Search for Names, Places and Biographies

Already layed Stumbling Stones

Suche

Dr. Erich Brill * 1895

Brahmsallee 47 (vor der Wiese) (Eimsbüttel, Harvestehude)

Inhaftiert 1937 - 1941 KZ Fuhlsbüttel

Deportiert 1941 Riga

Ermordet 26.03.1942

Dr. Erich Brill, born 9/20/1895 in Lübeck, detained 1937, deported to Riga on 12/6/1941, murdered there on 3/26/1942

Brahmsallee 47

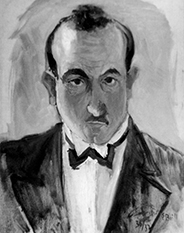

The name and the oeuvre of the painter Erich Brill today are all but forgotten. Everything we know about him today we owe to the intensive research of the art historian Maike Bruhns, who devoted her work to tracing the art denounced as "degenerate” by the Nazis.

Erich Brill’s father, the timber merchant Wolf Brill, came from Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia), his mother Sophie, née Morgenstern, was a native of Romania. From Lübeck, where the couple’s eldest son Wolf was born in 1895, the family moved to Hamburg, where they took residence at Brahmsallee 47. Together with his brother Gustav, Wolf Brill established a timber wholesale business in the Hamburg Freeport, which flourished until World War I.

Erich and his three younger siblings Fritz, Irma and Otto grew up in wealthy circumstances. After completing highschool at the Wilhelm Gymnasium and the Heinrich Hertz Gymnasium, he absolved a commercial apprenticeship on his father’s company. On account of his frail health, he was exempt from front duty at the beginning of World War I in 1914. According to his own account, he served in Hamburg with the Reserve Infantry Regiment 76. Erich’s penchant was for the arts, but his father insisted that he learn a profession that would assure his subsistence. Erich studied national economics and philosophy at the University of Frankfurt, finishing with a Ph.D. in 1919; the same year, the Brill Brothers’ timber business went bankrupt due to the consequences of the war. Alongside of his studies, he took art courses. Richard Luksch, Professor at the Lerchenfeld school of arts and crafts in Hamburg from 1907 to 1936, had the greatest formative influence on him. A talented painter, Erich Brill caught the attention of prominent representatives of the German art scene. Old Max Liebermann encouraged him, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff became his sponsor, and he was a friend of Gustav Pauly, the director of the Kunsthalle, Hamburg’s Museum of Art.

In 1920, Erich Brill rented a studio in Lübecker Strasse and, as a freelance artist, began to organize exhibitions. The 25-year-old’s courage and success impressed the journalist Martha (Marte) Leiser, a year older than Erich. She had studied in Heidelberg and received a Ph.D. for her dissertation on female workers in the Indian cotton industry. In Hamburg, she worked at the World Economics Archive and wrote for the daily Hamburger Fremdenblatt and other newspapers as well as for the tourist magazine of the Hamburg South American shipping line, enjoying universal respect. Martha Leiser and Erich Brill married on September 28, 1920; their daughter Alice was born on December 20 of the same year. The couple was divorced on October 21, 1921. Erich Brill did not want to commit himself, rather remain free to develop as an artist, travel and gain impressions. But he and Martha remained joined in friendship. Erich Brill was well linked to the Hamburg art scene, joined the artists‘ association Hamburger Künstlerverein and took study trips to Italy, Egypt and Palestine. The oriental atmosphere attracted him. In Jerusalem, he painted Jewish motifs; in Paris, he attended courses at the Académie Colarossi, who stood in deliberate opposition to the dominant conservative attitude of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Open to all innovations, he refused to belong to any established school. His paintings, initially impressionist, became more and more expressionistic. He often worked outdoors, seeking new ways to capture "the translucent endless color of the landscape.” But then, his curiosity in human beings produced a lot of portrait studies. In 1926, he had to undergo a cure for a tuberculous eye disease in Davos, Switzerland. As he was not allowed to paint during that time, he made cloth character dolls with considerable success. Later, he spent some time in the Ascona artists’ colony, characterized by its peace activist mindset and a holistic philosophy. The colonists lived a naturist life with vegetarian food and practiced nudism. The group’s pilgrimage site was Monte Verità, the "Mountain of Truth” above the town. In Locarno, Brill gave painting and drawing lessons, in Positano on the Italian coast, he lived on and off with his ex-wife Martha Brill and their daughter Alice.

