg and Klara Dorothea (born 20 Sept. 1936). Arnold was born in Norway.

At the end of Jan. 1920, Max Himmel had registered as a tailor at the Chamber of Crafts in Hamburg, giving his address in Eppendorf as Nissenstraße 9 I. He called his business "Viennese Tailor for Ladies and Gentlemen" (Wiener Damen- und Herrenschneiderei) – as a play on his apprenticeship time in Austria. During the period of hyper-inflation, he worked as hired labor, as he also did in 1924. In the mid 1920s, he started his own business in a basement shop at Bismarckstraße 68, however the business did not flourish. From 1932 to 1934 Max Himmel had to draw on welfare support now and again. In the mid 1930s, the family moved to Hoheluftchaussee 14, into a four-room apartment on the ground floor, left side. The monthly rent was 60.58 Reichmarks in 1938.

Within the framework of the "Poland Operation" (Polenaktion), the family, meaning Max and Johanna Himmel and their two under-aged children Georg and Klara Dora, were deported to Zbaszyn/Neu-Bentschen on 28 Oct. 1938. The police sealed off the rooms at Hoheluftchaussee. According to official provision, once property was sealed off, the local police authority would apply to the guardianship court to have an absentee conservator appointed to attend to property matters. Inventory was taken of the property, and existing business was wound up. The representative for Max Himmel was the Jewish "legal advisor" Siegfried Urias, who, in turn, issued a substitute power of attorney to Johann Georg Pfeffer, Max Himmel’s father-in-law. In Nov./Dec. household items were sold, and clothing finished in the tailor’s shop was returned to the customers. The proceedings were used to pay for gas, electricity and rent. Some items, such as razor blades, shoe laces and a harmonica were sent from Hamburg to Max Himmel in Poland. The income from the sales exceeded the expenses by a small amount. Max Himmel gifted the money to his parents-in-law.

The Himmel couple returned to Hamburg mid 1939 with their small daughter. At that time the apartment at Hoheluftchaussee was already rented out to someone else. Nothing was left of their household belongings, nor were they able to discover their whereabouts. The Himmels were taken in by Johanna Pfeffer’s parents at Neustädterstraße 20. Max Himmel endeavored to line up a departure for Poland. He applied to move with the necessary items for daily life. His application was approved in Aug. 1939. Yet a short time later, after war had broken out, Max Himmel was arrested – like thousands of other "Polish" Jews who were still in Germany – and detained in Fuhlsbüttel. He suffered from heart disease and spent some time at the military hospital in Feb./Mar. 1940. From Fuhlsbüttel he was sent to the concentration camp Sachsenhausen at the beginning of 1940, and in Aug. 1940 he was transported to concentration camp Dachau where he died. The urn with his ashes was interred at the Jewish Cemetery in Ohlsdorf an der Ilandkoppel, where his wife, son Arnold and his wife were later buried.

Their son Georg is missing. In Mar. 1936, Georg began an apprenticeship as a precision mechanic in Hamburg at the company Gustav Fischer, Schönstraße 8 (at the time St. Pauli). He lived at Sternstraße 107 in the basement and presumably had to break off his apprenticeship due to persecution and then went to Hachschara at the Brüderhof. Unlike his brother Arnold, Georg was a Zionist and wanted to immigrate to Palestine. At the Brüderhof north of Hamburg, he prepared for emigration. The youth organization Hechaluz maintained an agricultural training center there for a time. The Brüderhof belonged to Rauhen Haus. The tenant received a monthly subsidy from the Reich Association of German Jews. Up to fifty Jewish youth were to be trained in farming at the Brüderhof. It is not know whether he was taken directly from the Brüderhof to Poland. There are indications that the "Chaluzim" from the Brüderhof were able to take the train back to Hamburg after three days in Zbaszyn, but Georg did not return to Hamburg. After being deported to the Zbaszyn camp at the Polish border, the camp was shut down, and he stayed in Poland following an unsuccessful attempt to return to Hamburg. In 1942 he probably reached Lemberg in Galicia where he worked for six months at a branch of Metrawatt AG Nürnberg as an ethnic-German skilled laborer for the military. One day there he was arrested on the open street, as noted in a Metrawatt AG letter to his mother dated 16 Feb. 1943. His subsequent fate is unknown. His mother evidently worked in vain for his release. A reply letter still exists from the district captain (Kreishauptmann) in Brzezany, Office for the General Public and Care (Bevölkerungswesen und Fürsorge), German administered part of Poland (Generalgouvernement Distrikt Galizien), dated 11 June 1942: "In response to your correspondence dated 4 June1942, concerning the return of your son to Hamburg, I inform you that the rejection was not issued here. I have forwarded your letter to the office responsible for the rejection, requesting further decision." At the beginning of Jan. 1943, a colleague from Lemburg asked his mother for information. He had last seen Georg before the Christmas holidays in 1942 and was surprised that he had left behind money and belongings.

Karin Guth reported on their son Arnold in her book "Bornstraße 22". In Hamburg he had fallen in love with Lieselotte Geistlich, a "half-Jewess", who had to move into the "Jew house" on Bornstraße with her parents and siblings and was deported to Theresienstadt on 10 Mar. 1943. Lieselotte survived the end of the war, returning to Hamburg in June 1945. Arnold Himmel and she married on 8 Dec. 1945 and lived together until Arnold’s death in 1980. They had no children.

Like Arnold, his mother Johanna and his sister Klara Dorothea survived. Following the arrest of her husband in Hamburg, Johanna was conscripted for war service and worked as an anti-aircraft gun assistant at Großneumarkt. After the war ended, she again had to apply for German citizenship, for Max Himmel, his wife and his sons were declared stateless under National Socialism. Klara married and had two sons. In 1989 she took her own life.

Translator: Suzanne von Engelhardt

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: October 2016

© Susanne Lohmeyer, Susanne Rosendahl

Quellen: 1; 2 (FVg 8469); 5; 8; StaH 213-8, 451 a E 1, 1 d und 451 a E 1, 1 e; StaH 332-5 Standesämter, 2334 + 952/1894; StaH 351-11, EG 171287 und 191120 Georg Himmel; StaH 621-1/86 Familienarchiv Siegfried Urias, Sig. 20; Bornstraße 22. Ein Erinnerungsbuch von Karin Guth, Hamburg 2001, S. 25ff.; www.jfhh.org/suche.php; Gespräch mit Ursula Geistlich am 21.12.2011; Peter Offenborn, S. 351ff.; Auskunft von Robert Parzer, Archiv und Museum Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen; Sieghard Bußenius, Ausbildungsstätte, www.schoah.org/Schoah/bruederhof.