After the death of his father, Erich Brill returned to Hamburg in 1927 to be near his mother. Here, the Jewish Community appointed him to artistically redesign the New Dammtor Synagogue. In its religious orientation, Brill’s new Orientalizing style of the central place of worship was a compromise between strict orthodoxy and modern liberalism. Erich Brill was a member of the German-Israelitic Community, but did not feel religiously committed. As an artist, he was conscious of his Jewish roots, a fact that is evident in his essays published in the Isrealitisches Familienblatt ("Israelitic Family Paper”) and other Jewish media. Concurrently, he was editor of the Allgemeine Künstlerzeitung ("General Artists’ Paper”). Up to 1933, 25 exhibitions of his work in Hamburg, Berlin, Munich and Jerusalem achieved varying, sometimes amazing success. In 1929, he applied to the government of Hamburg for support for an artistic journey, referring to numerous positive reviews of his paintings in Berlin and Hamburg dailies. In her autobiographic novel Der Schmelztiegel ("The Melting Pot”), Martha Brill wrote: "He knew all European capitals, the dance floors of the ballrooms and the pavement of the streets. Everywhere, he had been celebrated, regaled, adored; wherever he went, he had been given easy victories. He was sure of his success.”

From 1931 on, however, sneering comments on his "Jews’ art” increased in number. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, his work was classified as "degenerate.” His portrait of the painter Hermann Struck was perforated, his picture of Albert Einstein destroyed, his portrait of Hamburg’s Chief Rabbi Joseph Carlebach disappeared. From the increasingly anti-Semitic atmosphere in Germany, Erich Brill fled to Amsterdam, where his brother Fritz lived and the art dealer Peter de Boer organized exhibitions and sales of Brill’s paintings.

In 1933, his divorced wife Martha Brill immediately lost her job and thus her subsistence in Hamburg. With her daughter Alice, she spent some time in Mallorca and then unsuccessfully tried to find work in Florence and Rome. In an attempt to start afresh in Brazil, she brought Alice to her father in Amsterdam and set out for Rio alone. In her novel Der Schmelztiegel, Martha Brill describes the difficulties of a single woman to gain a foothold in a foreign country with an unfamiliar language. Finally, she found a job with a refugee organization that suited her social philosophy and enabled her to ask her former husband to bring Alice to Brazil. In August 1934, Erich and Alice Brill arrived in the "dream town” of Rio de Janeiro. Erich was fascinated by the country’s tropical landscape; for some time, he lived and painted on the small island of Paquetá near Rio. And he also introduced Alice to painting. Later, his daughter recalled how he had admonished her to always live and paint naturally and in harmony with nature. Then, Erich Brill moved to Sao Paulo, where he made a name for himself in the art scene and was able to do several exhibitions. In Der Schmelztiegel, Martha Brill wrote: "Receptions, cocktail parties, rave reviews – a one-day fame. Not a single picture was sold. The Germans didn’t buy because he was a Jew, and the Jews didn’t buy because the exhibition was held at a German club. From what should the painter live?” Considering the shattering news from Germany, Brill’s conditions of living in Brazil were comparatively favorable, but his restless spirit drove him away. He was immensely homesick for Europe and Germany, his daughter Alice recalled.

In spite of all warnings, Brill in March 1936 first travelled to Amsterdam, where he exhibited his new paintings of South American motifs. Again, Peter de Boer helped him make good sales. Then, Brill wanted to go to Hamburg to dissolve his large studio on Jungfernstieg and to Berlin to collect some outstanding money. His brother Fritz implored him not to set foot in Germany. Nonetheless, Erich Brill went to Hamburg in November 1936. According to Martha Brill and people who knew him well, he believed in the good in man, was politically naïve and followed his sentiments and desires.

It is unknown who denounced him for "racial defilement”; on February 1, 1937, Erich Brill was arrested in Berlin and taken to the Charlottenburg remand prison in Kantstrasse 79. His closest relative, his mother, widow Brill in Hamburg, Brahmsallee 47, was informed. On request from the chief prosecutor, Erich Brill was transferred to the Hamburg remand jail at Holstenglacis 3 on February 16, where he waited 14 months for his trial. By studying court records, he made himself familiar with judicial and court procedures, of which he had no idea. He wrote his mother about novels he was reading and sent her examples of animal poems he had written in the style of Christian Morgenstern, which he planned to publish under the title Tiersalat ("animal salad”) after his release. An example from the poem Krokodilstränen ("Crocodile Tears”) shows how he attempted to cope with his situation with gallows humor:

Ein Krokodil lag wie ein Vorweltdrache / Am heissen Ufer nah dem Weissen Nil, / Sann unbeweglich stundenlang auf Rache / Mit grünen Augen starrend auf ein Ziel. / Im Schlamm begann es dann nervös zu wühlen / um sich des Kummers wegen abzukühlen. ("Like a prehistoric dragon, a crocodile lay motionless / on the hot bank of the White Nile,/ pondering revenge for hours on end / staring at a goal with green eyes. / In the mud then, it began to nuzzle nervously / to cool off a bit because of its grief.”) The isolation affected the sociable painter. To his mother, he wrote: "Ten years ago, I wanted to enter a friary, but for me, living in a cell is not an ideal condition, even with ultimate mental concentration.” In April 1938, his verdict was finally in sight. Erich advised his mother not to think about him too much. "I’ll manage to pick myself up again when all this is over. It must be over once.”

Brill bitterly complained that he did not receive sufficient support by an attorney before interrogations and confrontations and that Manfred Heckscher, the Jewish attorney assigned to him, had lastly done him more damage than good by his harsh and suggestive manner. At the trial, defense counsel Heckscher spoke of the "unfortunate race laws”, an utterance for which he had to apologize immediately, calling it a slip of the tongue.

Half a year later, Heckscher himself was accused of racial defilement and succumbed in an extremely difficult trial.

On May 5, 1938 the verdict in the penal case of Erich Brill was pronounced. He was sentenced to four years at hard labor with only 5 months of remand considered "for crimes pursuant to Arts. 2, 5 paragraph 2 of the Law for the Protection of the German Blood and the German Honor and for a violation pursuant to Art 218, 49 of the Penal Code (assistance to abortion). The penalty was unexpectedly severe. The date for his release was set at December 10, 1941 at 12:30. Three days after his sentencing, Brill wrote to his mother: "Not in my most pessimistic appraisal had I considered it possible that the gods would turn against me to such an extent and that fatal mistakes I made in my abnormal condition would carry such weight.”

The "fatal mistakes” had been his own inability to realistically appraise his situation. The convict later resumed. His defense counsel had not prevented him from lowering his guard against the Nazi justice officials and entangling himself in contradictions. The court did not consider Brill’s version of the events credible. It read thus: In 1932, he had met the "Aryan” art enthusiast Gertrud Jarick and made friends with her. She accompanied him on trips and showed great interest in his work. It is possible that Brill gave rise to her hopes of a marriage. But she was not the only woman who found the painter attractive. Other ladies were also interested in the artist and his work. When he returned from Brazil in 1936, his friend Gertrud Jarick visited him at the Hamburg boarding house in the street called Schulterblatt where he was staying; from there, the two went to the island of Helgoland for a weekend. The young lady now seemed to seriously want to commit Brill to her and imagined going to Brazil with him, where the union of an "Aryan” with a Jew was not threatened by punishment. Brill, however, wanted to end the liaison.

In the late summer of 1936, Gertrud Jarick became pregnant. Brill reacted annoyed when she followed him to Berlin, where he wanted to tend to some business and pay another former girlfriend, "Fräulein Schiele” a commission for having arranged a sale of a picture. It turned out that Fräulein Schiele was well acquainted with a doctor willing to "help” women with unwanted pregnancies. Another friend, also pregnant, joined them. Brill stayed clear of these "female affairs” and let the women handle the matter on their own. Only when Fräulein Schiele asked Brill to pick up Gertrud Jarick from the practice of the doctor who had performed the "removal” did he prove helpful, and cared for his girlfriend for another five days. When accused of "accessory to abortion” after extensive and contradictory testimony, Brill considered this a gross injustice and himself innocent of this charge. However, he was found guilty, and further 18 months were added to his sentence for "racial defilement”

On May 12, 1938, Erich Brill was admitted to Fuhlsbüttel Prison in Hamburg, but transferred to the penitentiary in Bremen-Oslebshausen ten days later, where his contacts to the outside world were severely restricted. He was not allowed to correspond with Gertrud Jarick at all, and with his relatives and counsels only at fixed intervals. Visits were only permitted even more rarely. It seems that the jailors wanted to prohibit everything that might have eased the prisoner’s detention conditions.

Brill now concentrated on a revision of his verdict, hoping for a reduction of his sentence. He collected all evidence that might exonerate him. With the help of his sister, he supplied proof that three of his grandparents were not born Jewish, he himself thus only 50 percent Jewish at the most. The court, hoover, refused to consider this, and it also ignored Brill’s reasoning that he had lived in Brazil, a multi-racial country, in 1935 when the Nuremberg race laws were passed and thus when he returned to Germany had been unaware of the fact that he had become delinquent when he entered a relationship with an "Aryan” woman.

Indeed, he was temporarily transferred to the Hamburg city remand jail from October 14 to November 5 "for interrogation”, but he was not granted mitigating circumstances. It is not documented whether the 6th criminal chamber in charge of "racial defilement” even considered Brill’s meticulously prepared argumentation. The court refused to reconsider his case. An appeal for clemency Sophie Brill filed with the Hamburg court of appeals on behalf of her son was turned down. In his comment, the chief prosecutor wrote that "within the scope of the powers granted me by the Reich Minister of Justice pursuant to Art. 17/1 of the clemency ordinance, I was in no position to grant a pardon in this case.”

From then on, Brill focused his hopes and efforts on emigrating. His sister Irma in the meantime had gone to the United States with her family and tried to obtain a visa for him.

In the meantime, Brill continuously suffered from the conditions of his detention. Entries in his prison record testify that he didn’t surrender without resisting. Penalties for "disturbing silence and order in his cell” or "having made chess figures without permission” and "hiding one pc. Pencil and two steel pens and working with them in his cell” are listed. The usual punishment was "one day on bread and water.” The felony " writing a poem aimed at guard sergeant Schmidt and pasting it on a piece of cardboard” was sanctioned with "four days on bread and water.”

The prisoner’s health was continuously monitored, especially regarding if and when he was "fit for the moor”, i.e. if he could be detailed to outdoor work, i.e. digging peat. Brill himself asked to be employed in the workshop on account of his frail body. He was indeed underweight, but otherwise only suffered from an occasional sore throat, and once from furunculosis. On account of his increasingly feeble eyesight, he applied for a pair of glasses. He did not complain about the food.

The communication ban tormented him more than the material deprivations. Sophie Brill was not allowed to speak with her son before she left for the Netherlands in 1939, but she was permitted to deposit a suitcase with his belongings with the prison management that was to be handed over to him on his release.

In January 1940, Erich Brill was transferred to the Celle penitentiary, in August of that year to the prison in Hamelin. Brill still believed he could return to Brazil or emigrate to some other country. A letter from the warden of Celle prison dated February 1, 1940, reads: "For reasons of fairness to all other Jewish inmates who intend to emigrate, I am unable to grant [you] such a privilege.” The "Consulent” Scharlach pleaded for Brill, but was not allowed to visit him; instead, he had to handle everything by correspondence.

On September 13, 1940, now in Hamelin Prison, "re: Preparation for Emigration”, he requested all relevant documents to be handed over to him. And was told that he had another year’s time, and to get back a year later. And duly, in September 1941, Brill requested the issuing of an ID card, the opportunity to get passport photos and a medical certificate. As now he had a visa for Cuba, which his sister had got for him in the USA for 500 dollars. On October 20, 1941, the prison physician Dr. Brandt issued the certificate that stated: "The prison inmate Erich Brill is fit to work and to be transported, and free from contagious diseases. He can be deployed to all types of agricultural work.”

On November 22, 1941, one week before the end of his sentence, Erich Brill was transferred to the Fuhlsbüttel Police Prison for the 23. Criminal division and released on November 29, 1941. He was "free” – for deportation.

Temporarily, he moved into the Nordheimstift, an old folks’ home belonging to the Jewish Community. On a postcard to his mother in Amsterdam, he wrote: " My dearest, beloved Mum, I am free since noon today! Rejoice with me, even if it is too late to fulfill our old plans! Unfortunately, the wonderful, precious visa for Cuba is of no use … I have tried everything … if there is no escape, we will just have to be brave, my dear little Mum. It is no use to fight against your fate, even if it is grim.” Brill’s last letters from Hamburg all circled around his deportation. It was scheduled for December 4, 1941, with destination Minsk, but was delayed on account of railway technical problems. Brill used the reprieve to visit old friends. At Brahmsallee 47, he received a hearty welcome from the new owners – in this case, the "aryanizers” were good friends of the previous Jewish owners. A lady friend of the Brill family was surprised when Erich suddenly stood before her. In a hasty letter, he wrote: "Imagine, my dear little Mum, whom I met here, and with whom I am having a splendid conversation about past and future times?” – "me, Ilse Karlsberg”, the friend continued, " we want to make these days as pleasant and nice for him as it’s possible under these circumstances”, she asserted.

– Brill also called on Herr Bauer, another old friend: "If I only had time to go there again, where I can sit in beautiful, tastefully decorated rooms under my pictures.” – the Carlebachs, too, were delighted about Brill’s visit. Chief Rabbi Joseph Carlebach had visited Brill in prison as official spiritual counsel, and Brill had given him a small figure kneaded from bits of bread and blackened with shoe polish. In her book Jedes Kind ist mein Einziges ("Each of my Children is my Only Child”), Miriam Gillis-Carlebach recalled: "With diabolic deliberation, he was refused paper and pencil, and in his indomitable artist’s spirit, he forwent his daily bread ration and used it to shape a small squatting female figure.

Fate joined Miriam and Joseph Carlebach and four of their nine children and Erich Brill on the same transport. The people summoned for deportation had to report at the assembly point, the Masonic Lodge of Lower Saxony in Moorweidenstrasse and spend the night there. The following day, December 6, 1941, the train with 756 citizens of Hamburg departed from Hannover station. On its way, it collected further Jews from Bad Oldesloe, Kiel and smaller towns and finally from Danzig, so that the number of deportees finally reached 964. During the three-day journey, Erich Brill was elected spokesman of car 12. At the end, Riga and not Minsk became the destination. The city’s overcrowded ghetto was unable to accommodate the mass of people, so that the new arrivals were taken to the abandoned farm named Jungfernhof, where they were supposed to make a new "homestead” for themselves in the derelict barns and buildings.

From the letter that Erich Brill’s sister received from the surviving Jewish doctor Ludwig Elsässer after the war, the painter’s family learned that Erich had assumed a function as scribe and therefore did not have to suffer so much from the harsh working conditions as others did. In her book Menora und Hakenkreuz ("Menorah and Swastika”), Miriam Gillis-Carlebach recalled that while her husband tried to school the children, the artist Brill taught them how to make snow figures. In spring, women, children and men not fit for work were summoned for the "operation Dunamünde” – they were told they would find easier work and better living condition at a fish-processing plant. On this pretext, 1,600 persons were loaded on trucks on March 26, 1942 and taken to the forest of Bikernieki (now part of the city of Riga), where they were shot. It was the first of a series of mass shootings in that forest; the total number of victims is estimated at 46,000. Thanks to Dr. Elsässer’s testimony, we have Erich Brill’s exact date of death: the bullet of his murderers struck him on March 26, 1942.

His mother succeeded in emigrating and joined her daughter and the daughter’s husband Bruno Tyson in New York City, as did Erich’s sister-in-law and her family from Amsterdam, whereas his brother Fritz Brill suffered a fatal heart attack during their persecution. Erich Brill’s ex-wife Martha (Marte) lived in Sao Paolo until her death in 1969. Erich and Marte’s daughter Alice remained in Brazil with her husband and their three children. Alice Brill Czapski manages her father’s artistic legacy and extensively corresponded with Dr. Maike Bruhns about it. To commemorate Erich Brill’s 100th birthday, his daughter organized an exhibition of his paintings.

Alice Brill Czapski became an artist in her own right, known especially for her photographs that pioneered new paths of vision. On Alice Brill Czapski’s 90th birthday in 2010, Marlen Eckl published a tribute to her under the title Kunst als das wahre Leben ("Art as the Real Life”).

Translated by Peter Hubschmid

Kindly supported by the Hermann Reemtsma Stiftung, Hamburg.

Stand: September 2019

© Inge Grolle

Quellen: 1; 4; 5; 6; 8; 9; StaH. 331-1 II Polizeibehörde II Ablieferung 15 Band (Auskünfte von Ulf Bollmann); StaH 351-11 Amt für Wiedergutmachung _15976, _44076; 363 _EB 57 Senatsakten; Sta Hannover Hann.86 Hameln Acc. 143/90 Nr. 3697 Gefangenenpersonalakte Erich Brill; Sta Hannover Hann. 86 Hameln Acc. 143/90 Nr. 146 Gefangenenkarteikarte; Bruhns, Geflohen aus Deutschland, S. 29f.; Dies., Kunst S.87–90; Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon, Band 14, S. 231; Der neue Rump. Lexikon der Künstler Hamburgs, S. 64f.; Bruhns, Akte Brill, Mail von Maike Bruhns v. 3.3.2014; Brill, Der Schmelztiegel; Gillis-Carlebach, Jedes Kind, S. 177f.; Dies. In: Paul/Gillis-Carlebach (Hrsg.), Menora, S. 558; Brief von Thomas Mann zu dem Roman von Marte Brill, 8.9.1941; Robinsohn, Justiz.

Zur Nummerierung häufig genutzter Quellen siehe Link "Recherche und Quellen."